The great critic Kenneth Tynan once wrote a review of Samuel Beckett in the form of a Beckett play parody. On a stage a critic strides back and forth between two wastepaper baskets, pulling out failed and crumpled drafts of a review from each and reading them. Each time, he cackles.

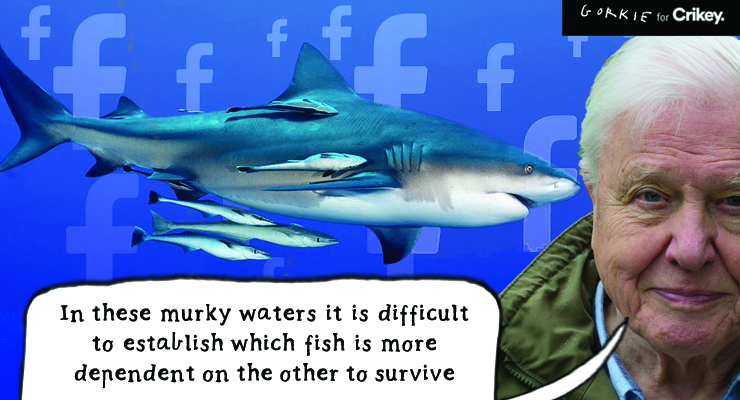

There can be no other reaction from the left to the Facebook-Australian government-News Corp stoush.

At last, a global behemoth wielding monopoly power has been brought to heel! Ah ha ha ha! Crumple, pace pace pace. The pathetic Morrison government protecting media monopoly against free circulation! Ah ha ha! Crumple. Back and forth, unable to know who to hate more.

The government’s News Corp tax has turned a rich tangle of contradictions into a political event. The pleasure of watching the Morrison government’s face change as it slowly realises it might have bitten off more than it can chew is only mitigated by the haunting feeling that we will all lose whatever happens.

At the topmost level is the most obvious political political advantaging of News Corp, by the government, requested or otherwise.

News Corp may have said nothing explicit to Scott Morrison’s government but it didn’t need to; it’s been campaigning against tech/social media on its front pages for years. This global historical moment in tech v old media — the producers of Succession must be furiously rewriting episode nine of the coming season as we speak — has come about in Australia because we’re the “weak link” in the sham idea of a free press and democracy. We’re a Murdochracy, bought and sold, especially, but not only, when the Coalition is in power.

The second level of contradiction is that of capitalism itself. Though it be a grim monopoly at the moment, the tech/media sphere points in the direction of post-capitalism, and the undermining of the legal fiction of intellectual property. Forget the branded nature of “Facebook”. Facebook is simply the corporate form of a capacity of the internet — real time massive peer-to-peer sharing — that became possible at a certain stage of its development.

Had Tim Berners-Lee, rather than Mark Zuckerburg, developed its most efficient version, it would be a free good, non-branded, non-bounded, simply a feature of the internet, linking millions of heterogeneous websites with a set of tools you could opt in or out of. (If Zuckerburg rather than Berners-Lee had invented the web, the whole internet would look like Facebook.)

Though much of it is sequestered in branded forms, the internet is a form that reduces the commodity value of text and image towards zero while offering a faster, more efficient version of knowledge communication than a market based on the exchange of fixed objects (newspapers, in this instance).

The Morrison government stepping in to back up Murdoch — beyond the politics of it — is the state stepping in to guarantee returns for old monopolies that can no longer enforce the exclusivity of their product.

It’s similar in form to the explicit shoring up of brown energy as the entire asset class plummets towards zero, against the ever-greater efficiency and ever-lower costs of renewables. Ironically, Murdoch helped that along when News Corp closed down more than 100 community and regional newspapers in May last year.

People in local communities have been stepping up ever since, using Facebook to create free local news networks — many of which Facebook has now shut down.

Murdoch once argued in an Edinburgh Festival lecture that the rise of the internet meant that there was no need to regulate legacy media ownership. News Corp has been shocked to discover that piece of spin is coming true.

The News Corp war on public broadcasting and social media then began — as it looked to the state to guarantee its capital value — by limiting innovation. This is increasingly the state’s role in a declining capitalism, where money is made from the rents on exclusive rights. Ah ha ha ha. Uncrumple, uncrumple.

The third contradiction is that while digital tech points towards post-capitalism, it does so from within capitalism proper, and the government’s news tax is a bizarre reaching in to private companies to give certain raw materials specific value, essentially doing those suppliers’ bargaining for them.

There is already a law to guarantee the property rights of news suppliers: copyright and fair use. The Morrison government’s law, as m’colleague Keane noted yesterday, imposes an extra cost on the platforms when certain organisations take up the free service-listing or page running that they offer.

It’s as if the old free-listing telephone White Pages was charged a fee every time a cheese manufacturing company was listed because of influence over government of Big Cheese — and the fees gained then went back to the cheese manufacturers.

