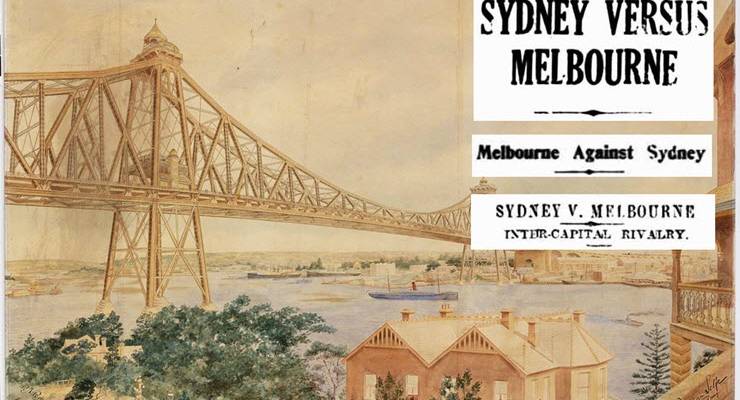

This week Crikey is taking a look at the Sydney/Melbourne rivalry. Is Sydney’s golden age as Australia’s premier city over? Read the other stories here.

It’s an old wound, and it began to weep again following recent reports that Melbourne’s population is set to overtake Sydney’s. But how far back does the Melbourne/Sydney rivalry actually go?

The roots of a rivalry

After the British Imperial Parliament passed the Australian Colonies Governing Act 1850, the newly separate New South Wales encouraged free trade, and only charged tariffs on tobacco, alcohol, sugar, tea and coffee. However, the discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851 led to an influx of wealth and population that dissipated just as quickly a decade later. To keep former miners employed locally, Victoria imposed additional import duties on clothing, millinery and leathergoods; woodenware, furniture and toys; woollen blankets and rugs; and glassware, earthenware and porcelain.

Thus protected, Melbourne’s manufacturing base grew stronger than Sydney’s and the familiar contours of today’s rivalry began to take shape: free-wheeling Sydney as the finance and media capital, and protectionist Melbourne as the fashion and culture capital.

In 1923, a tailor from Melbourne department store Lincoln, Stuart would allege to a neutral party — The Mail of Adelaide — that when it came to menswear, “Sydney is more sporting and American than Melbourne, but Melbourne men are more English in the care and selection of their clothes.”

Melbourne spent the 1860s to 1880s as Australia’s largest, most prosperous city, billing itself as “Marvellous Melbourne” and building grand banks, hotels and coffee palaces. But it didn’t have a sewerage system until 1897. An 1881 issue of Melbourne Punch includes a joke headlined “Our Cologne-ial”: “A new chum coming up the Yarra naturally holds his nose as he inquires: ‘And this is Smell-bourne? I could have guessed as much.’”

In 1889, a northern mole reported archly back to The Sydney Morning Herald that “Malodorous Melbourne” would be a better name. However, Sydney couldn’t really talk: public debate raged there in the 1880s about how to deal with the fragrant brown tides created by raw sewage that emptied directly into the harbour from Fort Macquarie, where the Opera House now sits.

Melbourne’s boom had been built on a property speculation bubble that burst disastrously in 1893. By 1895, a Melbourne house could be rented for £1 a week that would fetch £5 a week in Sydney. Still, Federation was delayed as each city argued it should be the capital of Australia.

Begrudgingly, it was agreed a new nation’s capital would be founded closer to Sydney, but that in the interim, Parliament would sit in Melbourne.

Sydney took this decision badly; and the cities fought over the location of key military bases, and where the governor-general would live. Even in World War I, Sydney complained bitterly that war efforts were based in Melbourne.

Melborn and Sideny

By February 1925, Sydney’s population had reached 1 million; but Melbourne’s population was already much more spread out, occupying an area of 225 square miles within a radius of 10 miles from the GPO, as opposed to Sydney’s geographically confined area of about 185 square miles.

The habit of bragging about — or disputing — the two cities’ respective rankings in “most liveable” indices is only the most recent manifestation of a pitiful tendency to appeal to outsider referees. Royal Navy Lieutenant Charles Richard opined in his 1924 book Round the World with the Battle Cruisers: “of the two cities I must confess a preference for Melbourne; it is cleaner, better planned, and takes life more comfortably”.

And in July 1925, one JD Woodruff, a visiting debater from Oxford University, wrote a light-hearted “sketch” about the rivalry for Sydney’s Sunday Times:

The stranger finds the Sydney people more sensitive, more angry if the harbour is called the river, more anxious to extort praise of their city. The Melbourne people are less sensitive, they are more concerned with the failings of their neighbours, more fully primed with proofs of the greater bigotry of Sydney, more fundamentally complacent.

In 1968 Melbourne folk quintet The Idlers Five released a novelty song, “Melborn and Sideny”, which hit number one… in Melbourne.

