Somewhere amid the Big Macs and hot apple pies an extraordinary scene played out in a suburban McDonald’s which, 20 years on, still has ramifications for the men involved — and the ever-expanding Hillsong Church.

It was here in the fast food fantasia of McDonald’s Thornleigh in Sydney’s north that two of the biggest names in the Australian Pentecostal movement met to dispense quick justice to a man who had been sexually abused as a child.

The deal was done with the promise of $10,000. In exchange, the then-38-year-old victim Brett Sengstock signed a soiled McDonald’s napkin.

It meant Sengstock had come face to face with Frank Houston, the man who had abused him as an Assemblies of God (AOG) pastor decades before.

Fronting the commission

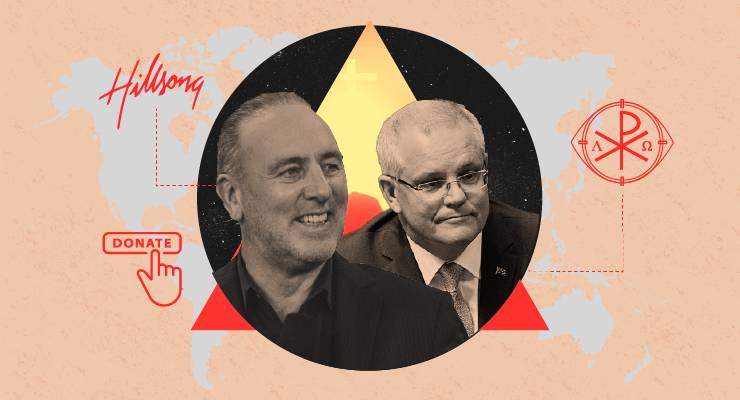

Just how tawdry the whole episode was became apparent at royal commission hearings 15 years later. Frank Houston’s son Brian — by now the head of the sprawling, glitzy Hillsong phenomenon — agreed that his father promised the money in an attempt for forgiveness “and going to God with his heart right”.

He also agreed that the traumatised Sengstock had been forced to chase up the $10,000 promised at Maccas — two months later, according to Sengstock — because Frank Houston hadn’t organised it. It took a further month for the cheque to arrive and when it did there was no correspondence attached.

And who was the third man in the trio? Houston explained that was Nabi Saleh, an old friend of the Houstons. “He loved my dad and I think he just — all he was concerned about was looking after my father in terms of driving him there and being there to comfort him,” Houston told the commission.

But there was and is more to the Nabi Saleh story. Saleh is a man of many hats. He was the multimillionaire owner of the Gloria Jean’s coffee franchise and a Hillsong Church elder when the Sengstock deal was done. According to Brian Houston, Saleh had also come with him — “as a family friend” — when Brian met lawyers prior to the McDonald’s meeting.

Saleh was aware of Frank Houston’s crimes and was party to a dirty deal, done dirt cheap. How deeply involved, the royal commission doesn’t say. Ultimately it made no conclusion on Saleh’s conduct. Saleh has not responded to questions Inq put through Hillsong.

Saleh sits at the apex of Pentecostalism in Australia today. He is on the board of close to 20 Hillsong entities registered with the Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission (ACNC). He is also a director of the Kenneth Copeland Ministries Eagle Mountain International Church Ltd, the Queensland-based affiliate of the massively influential and hugely wealthy US preacher, Kenneth Copeland.

Brian Houston was ultimately censured by the royal commission for the way he dealt with the Sengstock case when he was the head of AOG in Australia. Houston, the commission concluded, had a conflict of interest which the AOG’s national committee failed to recognise. The AOG’s national executive, of which Houston was president, had failed to report the allegations to police, despite being required to by legislation.

(That committee included Pastor Wayne Alcorn, the current head of the AOG’s successor organisation, Australian Christian Churches. Alcorn shared the stage with Scott Morrison at the PM’s recent Gold Coast conference appearance.)

Despite his attempts, Sengstock received no further compensation before or after the royal commission hearings. Frank Houston died in 2004. Sengstock’s case foundered on the grounds that AOG Australia was not legally responsible for Houston. Sengstock is now ill with stage-four cancer and did not answer Inq’s request for a comment.

None of this, though, has stopped the ever-onward march of Hillsong.

Public trust

Houston and Saleh are directors of Hillsong-related entities which receive millions of dollars in government support via tax exemptions. The Hillsong entities in Australia collectively received more than $70 million in donations, most of that in tithes, according to Hillsong’s 2019 annual report. All of it is tax free to Hillsong.

All of this is perfectly above board. The charities law has carved out a special place for a class of religious charities. The ACNC does not have the power to remove a member of a charity’s governing body. A so-called basic religious charity generally does not need to submit financial reports. Nor does it need to comply with the ACNC’s governance standards which apply to secular charities and are designed to “help maintain public trust in charities”.

(Hillsong is registered with ASIC so it must disclose some financial data, unlike the more established denominations that operate in almost full secrecy thanks to acts of Parliament.)

These rules have enabled Hillsong to build a business model made in heaven.

None of the organisation’s entities are required to pay income tax. At the same time, Hillsong has access to vast amounts of unpaid labour. ACNC records show Hillsong Church Australia operates with the help of some 5790 volunteers, covering its various trading arms, which include a restaurant (Bella Burgers), a cafe (Comma Coffee), and two education providers (Amplified Education Academy and Hillsong Night School.)

