The key to understanding the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation is that it’s not merely about Western civilisation but in favour of it. The fact that it is ‘for’ the cultural inheritance of countries such as ours, rather than just interested in it, makes it distinctive. The fact that respect for our heritage has largely been absent for at least a generation in our premier teaching and academic institutions makes the Ramsay Centre not just timely but necessary. – Former prime minister Tony Abbott, in Quadrant, May 2018

Paul Ramsay left $3 billion to charity when he died five years ago. Yet that remarkable philanthropic gift, then the biggest single donation in Australian history, has been overshadowed by a very public brawl over Ramsay’s estate that has dragged in two former prime ministers, a gaggle of respectable universities and a cacophony of ideologues from both sides of the political spectrum.

How could this have happened to someone who had been at pains to live a quiet life out of the public spotlight?

In a word: money. Because Paul Ramsay left no specific instructions for how his $3 billion estate should be spent, a vacuum was created for numerous friends and associates to step in since his death to interpret what they believe were Ramsay’s final wishes.

The first mention of a new initiative to elevate the status of Western civilisation appeared in an “exclusive” story in The Australian on March 3, 2017. The paper’s well-connected recipient of Liberal Party information, Paul Kelly, revealed that a centre dedicated to Western civilisation would be created using money from Ramsay’s $3 billion estate sitting in the Ramsay Foundation. Kelly described it as the realisation of Ramsay’s “long-held aspiration”. John Howard, who would become the centre’s chairman, was quoted saying the new centre would be “well financed because we are keen to see Paul Ramsay’s wishes are honoured”.

That news created a mild stir, but nothing compared to the furore that followed publication of an article written by Tony Abbott in Quadrant, the conservative ideas magazine, in May 2018. Abbott described how he had duchessed Ramsay over several years to convince him to spend “the bulk of his fortune” to set up an undergraduate scholarship around the theme of Western civilisation. Using Cecil Rhodes as an example, he argued Ramsay could put his money to good use by passing along the values that had underpinned the Catholic upbringing they both experienced — “the New Testament, Shakespeare and British history” — to counter what Abbott described as a curriculum “pervaded by Asian, Indigenous and sustainability perspectives”.

In the article, Abbott says he suggested that the billionaire donate not just some of his money to such a centre but the bulk of his life’s wealth …

“It was with much trepidation that I first made the suggestion that Paul should devote the bulk of his fortune to something like a Rhodes scholarship based here in Australia. At first, Paul had listened with the indulgent humour that he always showed to the more outlandish ideas of his friends. But as time passed, he clearly warmed to the idea of doing something unique and making a difference in the future as well as in the present; of leaving a stand-alone legacy that could change our country for the better rather than simply making other people richer, and already existing institutions even better resourced. After all, if Cecil Rhodes, that other philanthropic bachelor, could help to create generations of ‘men for the world’s fight’, why shouldn’t he?”

So exactly how much money is going to the centre to fertilise thoughts about Western civilisation in Australian universities? INQ understands the foundation has set $25 million a year as an informal benchmark, based on a budget proposed by the centre. But there is apparently no fixed funding allocation and the centre can make a case for more money at any time. According to documents filed with the government charities register, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission (ACNC), it received $5 million in the 18 months to December 2018.

Members of the Ramsay Foundation are reportedly unhappy about the media attention generated by the incessant front-page culture war that has erupted over the centre

Even if the centre costs $25 million a year, this is a relatively small portion of the foundation that holds the bulk of Ramsay’s $3 billion estate, which would be expected to distribute around 5% of its corpus — $150 million — each year. And given its benefactor died without any apparent instruction about the lifespan of the foundation, it may well decide to distribute a lot more than $150 million a year. This arithmetic suggests that, far from Tony Abbott’s desire to see Paul Ramsay give “the bulk of his fortune” to support teachings about Western civilisation, the project will receive less than 20% of that considerable fortune.

So how committed was Paul Ramsay to the centre? Even Abbott admits the idea was his. Ramsay’s unfinished will, leaked to Sydney Morning Herald reporter Jordan Baker, made no mention of such a centre, and members of the foundation are reportedly unhappy about the media attention generated by the incessant front-page culture war that has erupted over the centre, not to mention the stuttering attempts to actually get more than one university to run a Ramsay funded course.

“Obviously the Western civilisation thing has kicked off but who knows whether what eventuated was what he had in mind,” said former Ramsay Foundation head Simon Freeman.

John Howard told INQ that Ramsay had a “strong commitment to the goals of what is now the Ramsay Centre … he wanted The Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation to be founded,” he said in a comment, which goes no further than stating the obvious.