Sydney has always lived up to its nickname “Sin City”, from ugly, racialised moral panics to the 1927-1931 razor gangs and the 20th-century ecosystem of official corruption and organised crime. As early as 1907, The Sydney Morning Herald blamed “the disgraceful state of the thoroughfares of Sydney” on jobs-for-mates cronyism among Sydney’s sanitation workers, whereas Melbourne’s council workers were employed systematically and impartially.

The sobriquet “Bleak City”, meanwhile, was popularised by Sydney arts apparatchik Leo Schofield in his Sydney Morning Herald column “Leo at Large” — which caused some southern resentment when Schofield was appointed Melbourne Festival director in 1993. But it was Melbourne transplant David Williamson who kept the rivalry sizzling through the ’80s with his semi-autobiographical 1987 play Emerald City, which has been called “part love letter, part hate mail” to a hedonistic, opportunistic Sydney of hustlers.

Now, Melburnians seem to prosecute the rivalry most vigorously. Indeed, Sydney has being Melbournising over the past 20 years: a term that originally carried resentful connotations (especially in South Australia — but that’s another article!), but now is more likely to longingly evoke city apartments, European-style alfresco dining, small, hip bars, and no lockout laws.

In 2017, Richard Glover tried in vain to interest his ABC Sydney listeners in the fact Melbourne was overtaking Sydney as Australia’s largest city. “The rivalry is over,” he concluded. “Melbourne, you’ve won.”

Do you think Melbourne has won? Do you care about the fight in the first place? Send your comments to boss@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name.

I don’t live in Melbourne or Sydney but in a regional area. The kind of regional area that perplexingly voted for ScMo and his empty-head government in the recent election and returned our talents- waiting-to-be-discovered MP with an increased primary vote, despite several scandals. The kind of regional area that gets next to zero coverage or interest from Crikey. The kind of area with real issues, complex issues-that sway elections. Which is why none of the fine writers and commentators featured in this publication were correctly able to predict what was happening out here, and places like here located well away from the bubble. Heck, the voting patterns in Western Sydney and Melbourne weren’t even picked up by analysts in these pages. It is high time that a publication with the depth of talent that is Crikey, spends just a little bit of time focussed on issues that matter to those of us who live outside the power centres of the major cities. Not just the politics of dumb decisions that effect the regions but which emanate from Canberra or the east cost capitals, but the real issues that affect people’s daily lives. There are lots and lots of them, many rarely if ever faced by city dwellers. Sydney-Melbourne rivalry-well written piece but in the scheme of things, not really a priority for many outside that east coast belt.

And it’s very much from a Melbourne perspective. I think it would be interesting if we got a little from a Sydney perspective?

Great comment and suggestions Free to roam. I also dwell in the regional twilight zone, good to know I’ve got company.

Although I cannot find reference to it on the internet, I recall a comment by a former UK PM, Jim Callaghan, who said that if stood on the balcony of a Sydney hotel, the sound you could hear was that of money rustling.

“After the British Imperial Parliament passed the Australian Colonies Governing Act 1850, the newly separate New South Wales… “. Pardon? The Act provided for increased self-governance by the settler population in the colonies in eastern Australia, but they did not separate from anything. Not sure what you mean?

Hi Bruce, what I meant was that the former colony of New South Wales (having previously been a single colony governed from Sydney) had separated into two colonies, NSW and Victoria.

BruceHassan’s point took me off to google. As far as I can make out, 1850 (UK), 1851 (NSW) and 1855 (Vic) all seem possible candidates for the “actual” legislative moment of separation, with 1850 probably having the weakest case, as BH suggests. Curiously, the NSW records and archives site gives the nod to 1850 – you would think NSW would want to lay full claim to agency in this matter.

As I understand it, the 1850 British act made separations possible and provided a model constitution for any new entities, with Port Philip specifically foreshadowed. In 1851 NSW passed enabling legislation, using the model constitution for the new colony. For the next four years Victoria was governed, under that interim constitution, by a 30 member council, 10 of whom were appointed by Lt Governor La Trobe, who still reported to the NSW Governor. The 30 member council adopted a new, much more democratic constitution in 1854 and the first government elected under that constitution was sworn in in 1855. To complicate the picture, some historians suggest that Port Phillip had begun behaving independently in many aspects from the mid 1840s.

From my reading, at least part of the issue was the communications lag between the UK and the respective change-makers in both Sydney and Melbourne, which meant that the local legislatures took a while to respond to the British change.

Canberra, actually being the nationals capital, won and now is quietly selective in who discovers it from either of these places.

From my humble opinion Sydney’s Harbour & Opera House are peerless, while Melbourne is more progressive. Wasn’t Melbourne the richest city in the world in the 19th century gold rush?