The incentive would be to start 50 dummy cheese companies and list them all. The incentive for major news corps is surely to pump news through these sites at a huge rate and leverage higher payments.

For the platforms, turning off news then becomes not merely a business decision but possibly a matter of due diligence if the costs can be shown to outweigh the benefits.

As with much state-facilitated corporate capitalism, there is a protection racket at the bottom of it: “Take our product … or else.” Crumple crumple ah ha ha ha.

But that simply indicates the radically asymmetrical character of the two monopoly types under consideration. Murdoch’s monopoly has been achieved by steady consolidation permitted by supine governments, but people do actually have to buy the newspapers.

Facebook, Google and other tech monopolies have become such because of the inherent and massive bias towards any network that establishes early numerical supremacy based on the most infinitely “iterable” internal processes. The Google algorithms are simply “search” got right. Facebook is simply “connection” got right.

They are produced within capitalism as a luxury or pleasure and, like train tracks or electricity, rapidly become an underpinning necessity of the new world they bring into being.

The contradictory nature of the News Corp tech battle is because tech’s radical reach makes its putting into social ownership an urgent and obvious demand. Socialisation either partial — merely through much greater regulation and higher taxation — or wholly, through their taking into part-public ownership, to be supervised by citizens’ and users’ boards, and with a general dividend flowing from their profits to the population.

That is a while away, but it will have to happen eventually, in some global or local form. Its guidance to proximate action is that big tech brings new forms of human connection and communication that — however buried beneath layers of capital, control and surveillance — represent the possibility of organisation other than through the market.

Their capacities, in the hands of capital, may be truly dystopian, but the answer to that can’t be to side with a state that now sees itself as a mere client of old capital — from brown coal to yellow press. The ridiculous spectacle of Murdoch clients across the world wrapping on bandannas to cry freedom should be enough to raise suspicions.

If that doesn’t do it, the prospect of News Corp dictating policy in Australia into a whole new era of communications should. Always bearing in mind that what comes next is possibly worse. Fail more fail better.

Crumple crumple, ah ha ha ha.

Bringing up railways is a good and interesting angle: there are natural monopolies that were (at least for freight) constructed through private investment. The legislative response to these sorts of things is resource access regulations. Anyone can request access to one of these monopolistic resources, and the legislation requires a negotiation. Often these negotiations don’t pan out, because the monopolist may actually have sunk an phenomenal investment into building the resource, and none of the comers can afford the rates. But other times deals are struck.

Much of the discussion of rights of access to the modern “monopolist infrastructure”, or the inevitable socialization thereof doesn’t take into account the phenomenal investments that have been made to make it work. It isn’t only network effects: the product has to be good at what it does. Remember MySpace (as I’m sure many now are…)

Why shouldn’t News or Nine have to pay for access to the new mediums, rather than vice-versa? They paid for paper, ink, delivery trucks and newsagent shelf-space back when those were things.

The point about the history of phenomenal investments is true – rail and tram networks were built at great cost and then the private owners often went broke. The assetts end up being run either by other companies or governments.

For a more contemporary example, look at Iridium – a private consortium put 60 odd LEO communications satellites up for global satellite phone cover in the 90s and then went broke because subsciptions were inadequate to sustain the business at the rates they were charging. The US govt bought them out at a firesale price and the network remains working and charges subscribers what the market will actually bear.

In all the examples, capital took a risk and it didn’t always pay off directly but the network created has often been beneficial in the longer term to all including the investors. Eg, banks might lose on the loans but gain long term from the economic expansion facilitated by the network they financed.

The converse of what you describe had been the utter failure of one of MrsT’s last mad ideas, privatisation of BR.

Several of the carpet baggers who leapt in, including Virgi & Stagecoach, went belly up and had to be rescued … by the taxpayer.

Privatisation of publicly owned natural monopolies is crazy. While spruiked in terms of the supposed benefits to consumers it has invariably benefited the recipients of this govt largesse at the expense of the previous owners.

Thoughtful and insightful as usual. There is a theory in political science that all states begin life as organised protection rackets. Some never get far from them. Modern democracies usually have more factors driving them and more sophistication in decision making. But at bottom they also remained committed to protecting a range of ranked stakeholders with business always in the front. In the crude stupidity playing out now we see the Capo clearly politically intervening to protect his clients/supporters. No national or state interest or benefit in sight. Shows how devolved the current bozos are.

That a large number of Australian citizens, who won’t be winners either way, are jumping about in patriotic fervour just demonstrates why Trump did so well and all those enlistments in World War One,

Re your first sentence, that is the view of James C Scott in his “Against the Grain” and the earlier “Seeing the State“.

..oops, your 2nd.

Thanks for those refs. Will have a look. I think I first came across it in Vadim Volkov’s Violent Entrepreneurs, where he was exploring the dynamics of post-communist Russia. There is lots of work done in historical sociology on the rise of modern state that also develops this theme.

