Given that David Walsh, founder of MONA and Dark Mofo, made his fortune off gambling, it might have been worth taking a bet on when his festival of transgression would eventually really land itself in it. The “we want your blood” controversy currently engulfing Dark Mofo would appear to be it.

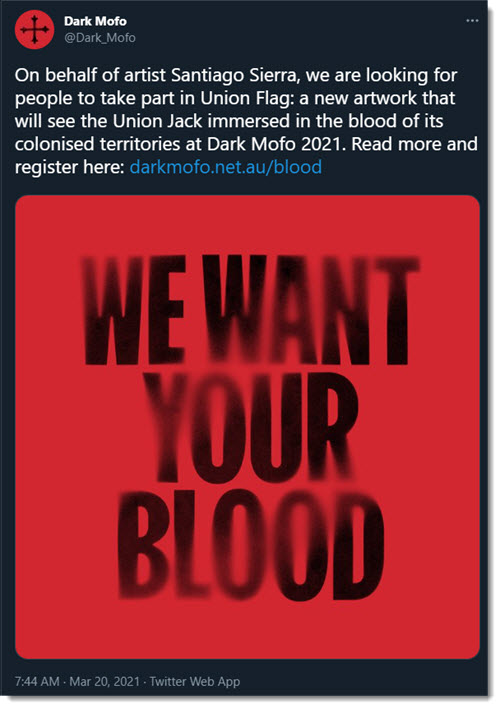

The festival — which takes over Hobart for a couple of weeks, usually in the winter — advertised with a raw red poster and alert for Indigenous people to donate their blood so that it could be soaked into a Union Jack.

Artist Santiago Sierra described it as a comment on colonialism, presumably the horrors thereof. Indigenous and other artists disagreed, to put it mildly, and more than a hundred participants signed a petition demanding not only the artwork’s cancellation, but that Walsh’s MONA complex thoroughly reform its curatorial practices, have all staff and management undergo cultural awareness training, and various other reparations.

Dark Mofo director Leigh Carmichael looked like he might tough it out for a while before he caved, as did Walsh, cancelling the work and adopting the language of anti-colonialism and trauma deployed by the protestors who had demanded that Dark Mofo be a “safe” space for artists.

And, well, that’s pretty much the end of Dark Mofo ain’t it? I mean, as a festival of transgression and edge. Perhaps that was only a matter of time.

There was always something bizarre about the festival’s wild success in the Apple Isle, whose public morality is split between Christianity and green-secularism.

As representatives of both clenched their teeth, Dark Mofo and MONA became major tourist drawcards and part of Tasmania’s global branding. Yet that drew the festival into a paradox.

Its identity and energy were drawn from a European avant-garde tradition of transgressing morality, at the same time as the progressive class and the cultural-producer elites have built new collective identities around the enforcement of ever more specific moral rules.

The confrontation was never going to come around Dark Mofo’s usually jejune attacks on western religion. Now they went and did something a little more interesting and it has all come apart.

You can see the point being made by the protestors about the in-your-faceness of Sierra’s work. It’s not a single event in a gallery you choose to go to, but widely disseminated by a festival; sort of Satan’s Moomba, now an arm of the state. It’s by a non-Indigenous artist, it’s kinda tiresome in its staginess, etc. But on the other hand, protesting artists — I mean, it’s all a little grimly funny. What is it that first alerted you to the “unsafe” qualities of a festival called “Dark Motherfucker”?

Was it the neon Satanic inverted crucifixes around town? The guy using the fresh remains of a slaughtered bull? Heh… The protest over “We want your blood” shows that the transgression of events like Dark Mofo has always been a packaged one, held within limits, which conformed to the secular-humanist values of the knowledge class.

Since these are now the dominant values of society — it’s been decades since they defeated a remnant religious-cultural order, what progressive value or statement could possibly be challenging or transgressive now? — Dark Mofo has had the challenge of declining energy for some time.

Recently, it added a “dangerous thought” mini festival. But since the dangerous thoughts of our time are all those adopted by the alt-right now (what if monocultures are better than multicultures? What if the triumph of gender over sex is a cultural disaster? What if war is necessary to the health of a society? What if global colonialism was a necessary precursor to full human liberation?) the progressive avant-garde’s claim to edge is permanently stymied.

“We want your blood” did have a bit of sizzle about it — whatever the artist tried to fix as the work’s meaning it had other, darker ones — but that’s not what Dark Mofo’s for. It’s for having a black vanilla ice cream, seeing a three-hour movie about sodomy and then going on a ferry ride. Kids get in free. It’s a theme park of a concluded artistic modernity.

Trouble is, so is the attitude deployed by the artists protesting the event. What the hell concern do artists have with MONA and Dark Mofo being “safe” — meaning not that loose scaffolding is secured but that nothing “traumatic” will be seen or heard? How can art even begin to work on this principle?

