While Australia managed one of the most impressive economic performances in the world in 2020 — not much of a boast, true, but significant nonetheless — it seems the government’s twin crackdowns on spending and wages are going to pull us back to the economic pack this year. At least according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook out this week showed Australia outperforming most developed economies in 2020 with growth of -2.4%, compared to less than -5% in Europe and -4% in the US. Most of that is down to Australia being isolated, the states’ mostly effective lockdowns and contact tracing, and the Morrison government’s highly effective fiscal support via JobKeeper, JobSeeker and the HomeBuilder program, as well as the aggressive loosening of monetary policy by the Reserve Bank.

But this year and next are shaping up as less than stellar: the IMF sees us growing 4.5% this year and 2.8% in 2022. That compares to global growth of 6% this year, 4.5% and 4% for Western Europe, 6.4% and 3.5% for the US and more than 5% both years in the beleaguered UK. Most of these forecasts have been upgraded — the US forecast was raised by 1.3 percentage points from the IMF’s 5.1% 2021 projection in late January and is now nearly double the rate estimated last October, when the Trump administration was destroying the United States every way it could.

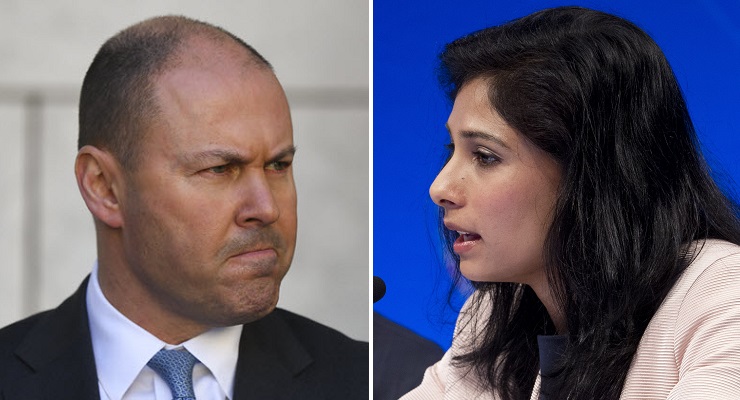

Why are we going to go from champs to chumps in economic growth this year after our success so far? The IMF’s chief economist Gita Gopinath said the global improvement recorded in the latest forecasts was largely due to increased fiscal support, and particularly the new US$1.9 trillion spending package from the Biden administration, accelerated vaccinations and continued adaptation of economic activity to overcome pandemic restrictions.

In contrast, here in Australia fiscal stimulus is now being rapidly withdrawn and the government has so badly botched the vaccination rollout it’s unlikely it will be completed this year, condemning Australia to remain walled off from most of the world until 2022.

Couple that with the Coalition’s war on wages, the latest front of which is the government’s opposition to a pay rise for low-income earners via the Fair Work Commission annual wage review (and remember the FWC is increasingly stacked with right-wing ideologues and partisan hacks such as Sophie Mirabella). Add in its active suppression of public service salaries, an industrial relations bill that made work more precarious and wages and conditions easier to cut, and you can understand why the Reserve Bank doesn’t think there’ll be decent wages growth until 2024, despite bond market screen jockeys and neoliberal commentators frothing at the mouth about inflation.

For the umpteenth time governor Philip Lowe repeated the mantra on Tuesday, even if Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg aren’t listening.

… Wage and price pressures are subdued and are expected to remain so for some years. The economy is operating with considerable spare capacity and unemployment is still too high. It will take some time to reduce this spare capacity and for the labour market to be tight enough to generate wage increases that are consistent with achieving the inflation target.

It really does say a lot about both the influence of the Liberal Party’s big-business donors and the rabid zealotry of both ministers and backbenchers that the government’s response to this plea from the Reserve Bank is to try to reduce wages growth further.

And despite the constant and growing animosity between Australia and China, we still remain heavily dependent on the Chinese economy and it remains heavily dependent on our iron ore. And that’s good news for our growth: the IMF sees further improvement in China. It recaptured all of its lost GDP growth by the end of 2020 and its growth forecast for 2021 was raised by the IMF by 0.3 percentage points to 8.4%. That’s mostly due to strong demand for Chinese exports, not strong domestic demand.

The Chinese economy has been and will continue to be supported in part by the US stimulus spending, which is lifting demand for Chinese exports. Imports remain weak and increased public spending is helping drive the commodity price surge in products such as iron ore, LNG, copper, grains and a rebound in coal.

Not merely is that US stimulus spending helping other economies, it also meant the rate of expansion in the US manufacturing and service sectors in March exceeded that of their Chinese equivalents.

After four years of disarray, death and disaster under Trump, once again the US is the engine of global growth, with expansive fiscal policies and a commitment to wages growth. Australia risks getting left behind with fiscal austerity and a war on wages.

“the Morrison government’s highly effective fiscal support via JobKeeper, JobSeeker and the HomeBuilder program”

Highly effective in delivering bonuses and dividends to those who don’t need them?

Homebuilder? Was that actually effective? Were there more than a handful of people who used that?

I live in a town of 30000 and there are houses going up all over like mushrooms. You can’t get a tradie for love nor money, and the price of bricks has more than doubled. So, yes, Homebuilder seems to be effective.

Homebuilder has actually stimulated the housing boom – making it harder for the young to buy their own homes

Exactly ! They had to make up for the 200,000 new bodies they were importing each year – – Just to stimulate the Housing.

Obviously no need to follow the recommendations of the Banking enquiry.

Effective in driving up rents, particularly for the financially marginalised. Talk about having your cake and eating it too. Renovate the investment property for free thereby increasing its value, pay considerably less interest thanks to the current low rate then revalue the property upwards for rental purposes. Nice gig if you can get it.

Some builders are ‘booked out’ for up to 2 years especially for ‘new builds’. The flow on effect is a steep rise in the price of established homes. No real space for young Aussies who are not hooked up to the Bank of Mum and Dad to have a real opportunity to buy. Job insecurity is not helping either.

Further proof, were it required, that economists exist only to make astrologers seem rational & fact based.

“After four years of disarray, death and disaster under Trump, once again the US is the engine of global growth, with expansive fiscal policies and a commitment to wages growth. Australia risks getting left behind with fiscal austerity and a war on wages.”

What a joke ! The USA is falling apart & is NOT the engine of Global growth. I’m no Trump fan but Biden is only just semi concious & a War monger. Just as he was when VP to that other War Monger Barrack Obummer.Trump didn’t start any New wars but Biden has already made the noises to start a War with Russia for starters — and China with sending Battle Fleets through the Taiwan straights.

Oh -and the Chinese won’t be dependent on our Iron Ore for too much longer. This whole article could have been written by any 5 Eyes MSM – expected something different & more accurate from Crikey.