This is the name of a new academic paper (still in working form) that Aaron Martin and Dr. Juliet Pietsch are currently writing – and they were extraordinarily kind enough to let us have a little bit of a peek before it gets published. The abstract of the paper lays out the broad contents and purpose:

This paper examines to what extent older and younger generations of Australians contribute to or disrupt the stability of the Australian party system. The Australian and international literature would lead us to expect that older generations contribute to the stability of the party system in a number of ways: by being less likely to vote for minor parties, having a stronger partisan identification and being socialised into a voting pattern at an early age. Using data from the Australian Electoral Study this paper will test these expectations by looking at generational effects. In doing so we find that older Australians contribute to the stability of the Australian party system by being less likely to vote for a minor party and being more likely to vote for the same party over time. We also find that young people have a weaker partisan identification and enter the electorate less likely to vote along parental lines. Controlling for a variety of factors we find that generational factors are strong predictors of voter volatility.

While that is extremely interesting in and of itself (and it really is, the research is a cracker!), where the paper really pounds into the pointy end of modern electoral politics is through their analysis of intergenerational voting behaviour.

One of the themes we regularly explore here on the blog is the notion of the Coalition’s Demographic Train Wreck – how historically the Coalition have received a premium level of voteshare from the generation born before World War 2 (that we call Gen Blue), how that vote has delivered them electoral benefits for over 30 years – but it hasn’t been replaced in the following generations, leading to a structural decline in the Coalitions vote as this older generation continues to become a smaller proportion of the total electorate. Our most recent piece on this can be seen over here.

Our work on this topic was largely derived from the excellent research undertaken by Ian Watson (whose historical age-cohort Newspoll data we use regularly). The most recent update of his paper, “Is demography moving against the Coalition? Age and the conservative vote in Australia, 1987 to 2007” can be found on his site.

The Grey Vote: Ageing and Cohort Succession adds a new dimension to this argument by not only using the Australian Election Study to track the primary vote of 4 generations of Australian voters (Depression Era/Boomers/X and Y) since 1967, but also delves into issues of partisan identification over time, increasing minor party vote levels, the declining influence of parental voting patterns on a persons vote and how this all washes into the potential for future electoral volatility.

With permission (aren’t they just fabulous), we can have a look at how some of this is playing out. The first thing to note here is that the data comes from the Australian Election Study – which is a large post-election poll undertaken in the weeks and months after every Federal election. The one problem that the AES has though, is that it tends to slightly inflate the vote for the party that won the election, and slightly deflates the results of the major party that lost – but only by a few points at most. In some respects, this is almost unavoidable as it’s an extremely common occurrence for these types of “post event” polls and goes to the psychology of a small proportion of the public either liking to be on the winning side, or not recalling their actions and simply going with the majority.

So saying, the patterns involved here are consistent across both time and differing political flavours of government administrations – so the trends are robust.

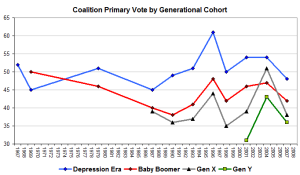

First up, using the data in the paper, we’ll track the four generations of voting behaviour for the Coalition primary vote. (just click to expand the charts)

As we can see, those born in the Depression Era have a consistent and considerable pro-Coalition voting disposition compared to any other generation. Also worth mentioning is how each subsequent generation consistently votes for the Coalition at smaller rates – with Depression Era being strongest for the Coalition, followed by the Boomers, followed by Gen X and Gen Y coming in weakest.

You might notice that the Gen X result in 2004 appears to be unusual? That’s because it is – I have it on good authority from multiple sources that the Gen X primary vote for the Coalition in 2004 is about 7 points overcooked in the Australian Election Study compared to what actually happened. However, don’t let that detract from the rest of the data – having one outlier of this magnitude isn’t statistically unexpected in a set of 32 observations in a post-event style poll.

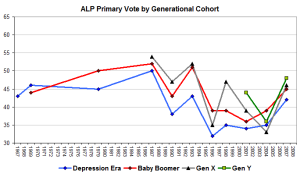

If we now move on to the ALP primary vote:

What we see is that the only generation that votes in a consistently different manner to the others here is the same Depression Era cohort – voting in smaller proportions for the ALP than any other cohort at every election (including the 2004 election once we take into account the outlier nature of the Gen X 2004 result). Boomers, Gen X and Gen Y however all seem to broadly move together, and at the same rate for the ALP over the last 20 years.

