Anthony Albanese wants a 5.1% lift in the minimum wage — but how would that affect the economy?

Looking at jobs, inflation and poverty, uncertainty and paradoxes mean there are arguments a motivated person could use for or against.

Effect on jobs

Economics 101 says higher minimum wages will make businesses employ fewer people. The problem in Australia is not enough people have taken economics 201, which says that economics 101 is an oversimplification.

Its logic, though, is appealing: higher labour costs mean firms hire fewer staff. But economics aspires to be a science rather than a system of belief, and the evidence points in the opposite direction to the logic. This evidence is both global and local, industry-wide and industry-specific. It finds no good evidence that higher minimum wages destroy jobs.

For example, what happened to jobs when Sunday trading penalty rates disappeared? The answer is: employment didn’t improve.

“We demonstrate conclusively that the phasing in of wage premium (penalty rate) reductions from 2017 did not impact positively on employment in retail and hospitality sectors,” employment and economic experts Ray Markey and Martin O’Brien wrote in The Sydney Morning Herald last year.

But that’s just one change in one industry. The best work on minimum wages in Australia was done in 2018 by a young man who is now the head of the Reserve Bank’s economics research department, James Bishop. He ran a lot of heavy maths on the history of Fair Work Commission wage increases, and found “that award changes are almost fully passed through to wages, and have no statistically significant effect on hours worked or the job destruction rate”.

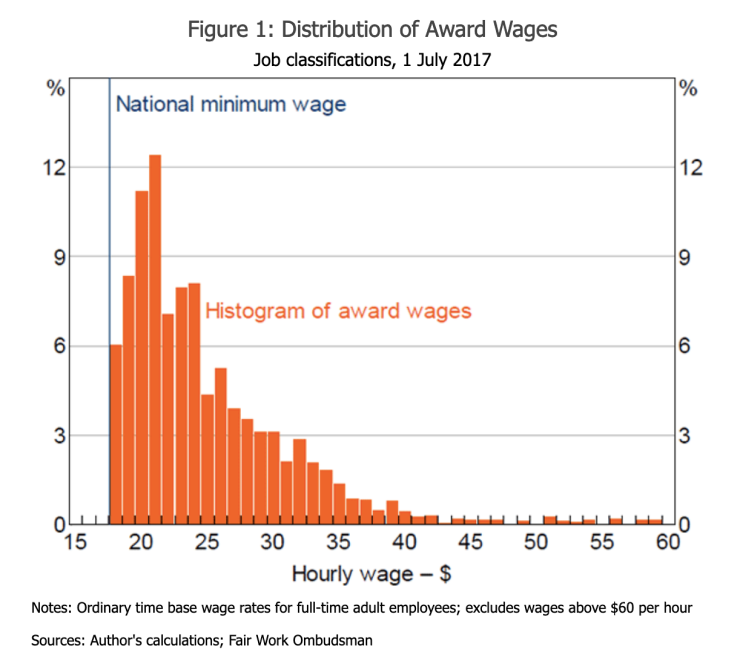

Bishop looked not only at the minimum wage, but all the awards that could be affected by changes in it — of which there are a lot, as the next chart shows. Up to 40% of wages in Australia are affected, directly or indirectly by changes in the minimum wage.

Like all social research, it comes with caveats. The wage rises used as inputs were mostly small, about 2.5%. Bishop says the results ”may not necessarily generalise to large, unanticipated changes in award wages”.

If you wanted to argue against a wage rise of 5.1% you could say Bishop’s evidence doesn’t apply. And you could be right or wrong. Bishop doesn’t specify what counts as “large and unanticipated” because the evidence doesn’t tell us that. It’s uncertain. It’s also possible an effect of minimum wage rises is not destruction of existing jobs but a slowdown in creating jobs. That’s very hard to measure and so also uncertain.

That uncertainty is a characteristic of economic policymaking. Economics is a young science and ultimately a social science. Unlike in physics or chemistry, the rules governing cause and effect are poorly understood and, worse, can change over time. So it is possible to have a result in the real world that contradicts even the absolute best gold-standard evidence.

