For many reasons, January brought the reality of climate change crashing down on Australians: there was the record-breaking mean temperature, the horror of the Murray-Darling fish kills, and the Tasmanian bushfires to name just a few.

But while Scott Morrison couldn’t even say the word when visiting the devastated Huon Valley, the group of students he once told to effectively shut up and sit down have been busy turning 2019 into the climate change election.

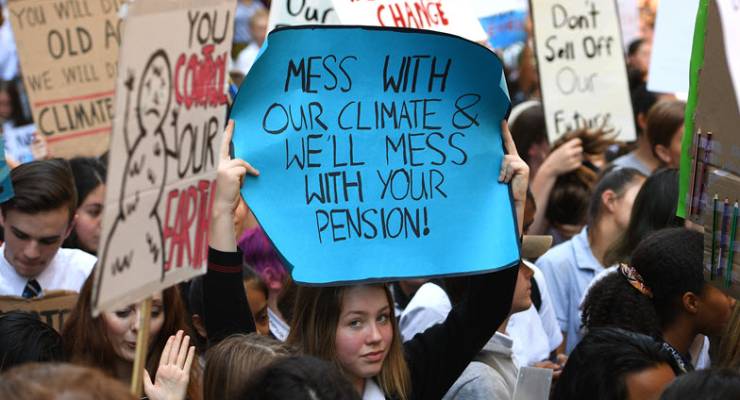

Volunteers at School Strike 4 Climate — which last year grew from one Swedish teenager’s strikes to 15,000 protesters marching across Australia — have started the year by calling unions and politicians, running state-based training courses for new volunteers, running social media campaigns, appearing on Q&A, and organising individual protests (the next one of which is set for tomorrow, so watch out Bill Shorten).

Now, the group has launched plans for its second global walkout on March 15. Hundreds of thousands of students will protest worldwide, and Australian kids will march in 25 sites across Australia. Victorian member of the logistics and press team Anthony James tells Crikey “students do not want to be leaving the classroom, we’d much rather turn up every day and receive the education our families and governments are paying for”. The team also promises, however, this will be the second protest of many.

“As we see currently with the unprecedented flooding in Townsville, the bushfires across the country and the latest heat record set last month, we do not live in a normal period of time,” James says. “Therefore, we do not want or need a normal response from our government. We need them to recognise climate change for what it is — an emergency.”

Citing the IPCC’s recent warning that “we have only 12 years left, to not only act, but have acted”, James lists the group’s two major demands:

- A 100% renewable grid by 2030 (an ambitious but technically viable task)

- A phasing out of coal mining, starting with the Carmichael-Adani mine, and transitioning workers to sustainable industries such as “green economy” gigs or new electric vehicle manufacturing.

These will be difficult for a number of reasons. Firstly, the current government is openly canvassing plans to use taxpayer funds for new coal plants. And, even ignoring the Coalition’s coal fetish, Labor is only calling for 50% renewables by 2030. Despite genuinely promising signs of a regional transition with the announced Gladstone hydrogen hub, Labor has shown no interest in phasing out coal mining and just this week ruled out blocking Adani.

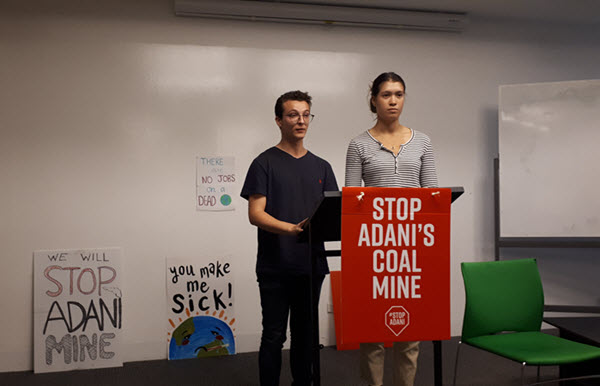

The group has reportedly gained support from the new candidate for Kooyong, the former-Liberal and Clean Energy Finance Corporation chief Oliver Yates, but Victorian coordinator and Year 11 student Siena Koh speaks of considerably less success from a meeting with her current member, federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg.

“So the ex-environment minister, his hands are tied in so many regards…” Koh says. “The things that are said are quite reassuring in some ways, but then at the same time it hasn’t been backed up with action.” While Frydenberg acknowledges that global warming exists, he famously proposed a wet-blanket of an energy policy.

James agrees that “it’s very hard with the federal election coming — every party has their lines sorted and we’re not going to hear anything different until after then”. (He has felt this frustration for awhile, having left the Young Liberals over climate and refugee policies; since he has recently graduated, he is soon stepping back from his leadership role and ultimately intends to go into politics.)

The national School Strike 4 Climate campaign, which is split unto state divisions and backed by members of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition, has however been welcomed by expected allies such as the Greens, independents and, reportedly, local governments, such as Darebin, Central Goldfields Shire and Yarra Council (James notes the latter have not been as curtailed by party politics).

James and Koh tell Crikey they have also had varying levels of support from their schools. Koh describes Methodist Ladies’ College as supportive and active in the environmental space, if impartial in their request for students not to wear school uniforms. James notes his private school did not address the movement at all, and says he did not see a single fellow student at last year’s strike.

The organisers are anticipating the same kind of bizarre backlash from far-right politicians and commentators they faced last year. But, Koh argues, “[they] just proved our point really”. “I haven’t quite had my lesson on how to do mining, as Matt Canavan suggested, but it just shows some of the ineptitude of these politicians and how childlike they are as well — the fact that they’re getting into an argument with a couple thousand students,” James says.

“So, you just sort of go, ‘okay this is basically bullying in the corridors, we’ll let them be. You don’t give the bully the attention’. We’ll focus on what we know is real.”

James and Siena. I’m eighty and am thanking you for your leadership. This is your fight. Don’t delay or lose focus.

Great to see a new generation of politically active kids being born….the time is right for this movement to bloom and get good results.

Shorten will both listen and act; the LNP? Beyond repair sadly….

Will he? You have Bowen spouting the usual garbage about “sovereign risk” in relation to not wanting to block Adani…..so sadly my faith in Labor on this matter is heavily tarnished.

Frustrated students should encourage their older brothers & sisters to vote for a party which believes in climate change. Being underage their hands are tied but they should lobby loudly.

Morrison will send them to the Naughty Corner but Shorten will respond.

I suspect a very large % of the young will already be voting anything but LNP.

‘Bloody foreign entities meddling in our democratic political process!’

About 10 times more intelligence from any single one these students that in the whole of the Coalition.