A web of red ink is spilling out across Australia, dormant but deadly. Companies that would normally have gone broke are instead operating, taking on debts they will never be able to pay back.

“Anybody you’re doing business with might be broke and you just don’t know it,” says John Winter, CEO of the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association.

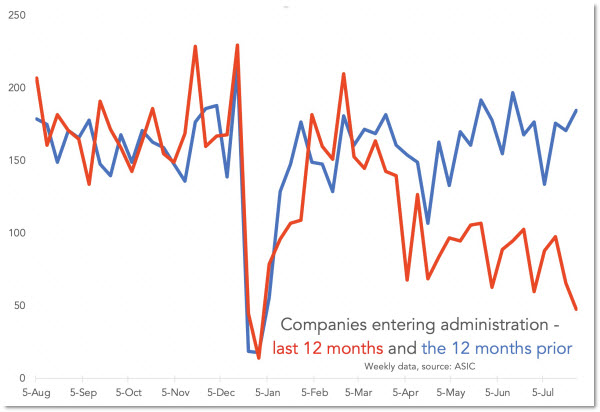

As the next graph shows, the number of companies that have gone broke this year in Australia is well below the historic norm. That is decidedly not because the economy is flourishing. Instead it is due to law changes — changes designed to prevent catastrophic collapse but which are now turning corrosive.

In March, the government changed the laws around companies going broke:

- Previously, if a company owed you $2000 and wasn’t paying, you could make a statutory demand to have the bill paid, and if they did not pay, that company was wound up. Now the limit is $20,000

- Previously companies had 21 days to respond to a statutory demand for debt. Now they can wait six months

- Previously if you were the director of a company that continued trading while insolvent, you faced personal liability. Now you do not.

The point of these policy changes was to make sure good companies didn’t die because of a temporary hit to cashflow. But it has had a substantial side effect. There are dead companies walking. And when they go down they could take good companies with them, says Winter.

“The real issue … is if those businesses are still trading, they are racking up more debt, that debt is owed to other people — to other businesses — and when they finally fall over there will be even less for those creditors which has the snowball effect, it takes those other creditors down as well,” Winter said. “It is not even kicking the tin down the road, it’s creating a snowball.”

Earlier this year, the head of the corporate regulator said there would be too few liquidators in Australia to cope with the incoming surge of insolvencies.

Business runs on a network of “trade credit” — suppliers give them 30 days to pay their invoices. This delay in paying helps with cashflow in normal times. Offering trade credit is also good for suppliers — offering generous payment terms can help them win business without lowering prices, says Nicks Pilavidis, CEO of the Australian Institute of Credit Management.

“Small businesses are really powered by trade credit because they are able to obtain stock and supplies and equipment on extended payment terms and they don’t pay interest or charges for it,” said Pilavidis.

When businesses go broke, trade creditors usually don’t get paid. Bank loans are the priority for repayment, because they count as “secured debt”. Suppliers count as unsecured creditors, and according to ASIC data they can expect to get back less than 11 cents in every dollar they are owed. Businesses can insure that trade credit, but not all do. In a sign of what may be to come, earlier this year insurer QBE announced it would stop writing trade credit policies. It partially reversed the decision after an outcry.

Brad Walter of data company Equifax warns that companies exposed to a business that fails “are going to hurt”.

His firm’s data shows payment times are blowing out.

“There has in fact been quite a significant increase in days beyond terms since March,” Mr Walters said, referring to delayed payment of invoices.

“We’ve seen that across all the states, Victoria in particular but right across the country. And we see that especially in some of the segments like arts and recreation.”

The flashpoint is coming soon.

In September, eligibility for JobKeeper gets tightened and bank loan deferrals cease for many. That’s when company collapses will pick up. The Australian Bureau of Statistics surveyed businesses in mid-July on how they expect to cope when those supports are removed. Of 1000 businesses surveyed, 10% said they would simply close. There are 2.4 million businesses in Australia, so if the survey is right, that would be 240,000 closures.

Not every business that closes involves unpaid debts, but law changes in 2020 mean more business than usual may leave unpaid bills behind them.

> Previously if you were the director of a company that continued trading while insolvent,

> you faced personal liability. Now you do not.

