This Inq article was published in 2019. Crikey is revisiting it in light of George Christensen’s decision not to contest his seat in the next election.

About halfway through my 71-minute phone call with George Christensen last Wednesday, I asked him whether he had set a date for his wedding to his fiance April Asuncion.

There was a wry laugh, and a pause. “Today,” he told me.

Wait, what? Today he set a date, or today he got married?

“Just been married,” he said, “… and I’m having to talk to journalists about matters that have been brought up in the media and rehashed and rehashed and rehashed.”

He’d emailed me an hour earlier, saying people had told him I’d been asking around about him and claiming “I haven’t had a single call or request from you or anyone else from Crikey“.

That is incorrect, I’d replied. I had called and emailed his office in June requesting an interview, which was declined. (Christensen later conceded that he had been advised of that request.) I had again called that Wednesday, and was told by his media adviser that he was in “back-to-back meetings” (nuptials, it now seems). I had then emailed some questions to the adviser, which I then also forwarded to Christensen. Shortly thereafter, my phone rang.

Christensen was right about one thing — much of what we were discussing regarding his travel to south-east Asia, and the related inquiries by the Australian Federal Police (AFP), has been rehashed. But that’s because of the unanswered questions and curious details that keep emerging and keep the story alive.

Is it a conspiracy? Is he a victim? This is either the most disgraceful, unfair political smear campaign in Australian history, or a bizarre cover-up. Or maybe, it’s something in between.

And even after he called me at 8.13pm on his wedding night to answer questions about it, I’m not sure I was any closer to the truth.

To recap: just before Christmas last year, the Herald Sun broke a story about a federal MP whose travel to “seedy neighbourhoods” in south-east Asia had been “scrutinised” by the AFP after a “government financial intelligence agency” noticed he had been sending money to multiple accounts in the region. According to the report, the AFP had also received a “later alert” from a senior Labor MP, who “thought it necessary to pass on information after being privately contacted by an embassy official, amid concerns within Australia’s diplomatic ranks”. The report claimed the feds had found “no evidence of criminality”, but that the AFP’s inquiries were hampered by “encrypted messages” and that they remained concerned the MP “could still be a target for compromise by foreign interests”.

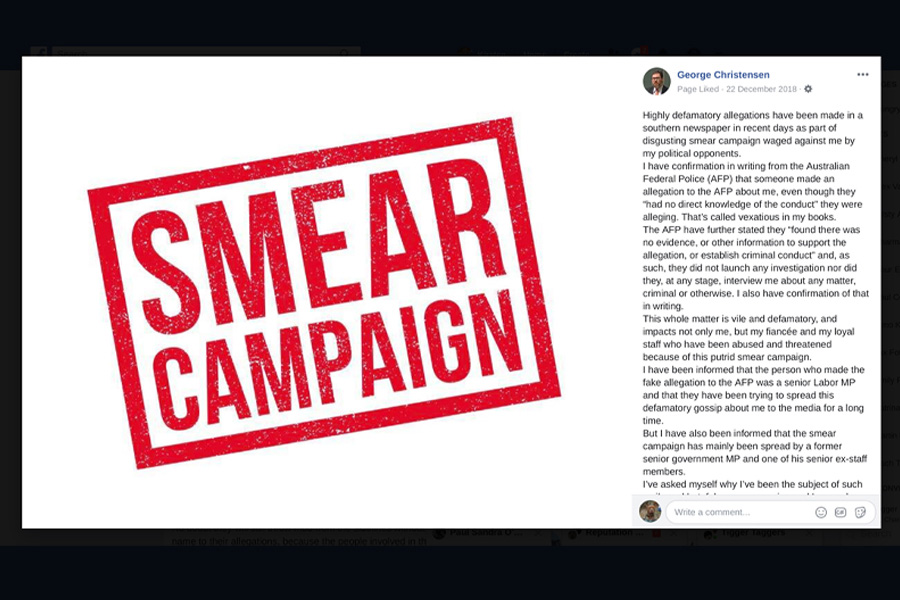

The story didn’t name George Christensen, but the member for Dawson in north Queensland quickly outed himself as the subject on his own Facebook page.

He had little choice. His name was already trending on Twitter, and Reddit was crawling with it. The careful wording of the Herald Sun’s article was being parsed with libellous glee by #auspol punters.

On Facebook and in The Courier-Mail in the days that followed, Christensen went on the front foot to fight what he called a “vile and hateful” smear campaign.

His version of events went like this: a senior Labor MP made a “fake allegation” to the AFP. The AFP concluded there was “no evidence” of criminal wrongdoing. (During our call, Christensen claimed the AFP told him they’d “read the riot act” to the person who’d brought the allegation for “bringing such a story to the AFP without anything to back it up”. Inq asked the AFP about this claim; the AFP declined to comment.)

Christensen said he regularly travelled to the Philippines to do charity and church work, and to visit his fiance April Asuncion, from Quezon City, and her family. He said he sent money to his fiance, who worked in her family’s convenience store, every month. The AFP had confirmed to him in writing that their “assessment was not triggered by a referral from a government agency”, and “inquiries were not inhibited due to an inability to access encrypted messages” he had sent online.

But Christensen didn’t address the heart of the story: that police had warned the highest levels of government that he could be exposed to blackmail. This, he claimed on Facebook, was all a smear campaign being spread by Labor and enemies within his own party. (It soon became clear he was referring to former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull’s office, but a Turnbull spokesman at the time said this was “rubbish”.) Anyone who tried to defame him further would hear from his lawyers, said Christensen. End. Of. Story.

Except a few months later, in the midst of the federal election campaign, the plot thickened:

The Herald Sun obtained and reported on travel records — including dates and flight numbers — which showed Christensen had traveled to the Philippines 28 times since 2014. The records showed the “Member for Manila” had spent 294 days there in just over four years, according to the Hun.

Christensen didn’t directly dispute — or confirm — those details. Instead, he reportedly wondered “how anyone can get their hands on a list like that”.

During our call, I explained to Christensen that this is one of the key questions that keeps the story alive — that if he could better explain what he was doing there for 294 days, this all might go away.

His reply? He was “flying over to the Philippines to see a gal I was involved with. I flew over there numerous times in a single year — I open myself to that accusation — so that’s what happened”.

But Christensen says he met that gal, now his wife, in “early 2017”. The travel records begin in 2014. How does he explain the 19 previous trips?

“I’ve seen dates that have been put out there and I just shake my head at them”, he said. I ask repeatedly whether he’s saying they are wrong:

Me: Are you saying the number of trips is wrong?

Christensen: It’s already been reported — 292 days — it’s been reported.

Me: Are you saying it’s wrong?

Christensen: I’m saying it’s already been reported.

Christensen suggests the travel documents were “doctored” and that they could only have come from the AFP, or Home Affairs, or Philippine Immigration, and are potentially falsified.

OK, so if someone has duped journalists with faked documents, why not just say so?

“There’s nothing I can show to disprove a story — it’s like saying ‘did you beat your wife’,” he told me.

Only in this case, I pointed out, it’s like there are photographs of you beating your wife, and you’re saying the photographs are fake, but you won’t provide an alibi.

Do you have a story tip for Inq? Get in touch via our encrypted tip line.

Crikey encourages robust conversations on our website. However, we’re a small team, so sometimes we have to reluctantly turn comments off due to legal risk. Thanks for your understanding and in the meantime, have a read of our moderation guidelines.