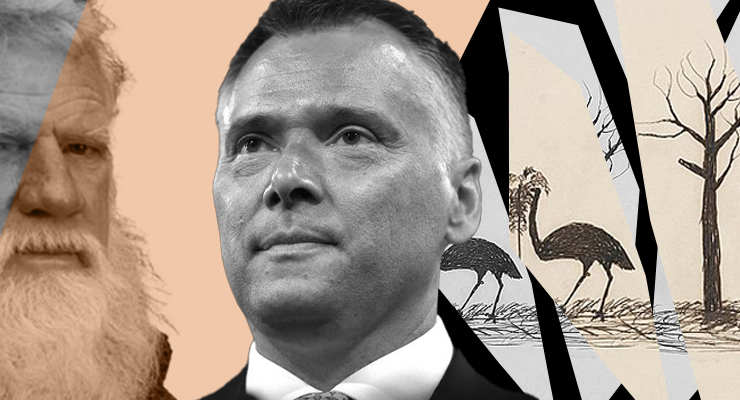

If Dark Emu is as flawed as scholars Professor Peter Sutton and Dr Keryn Walshe suggest in their book Farmers or Hunter-Gatherers? The Dark Emu Debate, where does this leave Australia’s literary and cultural institutions which have embraced Dark Emu and its author, Bruce Pascoe?

Veteran publisher Richard Walsh has several decades at the top of the industry in Australia and says Dark Emu has been a publishing phenomenon because ultimately it represents something Australians want to believe in, though it now “desperately” needs to be revised.

“I don’t believe it is a fatal blow intellectually,” he said. “The core argument is correct but some of the peripheral material needs to be re-evaluated.”

Walsh is a commissioning publisher at Allen & Unwin which in 2011 published The Biggest Estate on Earth by ANU historian Bill Gammage. It covered similar themes to Dark Emu and was a major source for Pascoe.

“But Bruce is different to Gammage,” Walsh said. “A scholar will stick with the facts that one knows and not extrapolate at all. What Bruce has done is put a V8 engine into a VW Beetle.”

Figures from book tracking system BookScan show Gammage’s well-regarded work sold about 50,000 copies. Dark Emu, has already sold about 250,000 copies — a demonstration, Walsh says, of its “enormous appeal to progressive white folk”.

“The world was waiting for Bruce’s book,” he said. “You have to remember that publishing is an act of faith. We have to trust the author to a large extent. And we have a soft spot for people like Bruce.”

The publisher

The fallout is particularly troublesome for Magabala Books, the publisher of Dark Emu, which has profited mightily from its enormous popularity. So far Magabala refuses to acknowledge any problems, instead pointing out Dark Emu‘s success in stimulating “an important discussion and debate in Australia”.

“Bruce Pascoe has presented a strengths-based understanding of the wisdom and complexity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander societies, knowledge and achievements,” Magabala said in a statement to Crikey.

“The book has sparked a greater interest in our shared history among everyday people in a way that few other books have done. Informed and constructive debate is healthy and vital to the development of who we are as a nation. It is also important that this discussion finds its way out of the academy and into mainstream understanding. Magabala Books is proud to have published Dark Emu.”

The documentary

In 2019 Screen Australia threw its support behind a high-end documentary starring Pascoe as narrator of the television version of his book. The project has also drawn support from Screen NSW and Film Victoria. The ABC will screen the two-part documentary and saw it as an opportunity to “correct stereotypes”.

The ABC will not answer questions on the commissioning process. It tells Crikey the documentary would continue but that it was “too early to offer anything of substance as to what impact, if any, the new book will have on the program”.

The awards

In 2018 — four years after the first release of Dark Emu — the Australia Council gave Pascoe its coveted lifetime achievement award in literature.

The most critical award, one which helped propel the spiralling success of Dark Emu, was the 2016 NSW Premier’s Literary Award. The awards were a coup for Pascoe, his book and Magabala Books. Dark Emu won book of the year and with it a $10,000 prize. Pascoe also came in as joint winner of the (inaugural) Indigenous Writers’ Prize, taking a share of the $30,000 prize. The money was secondary — prestige was the real prize.

The ringing endorsement of the NSW judges is now reproduced in Dark Emu. It is a “vital” book, the judges say. It injects a “profound authenticity” into how we understand Australia. Pascoe demonstrates his case with “convincing evidence”. The book “reveals enormous Aboriginal achievement in governance and agriculture, and restores these to their rightful place at the epicentre of Australian history”.

It’s “essential reading for anyone who wants to understand what Australia once was”, and Pascoe, they say, is “a voice at once catalysing and unifying”, without peer in his field.

Is the NSW government intending to revisit the award in light of the damage inflicted by Sutton and Walshe’s book? The award’s administrator, the State Library of NSW, refuses to come to the party with any sort of answer or defence.

“The State Library is aware of public discussion about Dark Emu and the arguments it contains,” it said in an email to Crikey. “Awards are recommended by an independent panel of judges, and the library does not comment on their decisions.”

And that’s it. Case closed, apparently.

The other voices

Crikey has spoken to journalist and author Stan Grant, who was one of the judges of the 2016 Indigenous Writers’ Prize, alongside the much-awarded Aboriginal writer Melissa Lucashenko (winner of the 2019 Miles Franklin award for her book Too Much Lip), and celebrated author Thomas Keneally.

Grant says he was being asked to judge Dark Emu not as non-fiction but in the broader category of Indigenous writing.

“I was looking at Dark Emu as a piece of literature and I actually didn’t rate it as highly as [co-winner] Heat and Light [by Ellen van Neerven], so we voted to make it a shared winner,” he said. “In terms of the facts of Bruce Pascoe’s book, I think academic rigour and evidence matter a great deal. But I think we’re also talking about something different and that is our need for a myth.”