Re the Russia thing, a lifetime ago I acquired a private library collected at the start of the 1900s, which necessarily included many of tacts of fact, travellers’ tales and derring-do in the Tzarist Wild East.

The latter were mostly Raj types engaged in the Great Game but quite a few were true adventurers, certifiably crazy in Victorian society, from whom I learned enough not to be surprised by the results of the dismemberment of that mad experiment of a soviet on which the Sun barely ever set.

… also “included many tracts of fact..”

At the heart of Gorbachev’s reform program was the transformation of the Soviet Union to a law based state, ie rule of law. This was antithetical to a system where law was just another political-economic tool. Under Yeltsin the state more or less failed and competing gangs fought over assets and enforced their own laws while bargaining with, using and corrupting the weak state. The native Russian political scientists and journalists referred to them as clans. Putin, along with his clan coming out of the former KGB, subdued them and became the godfather. They still exist but must pay tribute and he arbitrates their disputes. Australia is not Russia but you can see echoes in this media scheme and other protections offered to our oligarchs. Scotty from marketing is no godfather though, he is way too much of a supplicant.

On pre communist Russia the Marquis de Custine’s works have a de Tocqueville quality and I highly recommend them. Interested in titles of the other refs you mention.

Alas, currently those tomes are half a world away from this lamenting Exile.

I’d recommend Peter Fleming (Ian’s older, much resented, brother – far better read and a superior writer) who traversed the Far East post WWI, from Vladivostok via Harbin, as an emissary to the White Army. He chose not to share their fate and made it to Tibet on foot to reach the Raj via what is now the China-Karakoram highway.

erratum – Scott’s earlier work was “Seeing Like a State“

Who to hate more?

That’s a no-brainer.

Despite that fact that I find Facebook utterly insipid I’ll take the Zook ahead of the Rupe any day of the week.

Murdoch gave us Trump FFS.

In any case when the government threw their spineless lot in with News Corp (et al) the choice was set in stone.

“Zook Vs Rupert the Sook”?

Our media (and part of society with it) like an addict having to go cold turkey – when the tabloid msm is a user/dealer/pusher.

Facebook (like a wall of telephone box “advertising”) was generating publicity and referrals to those media houses of ill-repute for free – now that fading, wrinkled, increasingly fetishist, tabloid press wants to charge those post-it pimps for the service they were providing for free, because the msm business model is haemorrhaging john interest.

“The Morrison government stepping in to back up Murdoch — beyond the politics of it — is the state stepping in to guarantee returns for old monopolies that can no longer enforce the exclusivity of their product.”

Except the media competes in two markets: the market for viewers and the market for advertisers. It sold is viewers/readers to advertisers. But then along comes big tech that’s more efficient at delivering consumers to advertisers, hence the problems for traditional media. If there was any “exclusivity of their product”, it wasn’t content, the product was delivering viewers/readers/consumers to advertisers.

A product that is much better at delivering audiences to advertisers has disrupted old media. That’s capitalism. Old media should have to adapt or wither away. What’s this about uber-capitalist media conglomerates seeking protection from the State (to which they avoid paying any tax).

Why not create a union of Buggy Whip & Candle Stick Makers whilst they are at it?

They pay tribute instead.

And, as for withering away, instead we get “Scotty’s Whacks Worx” – a working museum of past technology, subsidised by the tax-payer – with profits going to Murdoch’s chamber of horrors.

During MrsT’s unlamented reign Moloch was hot to trot with new technology, gutting Fleet St by moving to Wapping & Canary Wharf to be rid of the new for all those clanking ancient printing presses and annoying soft machines invoking ‘traditional Spanish holidays’, copy boys and other unnecessary costs.

By setting up computerised editting & printing in new premises, protected by police and his private security army, licenced by state fiat, he did away with 60% of wage costs.

Funny what happens when so much capital is tied up in a distressed and diminishing assent.

Rentiers of the World Unite, you’ve Nothing to Lose but your Wealth!

It seems to me that Google’s and Facebook’s business models are a bit like free to air TV. Advertisers pay handsomely to get their stuff broadcast. As many ads as possible are embedded (crammed) into streams of stuff that people actually want to watch (content / programs). The TV stations pay for content, content producers don’t pay the TV stations to broadcast it. Some content is produced or curated by the stations themselves but when they do they pay for externally-sourced content, e.g. news services.

Basically, the old media now require that the Government to protect them from “unfair” competition. Maybe the long-forgotten butter-margarine wars of the 1960s would be a parallel. Be that as it may, the Government is happy to oblige because the old media by and large support it, with Newscorp Australia acting as its propaganda unit as required. Never mind free markets, which would require that the old media adapt or go the way of buggy and bullock dray builders.

But then, no one actually believes in free markets, least of all Big Business

Cannot disagree with a word of that, esp. the sign off.