But media stalwart Ray Martin, who described Ramsay as a clearly conservative man with old-fashioned values who enjoyed Australia’s ties to the British crown, believes the billionaire would be disappointed with how the debate around the Centre has played out. “Ramsay was conscious of the fact that he was of another era but he was clearly intellectually able to handle a difference of opinion” he said.

“He’d be upset that his offer of a large amount of money to an institute became such a political issue.”

Under the tutelage of Howard as chairman of its board of directors — a position he was gifted by Paul Ramsay at the company’s 50th anniversary party — the politics of the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation are hard to ignore. Especially in the intensely political and ideas-driven world of Australian universities, in which academic autonomy is regarded as an article of faith.

The centre is currently in negotiations with multiple Australian universities, including the University of Sydney, to fund a new program in Western civilisation. It has just unveiled a new $50 million deal with the University of Queensland to fund 150 undergraduate scholarships and a new course to begin next year. It has also signed an agreement with the University of Wollongong and is in talks to host a Perth summer school at University of Western Australia.

But plenty of universities have knocked the centre back, including ANU and the University of Melbourne. And such is the controversy surrounding the centre that even the mention of Ramsay’s name sparks student protests. All this despite assurances by Simon Haines, the centre’s chief executive and an English literature professor, that “this will be a teaching enterprise, not a political one”.

Abbott’s Quadrant article was toxic for the centre. Its opponents used the essay as evidence of the centre’s political motivations, with some saying it is part of a wider campaign to roll back the more pluralistic definition of national identity that is emerging in today’s multicultural Australia, even comparing the initiative to Howard’s “black armband view of history” views in the 1990s, where he argued that educators gave excessive weight to the Indigenous viewpoint on Australia’s colonisation.

What especially enraged some university leaders was Abbott’s incendiary claim in Quadrant that “every organisation that’s not explicitly right-wing, over time becomes left-wing”.

“There’s no sense that the West is getting slighted in the curriculum,” said Dr David Brophy, a senior lecturer in modern Chinese history at the University of Sydney, and a vocal opponent of the centre. “If anything I’ve felt we need to be pushing in the opposite direction.”

Support for the centre within Ramsay’s inner circle is understood to vary, with board member Tony Clark, a close friend of Howard, believed to be the most enthusiastic.

All of this raises a key question: how strong was Ramsay’s belief in the more conservative Abbott perspective of Liberal Party principles which are now being espoused in the late businessman’s name when he’s no longer alive to defend or explain them?

By all accounts, Ramsay was deeply invested in politics, but his involvement was often at arm’s length. When the Gillard government introduced a means test on Howard’s 30% private health insurance rebate in 2012, Ramsay fought hard from a distance. With the bill set to pass, dozens of staff from his hospitals staged a protest outside the Port Macquarie electorate office of Rob Oakeshott, one of the independent crossbenchers propping up the Gillard government. In a scathing Newcastle Herald opinion piece years later, Oakeshott claimed Ramsay directed his staff to protest, and that TV crews from Prime, a regional broadcaster owned by Ramsay, were tipped off in advance.

A year after the means test was passed, Ramsay’s donations to the Liberal Party spiked. Still, the Oakeshott protest was a rare display from Ramsay. While he poured money into Coalition coffers, he largely left the big ideological pronouncements to the politicians. Money was, in a sense, Ramsay’s way of telling politicians what he wanted. Which makes the very public and protracted culture war over the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation seem so uncharacteristic.

Between 1998 and 2018, Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) data indicates that Ramsay Health Care donated $1.1 million to the Liberal and National parties, and about $180,000 to Labor. Meanwhile, Paul Ramsay Holdings, his personal investment vehicle, gave the Coalition $1.6 million during the same period. Ramsay’s donations often peaked in the lead-up to elections — in the 2011-12 and 2013-14 financial years, he was the Liberal Party’s biggest individual donor.

