Very few of us will go more than a day or two without having to engage with one of the monopolies locking down Australian markets. They’re so ubiquitous that it’s sometimes easy to forget that most of your money is going through at least one of them.

Luckily, Crikey is here to help. Think of this as a field guide to wild birds — if the wild birds are the enormous, carnivorous type, and you have nowhere to run while they are swooping right at you.

Airports

Perhaps the most monopolistic of all the private businesses in Australia is the airport. In its vast architectural chambers and on its long moving walkways you are a tiny speck, but your contribution to the bottom line is huge.

Airports fall into the realm of natural monopolies. There is rarely reason to build more than one in any city, and so what control is exercised over pricing must come from the rigours of regulation rather than the rather more vigorous rigours of competition.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has a rather limited role in regulating airports, mostly monitoring and reporting prices rather than directly regulating them. That light touch has been much debated, and it leaves us at the mercy of the market.

Sydney airport is a public company, which permits us to get a glimpse of its financial situation. What we see is a company with margins others dare not dream of. Sydney Airport Group made $1.6 billion in revenue in 2018, while operating expenses were around $300 million. After taking into account depreciation, amortisation, finance costs, sundries and income tax, it still reported profit of $371 million.

Airlines have the option to avoid the aeronautical fees at an airport by flying to another city instead. But passengers? We are basically stuck with one airport. Knowing that, airports make hundreds of millions of dollars on retail, car rental, parking and other costs that are all passed onto us via higher prices from the businesses that operate in an airport’s orbit.

Consumer advice: vote for high-speed rail.

Banks

Although not a true monopoly, the fearsome foursome that dominate the Australian financial scene nevertheless operate in a highly regulated space with considerable barriers to entry and substantial economies of scale.

That insulation from competition is one reason big four profits are so incredibly healthy — a combined $29 billion in the last reported year. It’s also one reason you might need a royal commission to shake them out. The normal winnowing of bad providers you’d find in a fiercely competitive sector is absent.

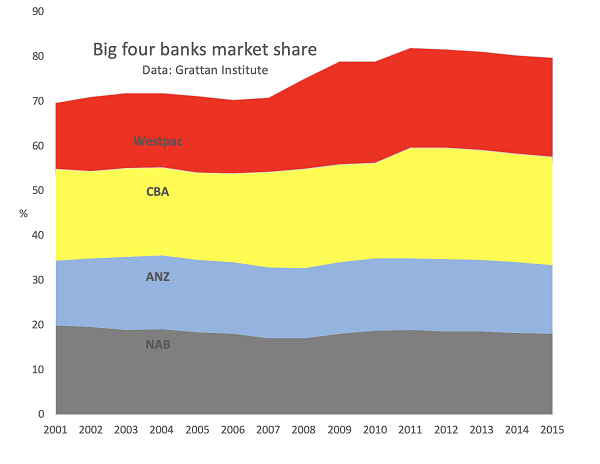

What’s more, the big banks have gotten bigger. During the global financial crisis, a set of mergers increased what they call market concentration. That’s a measure of how much of the market is controlled by the top few firms. As the next graph shows, market concentration in banks grew around the GFC, which is when Bankwest was subsumed into CBA, and St George into Westpac.

Consumer advice: Bitcoin! (Not really, the whole point of these markets is that they’re awfully hard to escape with any sensible option.)

Supermarkets

The market concentration of Aussie grocery retailers is the stuff of legend: two great houses, Coles and Woolworths. Ostensibly these fierce rivals are locked in bitter struggle but neither takes much in the way of damage.

So far as consumer expenditure goes, this is the market that matters most. A huge chunk of our money flows through their annual reports. And many Australians have no alternative but to choose between “The Fresh Food People” and the place where “Good Things are Happening”.

It has been extremely tricky to avoid these two. I use two local independent supermarkets and regularly go to Aldi, but the lion’s share of my grocery spending is still at Woolworths. That said, the impact of Aldi on the big supermarkets has been notable. As of 2018 Aldi had an 11% market share and, unlike banks, market concentration of the biggest supermarkets is declining.

However, over time you may have noticed Aldi heading upmarket, with fewer keen discounts and a higher focus on quality. In parallel, the supermarkets have moved away from “down, down” promotional campaigns and dollar milk.

It’s a reminder that three is not truly a crowd, and that one new firm does not a competitive market make. We can still have an oligopoly with Aldi on the scene. In the US, market share of the top three supermarket is 37%. In Australia, it’s 82%.

Consumer advice: check out Costco and hope that when the German hypermarket Kaufland lands here next year it sets the cat among the pigeons.

Centrelink

This one deserves special mention because it’s not a company, it’s a government service. But it is like a monopoly in that it is a lone provider with no competition, and its performance is beyond appalling.

Centrelink doesn’t make its customers pay for its market power with high prices, but with glacial pace and Olympic-level incompetence. Centrelink’s burden falls directly on those with the least capacity to manage it. The trauma resulting from false robo-debt notices shows us just how negative a badly run human services provider can be.

Consumer advice: the tax office provides a handy front-end that makes dealing with it relatively easy. The issue is not that government can’t provide good service, but that it sometimes chooses not to. Vote wisely.

Supermarkets are not so much of a monopoly. In Perth a family company with farms and orchards has grown its fresh food retail outlets, mostly huge Bunnings-like warehouses from one outlet to 14 while making tidy profits. Their motto, “We grow it. We sell it. You save” mostly holds true and the stores are very popular.

Airports are different. I just flew home to Perth from Melbourne on Qantas. Unfortunately I had to use the toilet while waiting to board. The male toilet was the grimiest I’ve seen in an airport anywhere for many years, it stank of urine and the toilet seat was broken.

Centrelink has been set up by the Coalition Govt to contract our its functions to contract firms with one main KPI – pay out as little as possible no matter if this is by by foul means. They have diddled me put of $6000 in aged pension by arbitrarily over-valuing the rooms in my residence that I rent out, instead of fairly assessing the income I earn from rental. First they tried to pay no pension at all by concocting a figure that was double my assets! After 15 phone conversations (1-2 hours with wait time) they changed this. Then as I continued to challenge their still unfair assessment they have just arbitrarily increased their value of the part of my house that I rent out without any proper valuation, decreasing my pension again. Their tactics are nasty and they pay shady contractors to do it.

That graph shows 30% of the market in banking is not big 4 controlled, maybe suggest some of those? There are heaps of them and you could use their services instead. Probably better advice than a joke about bitcoin?

Is half of this report missing ? Not a word about about the great utilities functional monopolies. Telcos, water, gas and electricity. Along with the mentioned airports the common feature is that they’re all privatised entities of former publicly owned assets. Uncompetitive with rules written by the assets’ buyers.

As for banks and supermarkets there’s a difference between lack of competition and consumer reluctance to access it. I’ve long included a visit to a large supermarket in most countries I visit. It gives a good overview of costs of living, what people actually buy and value and provides a basis for comparison with here. The duopoly here are remarkably good for price and especially quality and range which surprised me. There’s plenty of competition for expensive financial services like mortgages but you have to do the work yourself. Never use a broker.

The monopolies in private health services and insurance and aged care deserve an honourable mention. Keating’s sale of the Commonwealth Bank and Cormann flogging Medibank Private are for me a couple of the most egregious sales of public assets and there are many more. Won’t the great god, market forces always ensure the customer will get the best service at the best price?