To my poor destructed country

Xavier Herbert, dedication, Poor Fellow My Country

Well, whatever else the Morrison government falls short on, you can’t fault them on their appetite for political warfare.

Under cover of the coronavirus emergency, they have performed a coup de grace on Australia’s universities, film and TV industries, and arts and cultural sector.

It’s death by a thousand cuts, by making no cuts at all — simply letting these sectors twist in the wind as the lockdown ravages social life.

The substantial universities-as-export industry sector has been allowed to collapse, with the rules on JobKeeper being changed multiple times every time a university found a way to access it.

Big screen got its birthday wish of a “suspension” of local content screen production rules; “higher” arts and culture was squeezed out of job support due to substantial casualisation, and no specific help was offered to any but the most mainstream institutions.

This is pretty brutal, but not unexpected.

Far from being a sudden strike out of the blue, it’s a culmination of a war the Coalition has been waging on these sectors since 1996, and one they are now clearly winning.

This is not merely a political-cultural war against the social bases of the Coalition’s class enemies, the cultural side of the knowledge class.

It is a largely successful attack on a certain idea of what Australia might be, or could have been, one going back all the way to the 1880s, but most proximately in the Whitlam era.

That was the idea that we might take our small size by population and our peripheral position in the world as a moment to yoke the state to progressive, even radical, national cultural development, in the manner of a European social democracy.

There was a bipartisan commitment to that from the ’60s onwards. It held to the end of the Hawke-Keating period and limped into the 21st century, before the shifts in the class structure of Australian society made culture wars as important as political-economic wars.

In the post-2013 period, a steady and relentless assault on grassroots arts and culture funding began and a strangling of what remained of the humanities.

The intent was clear: in order to make it easier for the Coalition to hold power, and for Murdoch and the networks to have their say, we were going to become a big dumb country again, swamped by the new global cultural forces made possible by full globalisation, chipping off bits of the country, shipping it north and using the proceeds to pay for Netflix.

That’s the simple story, anyway. The reality is more complex.

That radical/critical cultural-nationalist period only lasted for about 20 years, from its moderate beginnings under the accession of Harold Holt, to the John Dawkins turn in higher education in the second and third Hawke governments.

There had been a genuine commitment to building an intellectually autonomous universities system, with large and healthy humanities departments, to well-funded artistic and cultural production, a local film and TV industry, and much more.

And it worked, not merely quantitatively, but qualitatively. We did build a local publishing sector that eventually threw off the shackles of UK dominance; a film industry that produced a unique run of movies, drawing on European art cinema, but distinctively of this place; art schools worth the name; theatre that didn’t want to make you throw up in the foyer; humanities departments which launched new thinking into the world.

But those 20 years were only a first instalment. To overcome our low population base, cultural underdevelopment and sheer backwardness it needed decades more.

Decades more of steady and plentiful funding (peanuts compared to any other sector) which separated creation not only from market demands but from cultural policy demands. One needed a sector which guaranteed the artist not studio or desk space, but head space, the freedom for creative thought to move where it will.

That’s exactly what we didn’t get. Sadly, the roots of Australia’s cultural self-destruction lie not in the Howard era, but in the Hawke/Keating period, when the universities were yoked to simplistic notions of national development, and the culture industries to national identity and branding.

The relationship between a general and thorough humanities education and cultural creation was lost. Arts faculties became course supermarkets, under pressure of new funding models; creative schools swung towards the market and the multiplex.

Some of this was the product of massive global forces, as post cold-war neoliberalism remade the world. But that was the point at which we needed the creative and intellectual autonomy of culture to be buttressed and maintained.

Instead Paul Keating, trumpeting support for cultural nationalism, corporatised the universities and focused on reproduction furniture-style bourgeois high culture, concert pianists, opera and a couple of superstars.

Done at the same time as the lifeworlds of many were eviscerated by the end of “the Australian settlement”, it destroyed the cross-social alliance which the Whitlam push had built between the labour movement, and our then-tiny arts sector.

Culture became the discourse of the elites and all John Howard had to do was let it decline further.

When the Australian economy had become thoroughly reorganised by the global knowledge economy, what returned as “high” culture was simply the mass culture of the knowledge class, rendered in a distinct middle class mode.

The process of handing out grants — deliberately simplified and artist-oriented in the ’70s — had become a corporate benchmarking, KPI-bullshit exercise, out of which arose the corporatised arts hub and a network of arts administrators boosting each others salaries.

The ’70s had seen the rejection of a prize-based system by people who called themselves “cultural workers”.

Now, the prizes proliferate. Australian writers especially have become a crowd of pick-me bitches, scrambling over each other for the next validating bauble (ha, self included, dont @ me).