Pascoe, Grant says, is “operating at the level of the storyteller”.

“Australians have bought Dark Emu because they want the myth and in Bruce they see the embodiment of that, the ostensibly white man who reinvents himself as an Aboriginal person,” he said. “Bruce Pascoe has said he is taking Australians to a mythical hitherto unseen and unknown place. That’s what Australians are buying: a myth. And myth is often more potent than fact.

“After all, Australia is built on myths. The great myth of terra nullius — the idea that there was no one here — is the legal foundation of Australia. And do we really have to know the facts of Gallipoli to share in the powerful myth of Anzac.”

Lucashenko was chair of the group that awarded the Indigenous Writers’ Prize and was part of the panel that awarded Dark Emu book of the year. That panel was chaired by filmmaker and producer Ross Grayson Bell.

Lucashenko says she had known Pascoe for 24 years. “Uncle Bruce is respected and loved,” she said. “I think these attacks are coming from people who are jealous of his success. I saw the white-anting start the night he won. No one said much when Bruce was writing mid-level books.”

Walshe, co-author of the critique of Dark Emu ,has been alarmed at some of the “facts” in Pascoe’s book but stops short of calling for the award to be reviewed.

“That could be a treacherous path,” she said. “But there should be much more rigour built into the process of assessing non-fiction works before it gets to the point of being judged. It gets very political and it needs to be assessed in a more neutral environment.”

And on the question of Dark Emu‘s value in promoting a different view? “It’s not about views,” Walshe said. “It’s about the truth.”

2014-2018 – commentariat hyperventilates itself into a belief that Dark Emu has totally remade all previous Australian understanding of our past; 2018-2021 – commentariat whips up a scarifying attack on Pascoe and totally denounces his scholarship and integrity.

Let’s calm down and recognise that all history books are ‘a history’ not ‘the history’. And equally, recognise that some of the critiques have pointed out deficiencies in Pascoe’s scholarship while others are nit-picking or minor re-assessments.

Let’s debate, not lionise or denounce.

Exactly, it is not a contest where one is right and the other wrong. That is how media portrays it, but that is not how scholarship works. It is one viewpoint of many which may all be largely correct and will be adjusted as more knowledge comes to hand. Remember the blind men and the elephant.

‘The ABC will screen the two-part documentary and saw it as an opportunity to “correct stereotypes”.’

Correct sterotypes; or replace them with new, improved (but in the end just as false) stereotypes?

To misquote someone, “Meet the new stereotype – so as the old one”.

Is that a modern “the King is dead, long live the King!”?

How dare you misquote Pete! LOL

David, there is no doubt Pascoe tells a great story, laced with excellent references that make it substantive. It is bullshit to suggest that there are problems that require revision. In the same way that science starts with hypothesis and there is no revision, there is further interrogation and substantiation. In that Pascoe has done us proud. From his work we grow, from your article we shrink.

Science starts with observation and hypothesis and then sets out to prove or disprove the hypothesis via testing…if testing results in disproof, a new or amended hypothesis is required, followed by more testing…

If Dark Emu claims to be an accurate reference, it apparently requires an errata, since it lacks evidence for its hypotheses. If it is classed as a story, it does not.

FoolMeOnceSOMFMTSOY, thank you for the lesson, “science” is? process! I was intrigued by Dark Emu and read it as a story, I learned, I explored further, I learned more. Pascoe sent me on a journey. Dark Emu did not strike me as a scientific thesis to be defended, so apologies if you misconstrued my reference to science. As an undergraduate Geologist, I questioned the hypothesis that the earths core comprises essentially of iron. Some long bows are drawn to hold this “scientific” position. longer bows are drawn to shoehorn indigenous history into a mold shaped by historians with prejudiced perspectives. Some of the best paradigm shifts come from revisiting hoary old chestnuts. I thank Pascoe for doing this to the established world view of the original people of this continent. What he does so beautifully is lift the observations from some of the documents of the early invaders. What better way of shaking the foundation of established dogma than to show the duality of the original “observation” as per your scientific process leading to hypothesis “x” about the early inhabitants of this continent. I also did not connect with Dark Emu claiming to be an accurate reference, you may be able to help me with that, if you hold that to be true.

Is it not sufficient to suggest that elements of an indigenous community conducted themselves in a way that was equally as astounding as that of the ancient people of Mesopotamia, without having to assume that these characteristics were uniform and pervasive. I think the researchers in this field are going to have to pull their socks up and conduct some good science to deal with the observations alluded to by Pascoe. Ad hominem attack of Pascoe is just laziness, or possibly worse.

No Stan, it’s not about the myth. Not for me anyway. It’s about information. And I was glad to have more via Pascoe’s book, even if I took it with a grain of salt, as I do with most I read, even those who are impressive like Sutton and Walshe.

Stan is a constant disappointment.

Maybe we might ‘bank’ Pascoe’s storyline temporarily and consider David’s point that Gammage sold 50,000 copies and Pascoe 250,000? A demonstration, Walsh says, of it’s “enormous appeal to progressive white folk.”

It seems white folk particularly, are the real drivers of Pascoe’s work. Why? Why progressive? Could it be more guilt? Or desire to associate with being opposed to an American, utterly racist cascade of white generated hate? Or, as Grant says . . . “Australians have bought Dark Emu because they want the myth . . .”

There can be no doubt that the metropolitan voice of Australia over recent times has focussed upon, and reacted to, the growing indigenous claim for justice. Heritage and leadership melded bound to appeal. But unity, one Australia, much more problematic?