Just because past wage rises have not destroyed jobs, doesn’t mean wage rises will never destroy jobs. We need to act on the best available evidence, but we need to remain open-minded if and when new evidence appears.

It won’t solve poverty

Cranking up wages won’t solve poverty, because most people in poverty aren’t on wages. Solving poverty is about lifting welfare payments and/or getting people into jobs.

Higher minimum wages might even increase poverty if it reduces job creation, or if welfare payments increase by a fixed amount and higher wages flow through to higher inflation, meaning people on welfare have less buying power.

Which leads us to inflation.

Higher wages have to come from somewhere. For businesses, they need to fund those wage increases by reducing profits or charging higher prices. Profits are good right now, but some increase in prices is likely. The UK finds that prices go up more in months where the minimum wages increases, by 0.08 percentage points.

So what’s the job of the Fair work Commission: to control inflation or raise wages? What matters most? There’s no evidence that raising wages will hurt employment. Is that its priority?

It is not the only policy priority at the moment. We’re in an inflation spiral that the RBA is suddenly working very hard to control. The paradox here is that wage rises both contribute to price inflation and help compensate working households for inflation.

Is it better to have inflation that lasts longer but cuts less deep for wage earners? If you’re a wage earner you probably have a different answer than if you’re on a fixed-payment pension.

Or is it better to have inflation that is briefer, but cuts the buying power of wage earners?

The answer is not given to us by economics; these are questions of values and priorities. It’s great news that Albanese has taken a position on the topic in an election campaign because it lets us use the election campaign to vote for our priorities and values.

The government seems to be alarmed at the potential inflationary impact of an increase to the minimum wage yet neither of the major parties seems to give a stuff about the inflationary effects of the stage 3 tax cuts. Guess inflation is okay as long as already well off people are the beneficiaries.

As I learnt in the accounting ourselves i tried, the purpose of a business is to continue indefinitely into the future – so, not profit

Simplification? Sure, I’m not that educated, but I’ve come across the analogy of the ice cream van with a broken machine – does the owner shut up shop and go home, waste the ice cream? Or does the owner drop his prices, sell.off his ice cream, then go home?

No. 2 is a rather obvious answer. Granted, profit helps you invest more in the business, but when it’s going to sheer $$$ but we’re too poor to give a low end worker an extra dollar an hour

Guess I’ll keep my trap shut I’m only someone who could do with an extra dollar an hour, is $32 a week really that much to be worth?

Why can’t the Fair Work Commission also control profits? Or is that Marxism 101?

if you can’t afford a livable wage for your employees, you don’t have a viable business model If you put prices up to keep your profits and people stop buying your stuff, you either take a cut in profits or close up shop.

With regards to inflation – while of course in part this is because of supply issues, there are plenty of corporations who have raised their prices, but their costs have not gone up by the same amount. Ie they are litterally profiting of inflation, jack up the price because people think that the poor business has to.

A lot of the commentary around the current inflation seems to assume that it is permanent, yet many of the factors may be temporary. Fresh food is affected by extreme weather events. Logistics is affected by (I assume) absenteeism due to Covid infections. Petrol prices are affected by Putin acting like the turd he is. By the way, I don’t own a car and use public transport and I am working from home. Petrol prices do not affect me directly.

Will the sudden jump in the CPI be reversed when fresh food supplies return to something like normal, and truck drivers recover from Covid, and people generally find a way to live with higher petrol prices?

One of the herd of elephants in the room is the price of accommodation, which, as I understand it, is not fully captured by the CPI. I am one of the fortunate who owns a house. I cannot imagine the despair of those trying to rent or buy in the current market. This is entirely down to the current government, its predecessors, and its fellow travelers in the media. Labor proposed some solutions at the last election and got whacked for trying.

By the way, that equation looks simple enough, but meaningless without context and definition of what the variables mean. For myself, I prefer symbols from the Roman/English alphabet. The Greek symbols make it look more exotic than it really is.