What we have started to see, and expect to continue to see at an increasing rate in the future, is the national primary vote of the Coalition losing the premium that the Depression Era voters have historically delivered them – as the Depression Era generation becomes a smaller proportion of the electorate – resulting in a national primary vote that increasingly approaches the average value of the other 3 generational cohorts.

How important is that Depression Era premium vote worth for the Coalition?….. I hear you ask.

Well, if the Depression Era vote was removed from recent election results, Howard would have lost in 1998, lost in 2001 and have been line ball in 2004 – it’s the most electorally significant demographic for the Coalition and one whose electoral power isn’t being replaced in other generations naturally – meaning the Coalition will have to attempt to replace the natural vote boost they receive from their Depression Era voters with other generations, deliberately via some political strategy, should they wish to be regularly in government again in the future.

The way the demographics are changing doesn’t mean that the Coalition will never be in government again – but rather, that without solid generational repositioning they will far more times than not, find themselves in opposition. Ultimately, however, their electoral future is in their own hands.

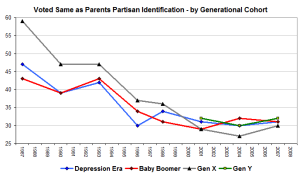

The non-replacement of the Coalition vote premium links us in to another fascinating phenomenon that Pietsch and Martin unearthed in their research – the way that the partisan identification of ones parents is having decreasing influence across time on any given person’s vote.

The Australian Election Study asks:

“Did your father have any particular preference for one of the political parties when you were young, say about 14 years old? And what about your mother?”

When the responses are combined and compared against how the respondent actually voted in any given election, and then broken down by age cohort, we get a clear trend among all 4 cohorts:

Only a tad over 30% of the population now vote according to the partisan identification of their parents and it’s been flat for 3 elections now. It’s as if we’ve entered a relatively new post-parental partisan voting era that is being manifest in all generational cohorts.

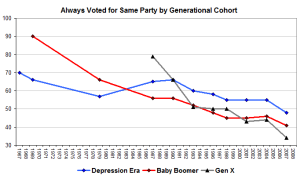

In the literature, one of the best (historically at least) predictors of the way a person will vote is the way their parents have voted in the past – yet here we see this relationship effectively breaking down in Australia. Also worth mentioning here is another piece of related data unearthed in the paper – the proportion of respondents that have always voted for the same party (although this time, we’ll leave Gen Y out since they havent been voting for long).

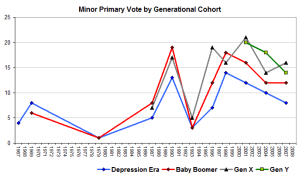

Rather than this breakdown being caused by children all voting for the major party opposite to their parents, or people always voting for a major party – a significant proportion have been giving their vote to minor parties. Pietsch and Martin also tracked the generational minor party voting patterns across time.

What stands out is not only how the Depression Era generation have the lowest rate of minor party voting, but how – generally – the younger a person is the more likely they are to vote for a minor party.

With a structurally declining Coalition vote, a quite variable ALP vote and an increasing minor party vote, there is a growing potential for volatility and decreasing political stability in two party government terms as we head into the future if these trends maintain themselves. That is a topic that the paper explores in some depth and is well worth reading.

The other serious issue the paper explores is the robustness of these generational effects through some quite clever multivariate regression models that control for other variables such as income and education. They find statistically significant generational effects with the Coalition and Minor Party vote.

As it’s still a working paper, it’s not yet ready for publishing – so a big thanks goes out to Aaron and Juliet for allowing us to have a sneak peek at what the paper will contain. When it eventually gets published sometime over the next 9-12 months or so, we’ve been promised a copy so you can all have a read – it will be worth the wait… it’s an absolute cracker.

Crikey is committed to hosting lively discussions. Help us keep the conversation useful, interesting and welcoming. We aim to publish comments quickly in the interest of promoting robust conversation, but we’re a small team and we deploy filters to protect against legal risk. Occasionally your comment may be held up while we review, but we’re working as fast as we can to keep the conversation rolling.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please subscribe to leave a comment.

The Crikey comment section is members-only content. Please login to leave a comment.