The fragile stability that has characterised politics in Timor-Leste — Asia’s newest democracy — for the past two years is set to be shattered after Tuesday’s presidential election, and red flags will be raised in Canberra.

Nobel laureate and former prime minister José Ramos-Horta, 72, has opened up an unbeatable lead over incumbent Francisco “Lu’Olo” Guterres, with about 60% versus 40% of the vote during Tuesday night counting in the second-round runoff for the country’s presidency.

In the lead-up to the first round of the elections, where 16 candidates competed for votes, he promised an “earthquake” in the country’s politics — before winning 45.6% of the vote compared with Guterres’ 22.1%. But candidates from a range of minor parties fell in behind Lu’Olo, leading to a result that’s likely to be closer than many observers expected. Observers in the capital Dili told Crikey that turnout was notably lower than in the first round.

Under the country’s hybrid presidential/parliamentary system, the president can officially engage political leaders in an effort to reach — or even change — a governing alliance among two major and a handful of minor parties when an overall majority is rarely attained. They can also force an early election if such talks are unproductive.

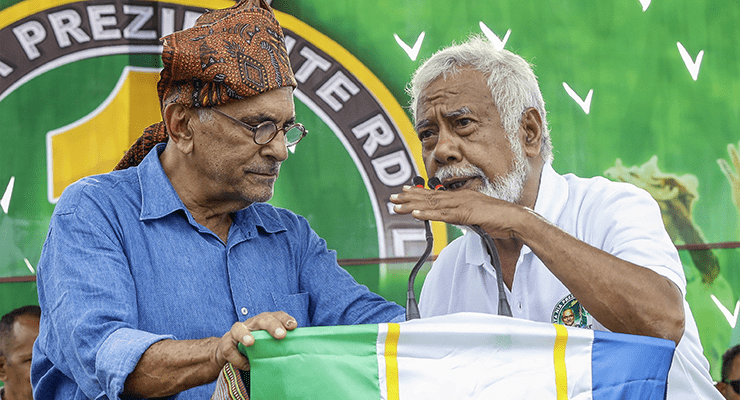

Ramos-Horta’s candidacy was backed by independence hero Xanana Gusmão, 75, a former president and prime minister who remains the nation’s most influential — yet often divisive — figure.

Observers see Gusmão’s move as the first step in an attempt to claw back either the prime ministership or a majority position for his Congress for the Reconstruction of Timor (CNRT) party. Gusmão has described the current parliamentary government — which is elected separately — as “constitutionally illegitimate”. This is because Lu’Olo refused to swear in nine CNRT ministers after the 2018 elections due to ongoing investigations into corruption, as well as other issues that set off instability that fomented change in the ruling alliance and fresh elections in 2020 where the CNRT was sidelined.

Ramos-Horta’s win is also likely to increase pressure on Fretilin, at present the biggest party in the ruling parliamentary majority. It governs with an alliance of three smaller parties, including the People’s Liberation Party headed by Prime Minister Taur Matan Ruak.

Like most other parties in the country, Fretilin is still run by a veteran from the battle for independence that took place between two and four decades ago. Mari Alkatiri is also a former prime minister, but observers have said his position is under threat from Rui Maria de Araújo, another former prime minister, who leads a faction that believes the party has atrophied somewhat in recent years.

Ramos-Horta was the nation’s second president from 2007-12 after a short stint as prime minister (2006-07). He was foreign minister from 2002-06 and won the 1996 Nobel peace prize along with Catholic Bishop Carlos Belo, who later retired and left the country, citing ill health. Fretilin blames Ramos-Horta for a bloody crisis during his time as PM in 2006 when dozens were killed in politically motivated street fighting in Dili.

The latest ructions in Timorese politics are certain to cause consternation for the Morrison government in light of China’s continuing push into the Pacific — and ever closer to Australia. This has been underscored by the security pact it has signed with the Solomon Islands, officially acknowledged by Chinese state media and Solomon’s Foreign Affairs Minister Jeremiah Manele.

Closer to home, a Chinese company plans to construct a major fishing port in Papua New Guinea, and Beijing has drawn close to other Pacific Island nations, including Vanuatu. There are rising concerns about parts of Beijing’s world-leading fishing fleet acting as a seagoing militia.