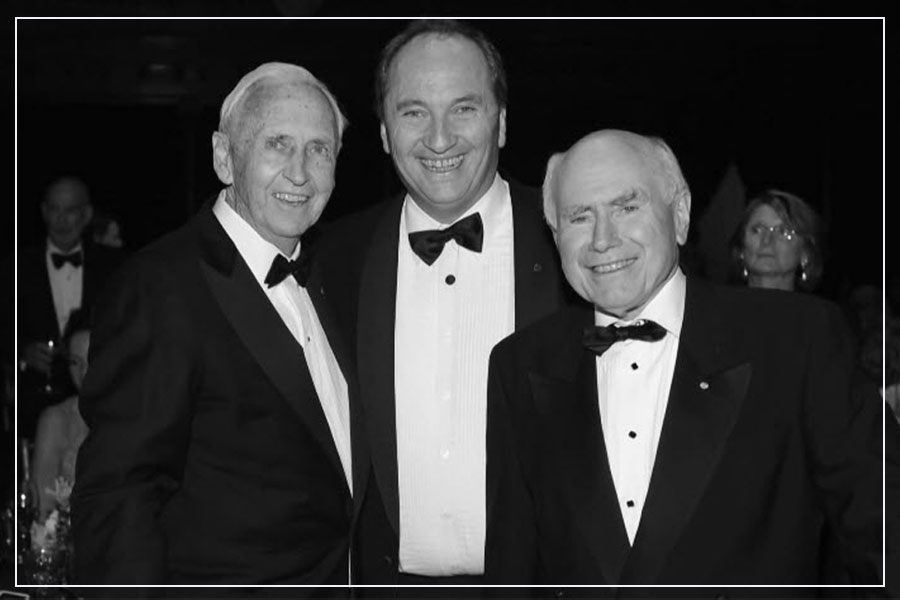

Ramsay’s money helped him buy a seat at Howard’s table. In 2004, Ramsay was one of a select few rich-listers invited to the prime minister’s private barbeque with US president George W Bush. When Howard celebrated his 10 years in office with glitzy dinners in Sydney and Parliament House, valued at up to $10,000 a head, Ramsay was one of the few to get a coveted seat at both events (300 of his fellow silvertails were left stranded on a waiting list).

But politics always sits uncomfortably alongside philanthropy, especially when both are attached to the same person’s name. In the years following his death, the Ramsay Foundation, which has control of the full $3 billion Ramsay fortune, has actively distanced itself from the Centre of Western Civilisation, intent on establishing itself as a politically neutral charity focused on “identifying the root causes of disadvantage”. But not even it is safe from the toxicity that can come with large amounts of money.

The foundation has rapidly expanded to include new board members, all with their own ideas about how the money should be spent. But just like Ramsay himself, the Foundation seems to prefer to keep an opaque veil over its operations. Board members Siddle, Clark and Evans knocked back INQ’s request for interviews via PR gun-for-hire Sue Cato, and the organisation has refused to release the full details of where $200 million grants have been spent since 2015, instead categorising them broadly into key funding areas such as early childhood education and chronic illness health research.

While he was alive, the odd scandal circled Ramsay, but never quite landed. However, after his death, they seemed to stick to him like glue. As debate over the Western Civilisation centre has raged, a woman has come forward claiming she is Paul Ramsay’s long lost granddaughter.

Carlie Ramsay, who was born Carlie Alisa Streeter but changed her name to Carlie Alisa Ramsay in June 2018, claims Ramsay had a relationship with her grandmother when they were young, which resulted in the birth of her father in 1961. Her father, Paul Streeter, was murdered in his Miranda home in August 2015.

“When my grandmother was dying of cancer in 2013, that’s when she told me who my biological grandfather was,” she told INQ. “I just want the truth to come out and I’d like to be recognised as his granddaughter.”

Carlie believes she is the rightful recipient of the entire $3.3 billion endowment to the Ramsay Foundation. She is currently seeking DNA evidence from his estate to prove she is related to the late healthcare baron, and has made an unsuccessful attempt to get on the Ramsay Health Care board.

“It’s not just about money, it’s about finally being acknowledged and continuing the work he’s done and ensuring that his businesses are run based on the values he built them on,” she said.

In life, much of Ramsay’s world appeared to be carefully stage-managed. But beneath the well-cultivated charm lie rumours, unfinished stories and contradictions. Of Ramsay’s many faces, what friends and colleagues remember was his old-fashionedness. He remained private until the very end (rumours swirled about his sexuality), and mostly filled his inner circle with men from the same school, St Ignatius’ College Riverview.

Ray Martin describes visiting Ramsay’s mansion in NSW’s southern highlands as walking through a bygone era: a world of Packers and Fairfaxes, both establishment families with sprawling properties in the district. In that world, a rose-tinted look at Western civilisation might not have seemed so controversial, but shouting academics and ferocious ideological op-eds about one’s legacy is unlikely to be viewed as acceptable southern highlands form.

But then Paul Ramsay died, and the world passed him by.

NEXT IN THE SERIES: ‘He was more like the local priest than the local megalomaniacal billionaire’

Good information here re the background of the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation. Tony Abbott strikes again!

Consider that Kenneth Clark’s “Civilisation” was recast of late as “Civilisations”. The world moves on, but some minds stay behind.