Despite years of being shellacked, the sector has been too atomised, self-satisfied and laced into its power as a parallel social elite to mount a real challenge, which would reconnect with broader Australia and make the Coalition think twice about attacking it. (The universities are worse. What do you call 200 Marxists who can’t organise a strike? An arts faculty.)

So yeah, for all these reasons and more, something was running down steadily. The virus had given the Coalition the chance to attack a sector so frail, it can now be strangled in a bathtub. Perhaps out of this, actual collective cultural resistance might arise. A simpler model of creativity would help.

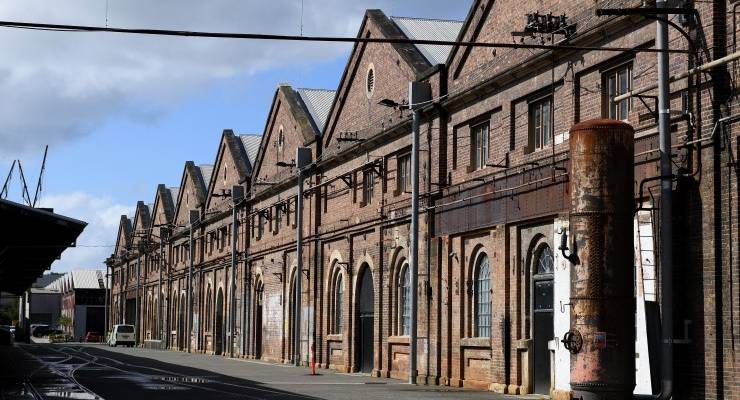

Take Carriageworks for example. How did Carriageworks go broke? It’s a brick shed! Carve it into studios and small low tech auditoriums and theatres, run it with a building manager and a small maintenance staff, and award the studios, etc, rent free to artists, writers and groups.

Needs a building manager and a maintenance staff and that’s it. Peanuts, and every possibility that better art would come out of it.

But that said, ehhhh, the country missed its chance. There is no great cultural shift in peripheral states, without an enabling state behind it. ScoMo’s war on it is just the last cut.

We live on Dumb Street now. Makes you wanna weep. Poor fellow, my country.

What can Australia do to revive the arts? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication in Crikey’s new Your Say section.

The history of the Arts not being courtesan lap dog prostituted hirelings to power & wealth is pretty thin on the ground ..but at least, rarely ,some of it ,has given delightful, insightful, entertaining wall paper points of existential views, to the cave.. So, on the shifting rock bottom sifting sands, of always already these times ,may the ooby dooby doo doodler dabblers’ continue .

I remember when the Howard government came in and – amongst other things – shut down the Button scheme that was making some headway with getting local industries and talent upskilled by multinationals seeking government contracts. Pockets of excellence were quickly squeezed out by a government sold on the idea of the Yanks providing all the brain power and innovation we would ever need, just as they had allowed our film industry and public transport sectors to be shuttered in decades’ past when the USA company men came a calling.

I worked overseas for a period after that with so many Australians (around 2000, over 1 million Aussies were living and working overseas according to a government report) unable to sell their skills into a dumbed down economy. Every so often a ning-nong from Howard’s cabinet would pass through wanting to talk to expats. The only transcript that I can provide is a page of …

Almost 1200 words to claim that the yartz must be allowed freedom from market demand – aka someone wanting what is produced – for creative thought to move where it will, never mind how reductive & irrelevant.

It’s a new Dawn and maybe artistes will learn that someone has to provide the bread otherwise they’ll have to do the traditional starving in a garret before their massive contribution to the common good is recognised.

…or we might realise that culture has its own intrinsic value and fund it because of the beauty and insight it produces.

…and pigs might fly.

Imagine all those “market driven” billions of subsidies paid to LNP fossil fuel donors and mates being directed instead into the arts and this country’s culture.

But… instead we’ll subsidise our own fossil fuel driven destruction while the only people able to apply the mirror of cultural self-perception… starve in their “garrets” and prisons.

Enjoy your “market driven” new world… for how long it lasts.

IMO – Art is often as boring and predicable today as it always has been – but I still think it should be well funded.

What any of us think about art and books has nothing to do with whether a filthy rich mining camp should be funding the arts and humanities.

Ironically, most people who do arts – both creative or humanities – go on to lead very profitable lives.

How unAustralian. The working poor don’t need diversions and distractions from their grind … that’s what sports is for.

What’s wrong with alt-right neoliberals limiting and dictating how we spend our spare time?

It certainly explains the number of grifters and parasites in that sphere.

Very Jeremy Delacy – not that he ended well.

Does the government really hate the arts or do they just hate everything which does not align with their interests?