At the heart of concerns of Australian diplomats and security officials concerning Timor-Leste is Gusmão’s endgame: the resumption of spending and work on grand plans for the $18 billion Tasi Mane project linked to the Greater Sunrise oil and gas field in the Timor Sea.

The project would see onshore gas processing constructed on Timor-Leste’s remote south coast — the capital Dili, second city Baucau and other major settlements are all on the country’s north coast. The project includes a major port and an airport.

It has been Gusmão’s pet project since 2007, his solution to securing future energy revenue for when its reserves run out. Energy revenues are Timor-Leste’s only significant national income. They are tipped into the Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund, a sovereign wealth fund tapped each year for the budget. It is expected to run dry within 15 to 20 years, and in the interim the nation must create industries and/or expand its energy activities.

But attempts at funding the Tasi Mane project via the investment of global petrochemical companies have proven difficult, and China is seen as something of a white knight by some in Dili.

China and Timor-Leste have been friendly since before the latter gained independence from Indonesia in 2000. China has privy aid to build some infrastructure, including a major hospital and patrol boats, and Timor-Leste has maintained an embassy in Beijing. Chinese naval ships have also been welcomed to Dili.

In 2019 Ramos-Horta was appointed to the board of China’s signature Belt and Road Initiative and welcomed Chinese investment. Gusmão has made numerous trips to Beijing, at least once playing up to his hosts by dressing in garish Chinese livery.

Gusmão has also slammed as an “insult” to Timor-Leste the ongoing secret trial of Australian lawyer Bernard Collaery who — together with a former Australian security official — exposed the Australian government spying on the Timor-Leste cabinet in 2004.

Still, many observers believe that fears about Timor-Leste by the increasingly Sinophobic security and diplomatic apparatus in Australia are overblown. But it will be scarred after dropping the ball so comprehensively on the Solomon Islands.

Thanks in part to the Australian government East Timor continues as the world’s poorest nation. We even did nothing when the Indonesian army murdered our very own journalists up there, in fact Canberra tried to cover it up. (The Balibo 5). We trample on our smaller neighbours, waving the big stick, as though we think we’re something special and they aren’t. Their lack of numbers, land area and GDP does not mean they are unworthy of respect.

Australia could give every household on every Pacific and Indian Ocean island renewable electricity, for example. (Without putting ‘A gift from Australia’ stickers all over it). Cancelling one submarine would pay for it all. It would do us all a favour – or is that not what Canberra is for?

Are you advocating what’s called a bribe in other circumstances?

Oh the irony! A Sovereign nation, that we dared to spy upon, has decided that we can’t be trusted and prefers someone else? Our “backyard” is not “ours” and Sovereign nations are quite entitled to enter into whatever arrangements and alliances they so desire in terms of their respective National Interests.

Did we really expect Timor-Lester to trust us after Witness K/Bernard Collaery? If so, the members of the Morriscum Government are even bigger fools than we already think they are!

Never stand between our government and one dollar.

What we need to do is appoint Lord Downer of Baghdad special envoy and have Zed Seselja accompany him as ‘influencer of note’ and whisk them over there posthaste in order to make Australia’s views very clear – whatever they are. Unfortunately David Irvine and Ashton Calvert are not about to accompany them to add some sort of weight to the delegation. On top of the Solomons debacle this one just about takes the cake

Former Vic Premier Steve Bracks has been doing pro bono advocacy for Timor Leste since 2007.

Would be interesting to learn his views on Australian policies and actions on (& against) Timor Leste; presumably different from the LNP government and former Ministers?

I presume that Zed, the Fixer, has already been put on notice to express, post election, his Government’s disquiet about any Timor L’Este – China bromance in the offing. After the LNP’s Timor-L’Este Cabinet Office bugging episode which has been on ever-extended seasons in our Courts courtesy of the LNP and their Nelson-ion acquiescence to the sale of the Port of Darwin to Chinese interests citizens of Timor-L’Este could be forgiven for being even more confused than our current bunch of LNP party hacks obviously are.

Should the LNP actually be a little agitated about the possibility of a Chinese naval base in Honiara we should start lining the walls, floor and ceiling of our Federal Cabinet Room with the best quality innerspring mattresses suitable for long naps between religiously quiet disengagement seances and mental fog periods of the type the Party is increasingly famous for.

China moving in infers Newtons Law: For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.