Big news in NSW where the Berejiklian government is axing stamp duty. Sort of, partly. And after a consultation period.

The government is taking a huge political risk, sneaking in an actually excellent economic reform under the cover of the upheaval caused by the coronavirus.

It could still be the end of the government, as the opportunity to accuse it of “land tax by stealth” is almost certainly too tempting for the state opposition to pass up.

A big opportunity arises here for people who care about policy more than politics: the opportunity for beneficial reform — a better, more efficient tax — rubs up against popular instincts. Siding with good policy is vital.

What does it mean for a tax to be economically efficient? Most laypeople know a lot about economics these days. The intricacies of supply and demand and competition are well known. Aussies are au fait with monetary policy. But the concept of economically efficient taxes is not as widely understood.

The best way to communicate it to people is like this: economy is like an engine. It can run smoothly or experience friction. Taxes are a cause of friction. Efficient taxes suck money out of the economy while creating as little friction as possible. If our taxes are efficient it allows our economy to run smoothly, and grow as big as can be for a given level of population, capital, education, etc.

If we move to a more efficient tax, there is a period where our economy grows faster without having to increase population or build more roads, etc. More jobs are created, wages rise, unemployment falls, etc. So far so good. What’s the issue?

Tax is the price we pay for civilisation (but we’d like someone else to pay it)

Efficient taxes hit stable sources of demand — things where demand won’t change much when the tax comes in.

Here’s the rub: people generally like taxes they can avoid. Taxes on narrow things. A tax on beurre bosc pears would meet little opposition, for example. (beurre bosc pears are those brown ones with papery skin). But such a tax would distort the economy. First consumers would shift to apples and bartlett pears, then orchard owners would chop down their beurre bosc pear trees and replant something else.

By creating an avoidable tax, in the end we collect less revenue than expected and force the economy to contort itself. It shrinks the maximum possible size of the economy. (In our example, trees had to be cut down, farmers whose land is best suited to beurre bosc pears had to pivot, and some people who prefer beurre bosc pears now glumly buy the other kind.)

Stamp duty is like a tax on beurre bosc pears: you can avoid it. You can do so by not selling your house. People renovate the small house they bought at age 28 instead of moving to a bigger one, for example. Australia is obsessed with renovations, even though they are expensive compared to a new build. Part of the reason we absorb that expense is moving house is expensive, because of the tax.

Stamp duty might even cause traffic. We are willing to commute long distances in part because selling up and moving to a better-located house is heavily taxed.

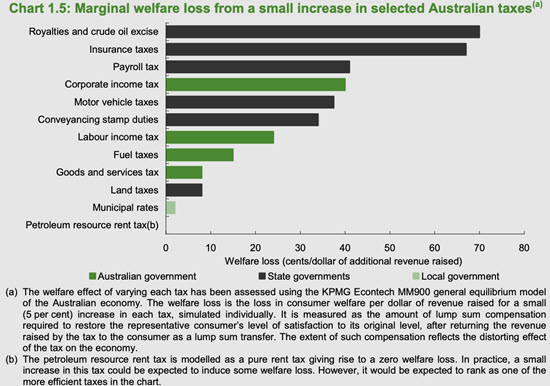

The Henry Review included a chart showing how much of a hit to the economy there was from various taxes. As you will see, several of the worst ones are narrow taxes:

(Incidentally, sin taxes — e.g. taxes on cigarettes and carbon emissions — perhaps explain why people don’t grasp economically efficient taxes instinctively. Sin taxes are the exact opposite. They aim to introduce distortion by shrinking defined parts of the economy.)

A broad-based GST is more efficient than a selective GST for these reasons. Obviously though, taxing narrow categories of things bought by “other people” is politically easy, while taxing big categories of things bought by everyone is politically hard.

Stamp duty is inefficient. Australia’s economy would ultimately be bigger and we’d be better off if we could move house without being taxed for doing so.

If stamp duty’s so bad, why haven’t we already got rid of it?

It says something about how entrenched stamp duty is that it is being grandfathered out in the gentlest, kindliest way possible. The new rules only apply to new buyers. Old buyers won’t be slugged with the new fee. But that’s not all. It is also optional. If you would rather pay stamp duty upfront and avoid the annual fee, you can.

An annual fee for home owners is basically an opt-in land tax. Land tax has two features:

- It is very economically efficient

- It provides an incredible opportunity for a scare campaign: Nanna being taxed just for living in a house!! A tax on the great Australian dream! The state government trying to bleed the average Aussie family dry for having the temerity to simply own a home! An attack on everyday people under the guise of tax reform! Nefarious motives!

State Labor strategists are looking at an open goal. They just need to kick the ball through. The state government is obviously aware of this and rightly terrified. It has declared there will be a consultation period before it acts — which gives it the chance to back down if opposition gets too intense.

The job for people who care about good policy is try to make sure opposition to this plan is not the only voice that gets heard during that consultation period.

A rare occurrence from an LNP Government! It’s good policy, and Labor should just say so and back off! Learn MMT

A land tax is not only efficient, it is equitable in that, unlike almost all other taxes, it taxes wealth, not income or expenditure. As Piketty so compellingly points out, if growing social and wealth inequity is to be reversed (it is at crisis levels in the USA and the UK) then the focus of tax needs to shift from income and expenditure to wealth.

“Taxes are a cause of friction.”

Yeah, I know that economists think that, but is there evidence or proof of it? Taxes in one form or another have been around forever, literally. Do they really cause friction? I think this stands as one of those economic commandments that needs to be re-thought in the same way that Tversky and Kahnemann completely demolished the ‘rational economic man’ myth.

The greatest friction in the economy is not the paying of tax, it’s in knowing you have to pay tax that other people can squirm out of by paying big 4 accounting firms and squirrelling their wealth away in trusts and Cayman Island bank accounts, or that small businesses manage to write off expenses that the PAYE mug pays out of after tax dollars.

And you’ve conflated a few ideas here Jason. Stamp duty is considered an inefficient tax because it distorts the buying and selling of homes, and people would theoretically move more if it wasn’t around. (Another theory that has no evidence, just an assumption based on rational economic man ideas)

But if taxes are friction, you’d just abolish stamp duty and land tax because – less friction! The second idea is that land tax should be enacted because it is an ‘efficient’ tax, and in this sense just means that it’s easy to collect and hard to avoid, not that it’s actually efficient. It doesn’t confer any efficiency at all, except in the collecting. Likely it will have as many distortions and unintended consequences as every other tax.

I like the idea of taxing the wealthy and land tax is as good as any, but beware the economist bearing theories.

I support the Land Tax. We should have had that instituted in all states and territories already… and certain other unfair/inefficient/regressive taxes removed. It would help to reduce the unequal disposition of the ‘economic rent’. Unfortunately, it’ll no doubt receive a similar response to another, sensible piece of policy-change that was proposed before the last federal election.

On first sight a good article Jason, till you describe a broader based GST as a good tax, any GST is a regressive tax not a progressive tax because it impacts harder on lower income groups and takes away from their disposable income and cuts discretionary spending which is the backbone of small business, this is why Scomo`s cuts to jobseeker and jobkeeper will drive Australia into deep recession early in 2021 and for years to come, but that is by design not mistake, its their U.S style economic plan.

It is not the role of taxes to address wealth inequality, this is most efficiently achieved through transfer payments, ie, welfare. That is if conservative governments can resisit using welfare as ideological warfare. The one issue with land tax is that governmemts can’t resist raising them. The opt-in aspect of the NSW plan appears to address this. See IPART NSW’s recent and 15 year old reports on this issue. They were onto land taxes before Henry as it happens.