Both Walsh and Carmichael should have pushed back much harder against the implicit notion that there’s some sort of right to not encounter anything disturbing or upsetting. Art has to have a certain autonomy of creation and a right to come into being, as it were, as a necessary part of a wider right to free expression. How is it possible to defend someone’s right to call for Australia to “burn to the ground” at a rally and then apply collective censorship, on psychological “safety” grounds, to a piece of art?

The inevitable result will be that the “safety” motif is rolled over into political discourse to shut down protest. Such acts are the expression of grant-fed artistic networks which have become arms of the state, to produce a safe, authorised art of pseudo-dissent.

The eventual result is that artistic mediocrity, the production of a sameish avant-garde kitsch and disengagement as the pursuit of safety, and the avoidance of trauma become an ever-tightening circle. Such wars to shut down expression are acting as a substitute for real politics in any case.

Tasmania, after all, is the place where activist Michael Mansell started a sovereignty push with money part-provided by Colonel Gaddafi. How unsafe was that? The search for “safety” is nothing other than the consolidation of an elite order, to which a section of artistic elites have been admitted.

Those who want real change should have nothing to do with it. Art and politics and life are meant to have a bit of fate and chance about them.

As I understood it, the objection is not that people won’t “feel safe”, but that indigenous people were asked to contribute for nothing to someone else’s artistic expression.

And the someone else happens to be a national of one of the few countries with a worse background of indigenous massacre than Australia.

There’s a difference between being offensive and being transgressive. The transgressions should punch up and make those with institutionalised power feel uncomfortable, not punch down at minorities.

If the bloodsoaked flag installation had been conceived and executed by a local Indigenous artist rather than a foreign European one, it may well have been welcomed and celebrated. But Dark Mofo made the right call to cancel it in this form.

I don’t think they’re at risk of selling out or losing their edge.

“There’s a difference between being offensive and being transgressive.” Is there? If an artist transgresses norms, s/he is going to offend the people to whom those norms are important, regardless of whether they’re “punching” up or down. Your identification of transgression with punching up is merely a way of deciding the question in advance, in a way that supports your own worldview. There have been plenty of rightwing artists, from Goya to Dali to Cocteau, who were both transgressive and offensive and so wouldn’t meet yr criterion. I wouldn’t have shared their political views, but I can recognise their art as great.

As for your suggestion that the artwork wouldn’t have been offensive if it had been conceived and executed by an Indigenous artist – the logical endpoint of that view is that an artist can’t represent what s/he takes to be a great historical injustice to a community unless s/he comes from that community, which goes against any notion of art as involving representation/imagination/empathy. That’s an anti-aesthetic, dressed up as aesthetics.

The work wasn’t cancelled for aesthetic reasons, but for social and political ones, involving power of different kinds, from people who have very little of it, and people who have a bit more of it and try to speak on their behalf. The article was an honest attempt to anatomise that struggle, and the contradictions that emerge from it. The reaction against it is a moral one, no different in kind from a born-again Christian demanding the removal of Piss Christ.

I pissed myself when I heard that a Spaniard was the edgy provocateur behind the donor drive.

That’s probably because I missed his apologia colonia in Mexico, Peru, The Phillipines etc.

Vintage Rundle. Only truly dangerous writer in town. Bravs.

An ersatz Thompson, to challenge the ersatz mofo.

Worth noting that in the Mercury today Michael Mansell urges reinstatement of the work and says “the real losers of the cancelled exhibition are Aboriginal people. The decision to remove the exhibition means there will not be any public debate about the topic the artwork raised…Silence about the past means leaving things in the past.”

Thanks Citizen. I was always wary of Mansell, not sure if he was representing himself or his people, but time seems to be pointing towards him showing the path. My only concern about this was whether it was an indigenous ‘voice’ that was against the project, or just a few with a megaphone. I’ll assume the jury out, for me, and let them decide.

I suspect that many of the left (whatever that means) have long been looking for an excuse to deal Mona a blow because DW made his money from gambling.

Mona is getting progressively quieter as it gets older, that appears to be the nature of most living things. It may be the way but it sad non the less. This would not be an issue in Europe or the USA and the outrage about the bull was weird, that stuff was happening in Europe 50 years ago.

When Mona started it was playful and challenging (the quad bike races, the goldfish and shadow installation, Art Gonzo), much wasn’t, in my eyes, ART, but it stirred the art world internationally, so much so that Museum newsletters were really excited. Not, I think, so much anymore.

I love Mona and I don’t mind it getting old, so I’m Ok either way, but Art must stimulate, it doesn’t have to challenge but must stimulate, so perhaps if the blood donations had been from the descendants of the invaders it would have been more acceptable.

I find the “strike” by the artists really depressing, there is so much more to praise about Mona and so many other things to condemn outside of Mona.

They clearly stuffed up in the eyes of many, but they apologized immediately and acted straight away. More than can be said about our politicians and religious and business “leaders”.

I like the line that art has to stimulate, not necessarily challenge. I’ve too often found that some ‘outrage art’ has been produced only for its challenging, without really stimulating anything. A few pieces come to mind, I thought it was akin to shooting fish in a barrel. I’m ambivalent about this case, but if the indigenous people are against it, I’m always going to side with them.