Fascinating. Talk about grey squirrels being introduced into England and their pathogens wiping out the red squirrels. Director liability for operating an insolvent company bought a sense of ethics into corporate life. Now, we’re back to square one; side effects do you say Jason? I’m not sure that the consequences can be altogether envisaged.

We will see how it looks post September for the economy generally. On the positive side, the penny will drop in time. All the pandering to those with excessive ACE2 receptors and an ‘A’ blood type will come to an end if only because they were going to die anyway.

The NT is entertaining isolation for another 18 months or so and from news com au there is from VIC : “Brett Sutton [the State Health Officer – my edit] also confirmed it was suppression, rather than elimination and it could be a battle that lasts for years”.

Yet some States are going to do better than others so long as they remain isolated in terms of movement of people rather than goods. All for a few hundred deaths. A sense of proportion anyone?

Anyone reading up on how to become Amish?

All for a few hundred deaths – that’s the number we get with the lockdowns, the numbers without the lockdowns are your spurious 20,000, and could just as easily go to 250,000, at 1% of the population.

All for a few hundred deaths – yes Erasmus, all for that. What else would we be saving? There are no economic benefits in not locking down, and apart from Melbourne there is basically freedom of movement, so the case for not locking down is threadbare, at best, and tilts towards the delusional.

It it is about context DB. I posted two items to Schwab’s “How lethal is COVID-19? …” last evening. One post concerned the announcement of a vaccine by Putin and the other referred to the ‘Stage 3’ lock-down of Auckland. As to the latter I was pissed on (I think even by you – apologies if I’m incorrect on this point) for even inferring what can be found in any damned text on Epidemiology – as to the (prolonged) dormancy of viruses. However the eradication brigade “believed” (that word again) that NZ was “all good”. We will see what happens.

We have discussed that number that you quoted and as the matter stands (the entire saga has been running only 7 months or so) that is an upper bound over a number of years. As I mentioned in my post regarding the vaccine announced in Russia, the effects of the virus need to be taken into context with that of the flu virus of 1918-19, cancer, pneumonia, upper respiratory flu and TB (ok a bacterium) along with road deaths and dying in one’s sleep. All are a LOT more lethal than the virus effecting covid-19.

As to this article (by Murphy) I don’t like the conclusion any more than you do. That (as some have inferred) a business can merely recommence operations just isn’t the case otherwise we could all have been millionaires back in December. Murphy’s article has a touch of realism about it although it could have mentioned the attrition of businesses by geometric progression (that I have explained).

Compared to the social support that was available (remarked upon by Jackie French) a hundred years ago the knee-jerking is clearly one of over-reaction, to say the least, this time about. It is clear, merely upon the review of the characteristics of viruses, there can be no “free lunch” DB. Agreed that there is a cost “either way” but the assumption that no lock-down = ‘end of the world’ is absurd.

It is going to be a long game. As I have pointed out to Rundell the media obsession with the short term is obscuring the effects of the long term and it is the long term (doff hat to Keynes) that is going to matter.

We should be looking at Taiwan rather than New Zealand to see how Covid-19 should be managed. Their last ‘locally acquired’ case was 2nd April. A total of 7 deaths – 23 million population. Business as usual and Covid-19 is no more of an issue (internally) than the flu. I am not a ‘medical person’ but perhaps it is too late for Victoria to aspire to this? Surely the ‘lucky states’ at least should follow Taiwan’s lead?

The pigeons will come home eventually and we’re here for the long hall.

Taiwan, for reasons that ought to be obvious, is almost self sufficient in everything whereas, for NZ, they are ok for milk, cheese and fish ‘n chips but that it about it. NZ cannot afford NOT to trade (import if one prefers) AND THAT is the difference.

The government is NZ is reacting; it only LOOKS like managing but its actually dithering and this cycle will not be the last (if only for the necessary imports). More to follow next week.

The golden rule “Always watch the hand that isn’t doing the trick” applies.

Just what this country needs, more liquidator specialists.

I’d settle for a lot fewer economists.

Indeed.

Replace the majority of them with Astrologists for better results. 😉

The storm clouds are building, no doubt, and the reckoning is yet to come, and whether we lock down or not will make no difference to the economics.

It’s a shake out, and the economy that emerges is likely going to be very different. There’s no escaping it, but we could be like the Stockmarket and pretend it isn’t happening.