Its music productions which provide the trademark razzamattaz of a Hillsong gathering are almost entirely run by volunteers, with more than 1800 unpaid workers.

Hillsong is also able to access costly expert advice free from its board of directors, covering real estate, marketing and accounting. One of its directors, Phillip Denton, is a major real estate developer in NSW and Queensland through his company Hillscorp.

According to Alec Spencer, a former executive officer in the AOG movement and now a James Cook University PhD candidate investigating the public funding of religious institutions, there are over a dozen religious-specific tax exemptions, concessions and exceptions, with many of them operating without any overarching public policy agenda regarding the public interest or public benefit.

Born in Australia, made in America

But Hillsong’s masterstroke, Spencer says, has been to internationalise its operations, such that Australia is now only one part of a giant entity largely domiciled in the United States.

“They are now taking their broadcasts into 160 million homes around the world via the Hillsong digital production arm. They have been way ahead of other movements on this,” he said.

“It means that they are able to solicit donations and skirt Australia’s complex, archaic and clumsy fundraising laws, which are incredibly onerous with 76 different regulations at state level.”

It also means that Hillsong has a slice of the estimated US$1.2 trillion religious market in the US.

Tomorrow: Inside the US money machine and the power of donations.

And of course they preach a “prosperity gospel” because that allows them to justify their own greed and excess! How many Jets does Houston own again? Jeez……people are so gullible……..how did humans survive with those genes?

The state needs to step in and create a State Religion, the private sector needs some real competition.I always fancied the old Roman Gods myself.And if it was successful it could then be privatised and sold to the governments mates.

With 7 Pentecostal Ministers, it’s well on it’s way to being the de-facto religion. Nope, no conspiracy to see here???

It’s been done already. See the Universal Roman Church created in the 4th century. Now better known as the (Roman) Catholic Church. The old Roman gods kept bickering with each other and one god is much easier to manage than many.

The vast majority of Americans practice a state sponsored demonic religion loosely based of a few bible stories. Their primary prayer being *Support our Troops* If god exists then god would regard them as the anti-Christ. My favourite Roman god is Sterquilinus.

Sterquilinus – the god of shit. Love it!

Damn moderators! Sterquilinius – the god of ‘merde’. Love it!

Define survive…perhaps add a timeframe…

End the free ride for churches now. Churches have never contributed anything of value to their congregations. Unfortunately they give the status quo a compliant mass to rip off so unethical governments are pretty keen on them. If we ever get a government serious about looking after their constituancy they need to end this rort.

Plus 1,000

While I agree in ending the free ride for churches, it’s a bit of overreach to say they contribute nothing to their congregation.

Churches provide community, an in-group to belong to, a place where the individual is accepted. That’s why they endure, despite largely being a relic of times past.

And a place where male and female children can be deprived of their innocence by perverted pastors, then bought off to protect the even worse managers of the religion.

Easily obtained statistics show a 100x higher rate of paedophile activity in the secular world, most predominantly in the same family or close friends.

The added value is not just necessarily to their congregations, but to the community at large.

Most, but not all of the funds collected are used to support and supply charities and charitable works funding in the community. People receive food, bill relief, housing etc.

All employees pay income taxes on their wages so the tax free status only applies to the church income that is used for community purposes ( ie returned to the community).

“The charities law has carved out a special place for a class of religious charities. … Nor does it need to comply with the ACNC’s governance standards which apply to secular charities”

so, easy fix, make the the god-botherers follow the same rules as the other charities

Aren’t we missing something Roberto? Like a small but growing political coterie already ensconced in Canberra ‘tower of power’?

Or even better, follow the same rules as all other businesses. They are highly profitable businesses, with the primary happy clapper group operating in multiple industries. Let them pay proper taxes and compete on a level playing field.

Just. like Amazon and Apple.!

Simply demonstrates that this pseudo religion, in common with all the others, needs to be taken off the public teat and some of its bosses need to be prosecuted for their complicity in sexual and other crimes.

Here’s $10,000 for being abused as a child.

That’s it?

Really?

Brian Housten seems to be well into psychopathy, to be able to consider that the church he took over doesn’t owe a man who had his life destroyed a decent amount of compensation.

Disgusting, really and truly disgusting.

And this is the man our Prime Minimal describes as a close personal friend.

Oh well , if you fly with the crows and you will get shot down with them too.

Are these people still holding back from the compensation scheme for abused children ? If our prime minister had any guts, he would legislate to compulsorily acquire some of their ill-gotten gains and apply it to the fund.

He’s too involved with Houston to do anything, and now he’s enrolled more and more Libs into the scheme he’s placed the noose around his own neck if he does need to do anything Houston wouldn’t like. “Oh, the webs we do weave when first we consider to deceive.” Morrison will soon be hung by hus own petard.

I’m waiting to hear how many of his cohort, on leaving politics, quietly become pastors of their own” hurches” now they’ve seen just how much money can be raked in, plus you don’t have to pay the workers who do all the heavy lifting that makes you mega rich, because that’s all they want out of life – money and power.

“Morrison will soon be hung by hus own petard.”

I initially glanced at that was “Morrison will soon be hung by hus own leotard” and thought, did Dolly Downer have a xxxxsoul mate?