If you approach Glen Innes from the south, passing through Ben Lomond and Glencoe amidst tall stands of poplar and conifer, you could be forgiven for thinking you were taking the high road through a small patch of Auld Scotland.

It’s midday on a Friday and I slip past the Clansman motel with its triumphant bunting of rampant lions and saltires, cross Mackenzie and Lang streets, looking for somewhere to eat. As I walk there’s a familiar — but unlikely — sound, which only grows louder as I turn onto Grey Street. Outside the town hall, in glengarry and hose, kilt and sporran, stands a lone piper playing what Alec Guinness once called The Tunes of Glory – “Flower of Scotland”, “The Gathering of the Grahams”, “The Black Bear” and all the rest.

I’m on a mission, but if I had the time I wish I could stop and ask, between sets, whether he was doing it for love, for auld Scotch sentiment, or whether the local chamber of commerce thought it might enhance their idea of a commercial Celtic theme park.

There’s a McDonald’s up ahead, and it is only when I step inside that I’m confronted by a reality of life in the economic rationalist paradigm: poverty. Not kids whiling away the hours, either jigging school or killing time before their next Centrelink interview, but real, grinding poverty. Middle-aged poverty. The poverty of people in stubbies and bare feet, people who might have once had jobs and who might have once sunk roots into their own plot of earth.

***

Glen Innes, like so much of regional Australia, seems a throwback to an earlier time when our nation was not only more homogeneous, but was also more inward-looking and yet more socially aware.

40 years ago, it was a proud town of 6000, with a bustling population of working families who earned a few bob through honest work and spent most of it in their own town.

Its population is still hovering around the 6000 mark, in a state that has grown grown over the intervening years from 4.78 million to 7.48 million — an increase of 56% that Glen and most towns like it have missed out on. And beneath these depressing stats lies another Glen.

A special research report on northern New South Wales commissioned by the 1974 Henderson Inquiry into Poverty — they don’t have such inquiries any more — concluded that 25% of households living in dire poverty in the New England region actually had an employed bread-winner; mostly working as fettlers (railway maintenance workers) on the Main Northern Railway which passes through Glen towards the border town of Wallangarra. Yet such employment, modest though it was, still provided sufficient income for railway families to live in detached cottages, many of which they were able to own themselves.

Then in 1988 NSW voters elected the bone-dry Greiner Coalition to government — and one of their first actions was to close the Main Northern Railway north of Tamworth. Perhaps they really believed, as Margaret Thatcher had asserted so stridently in the UK ten years previously, that there would inevitably follow a shaking out of employment from dying industries to those of the future. Or perhaps they didn’t.

In any event, unemployment figures from 1996 tell the true story. The Commonwealth Employment Service measured the unemployment rate in Glen Innes (at a time of economic growth) at 11.3%. And we can believe the integrity of those figures, as they were among the last produced by the CES before it, too, fell under the axe of John Howard’s Thatcherism.

***

The nice thing about poverty is that, as an equal opportunity employer, it doesn’t discriminate. Crumbs brushed from the table of plenty are available to anyone. They’re all there immersed in the palsied pallor of poverty — a grey, hollow-eyed stare of hopelessness.

When I return to Grey Street later, a transformation has occurred; the street is virtually deserted. The piper has packed his bag and headed for the hills, farmers have gone back to the property, the wait staff are wiping down the coffee-shop tables, and the Centrelink recipients lounge around. And it is then that we see Glen Innes as it really is after 40 years of neglect. The last desperate bastion of the battler.

The bookshops, second-hand only, display their stock out hopefully on the street to tempt the passer-by, as do the the clothing shops. But the young bloods on their skateboards, sideswiping dumb tourists like me, aren’t interested in thieving. Even for a cheap thrill. For what is more significant than these brave acts of commercial trust is that there isn’t a single sign of that hallmark of our age — the branded, franchised store. No Katies, no Sportsgirl, no Brumbies, no Bakers Delight. No Optus, no Telstra. No Sanity, no Bras N Things. You name it, it isn’t there.

All that is left in Grey Street are the vestiges of an Australia left far behind in a mad rush to global identity. Instead, we see the family butcher, the family baker, even mum and dad’s fish ‘n’ chip shop, 200 klicks from the sea. Still hanging on. With barely a customer in sight.

***

Perhaps I should have contacted the local council or the local paper or the local chamber of commerce for a comment but I wasn’t brave enough to cop an earful of boosterism that would have earned the envy of Sinclair Lewis’ Babbitt.

I could have contacted the personable Adam Marshall, local state member of parliament and junior minister in the Berejiklian government, and asked: “Why, Adam, is it that you seem unable to demand from your Coalition partners, those arch champions of investment — be it light rail, heavy rail or, sine qua non, stadiums — that they invest a little extra in people, for a change?” But that would be rude.

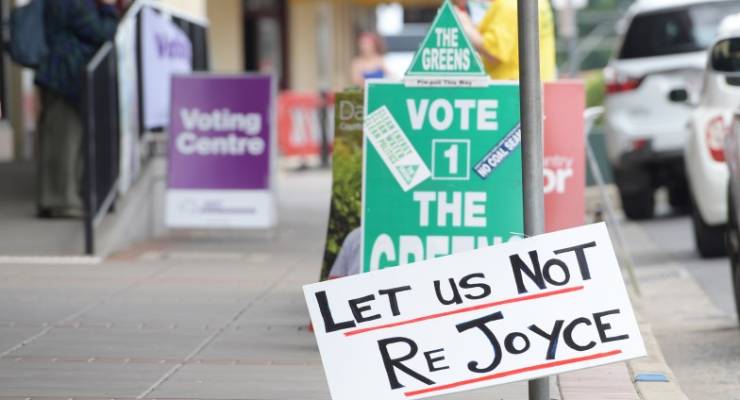

And then I thought of Barnaby Joyce, local federal member and special drought envoy, who had been in Glen recently, sounding-off as ever. I was desperate to ask him why he had a fixation on beef export prices, cotton irrigators on the Barwon and Sarah Hanson-Young? If he’s the drought envoy, what about a cloud-burst of federal dollars onto his own constituents, whose entire lives and well-being appear terminally drought-ravaged?

But then I had serious misgivings. Joyce is such a busy man with important power stations to build in central Queensland, that he might just say, Let’s cut out the middle man and you read this instead, it’ll explain everything — thrusting at me a copy of his recent philippic memoir Weatherboard and Iron.

I quaked at the idea, not so much as wilting before the wit and wisdom of St Barnaby, but rather at the thought of returning to Maccas and suggesting to The Great Unshod still marooned there that they read it.

I didn’t want to be any sort of middle man to be cut out of anything.

I remember coming back from Cambodia for a visit and staying at a mate’s pub in a nice little village in the WA Wheatbelt about 6 years ago. The place had sports teams sponsored by the pub, a neat primary school and pleasant wide streets with tidy houses. It was quiet and clean and safe.

I dreamed of the future when a world class NBN brought new families to the bush. Parents who could work online, medical and educational benefits flowing from ultrafast Internet. Country towns could be reborn and families could live easily in houses on big blocks. Kids could walk to school safely and communities would flourish.

Instead we got nothing good and country towns are dying. Thank you LNP.

An interesting snapshot Rod. You should have talked to young Adam even if Barnyard was a bridge too far. Marshall romped back in a few weeks ago with an increased majority and Joyce will too. I lived and worked in the Northern Tablelands for over thirty years and know Glen and the region well. The people you describe also live in Admidale”the Athens of the north”, Guyra, Tingha, Inverell, Tenterfield, Uralla and all the little whistle stops in between. Did you talk with any of them, you know, relate, find out about them and their lives, not just look. You might have be surprised at what you learnt. A lot of people in these places wouldn’t go to the big smoke if you paid them. That’s not to say they don’t need much better services, infrastructure and opportunity. You also seemed to have missed the large populations of First Nations people all over the area, apparently invisible to you.

Irrelevant. I love my little regional hole too, and am lucky enough to live in one that is still growing both in population and economically. Grew up here and will grow old and die here. But the lack of services compared to the big 3 metro cities is suffocating and makes attracting the sort of people that make a place thrive way harder than it should be. This flows on to everything, most directly robbing the local economy of the spending these people would bring. So much of my high school class went off to study or work in Brisbane etc and never returned. Some of them went on to be highly paid professionals, they don’t live here though.

Meanwhile, the debate around immigration policy of this country, as well as infrastructure and population policies in general, is dominated by 3 cities screaming about being full. Guess they shouldn’t have neglected everywhere else until half the nation moved in with them. Bugged fiscal mechanics, nothing they could do!

If you are referring to Glen Innes in your comment “that is still growing both in population and economically”. If you are talking about Glen Innes that is incorrect. The region is losing population and declining in economy.

The reason professionals won’t come to Glen Innes they soon see it is the town and region of leaderless hopelessness and decline. Glen Innes is a town of extreme toxic culture that pervades across the communty. I love living in Glen Inens, and would never move, but it is truly the town of complete and utter hopelessness and a rotting couldn’t care less community about anything and everything.

Glen Innes is on the road to everywhere going nowhere, Inverell isw on the road to nowhere going everywhere because of leadership and direction and a community that has considerably more care factor.

I remember Glen Innes as a lovely little town and the dearth of “high street shops” sounds perfect to me! We note Maccas hasn’t been backward in building of course. There is a case for government intervention, of course there is… But there is also a case for enterprising people to be innovative and create opportunities! Perhaps they have had the innovation sucked out of them through years of voting in shit politicians!

They still vote overwhelming for the National Party which does nothing for them.

You can’t help people who won’t help themselves.

New England was held by an independent for 12 years. You might have heard of him? Not to mention the indie state member they had from 1999 to 2013. How about their Greens party mayor? But don’t let facts get in the way of looking down on the Peasants.

As noted from the names of the towns, it always puzzled me that the region wasn’t called New Scotland.

It might have been named in the same spirit that Erik the Red named his second discovery Greenland to encourage migrants, Iceland being not a real come-on.

One of the reasons the towns have been gutted is that the land has been so abused over the last century & a half – denuded and hammered by hard hooves so that when the rain falls it just rushes of the hardpan, erodes even more gullies, taking what little topsoil remains.

One day the soil miners, aka ‘farmers’, are going to finally realise that they are not in Europe and use the land appropriately.

For the next couple of decades that will involve massive tree planting and key-lining the paddocks and levelling the dams, aka evaporating pans to allow the land to drink again.