What words do you least want to hear from your central banker? “I’m not expecting there to be a recession, but… we’re on a narrow path.” They were spoken by RBA Governor Philip Lowe last month to a conference of central bankers in the global prudential capital of Zurich.

So, how wide is this road?

- There are times when monetary policy is easy and your range of good choices is wide. Like driving a car on a flat road on a dry day, you can drive with one finger or jiggle the steering wheel and both are fine.

- There are times when monetary policy is hard and your range of good choices is very small. Like driving a race car in the rain — you need clear vision, strength and precision timing to avoid a horrible crash.

- There are times when you’re done for no matter what. Like if the semitrailer in the next lane has tipped over and, while you may have a moment to watch it tumble onto the roof of your car, there’s no way to move. You will try to do fast, heroic things but they are in vain: your fate was sealed at a time in the past.

Australia is going to find out whether we are in scenario two or three. The RBA has either a small chance to get things right — or perhaps no chance at all.

Unlike the automotive scenario, where the speed of physics determines the outcome, our situation will be determined by the speed of transmission of monetary policy, which is measured in years. While our fate may be sealed, we have time to talk about it at least. Not least this week, as the RBA today unrolls what is expected to be the second in a series of significant 0.50% rate rises.

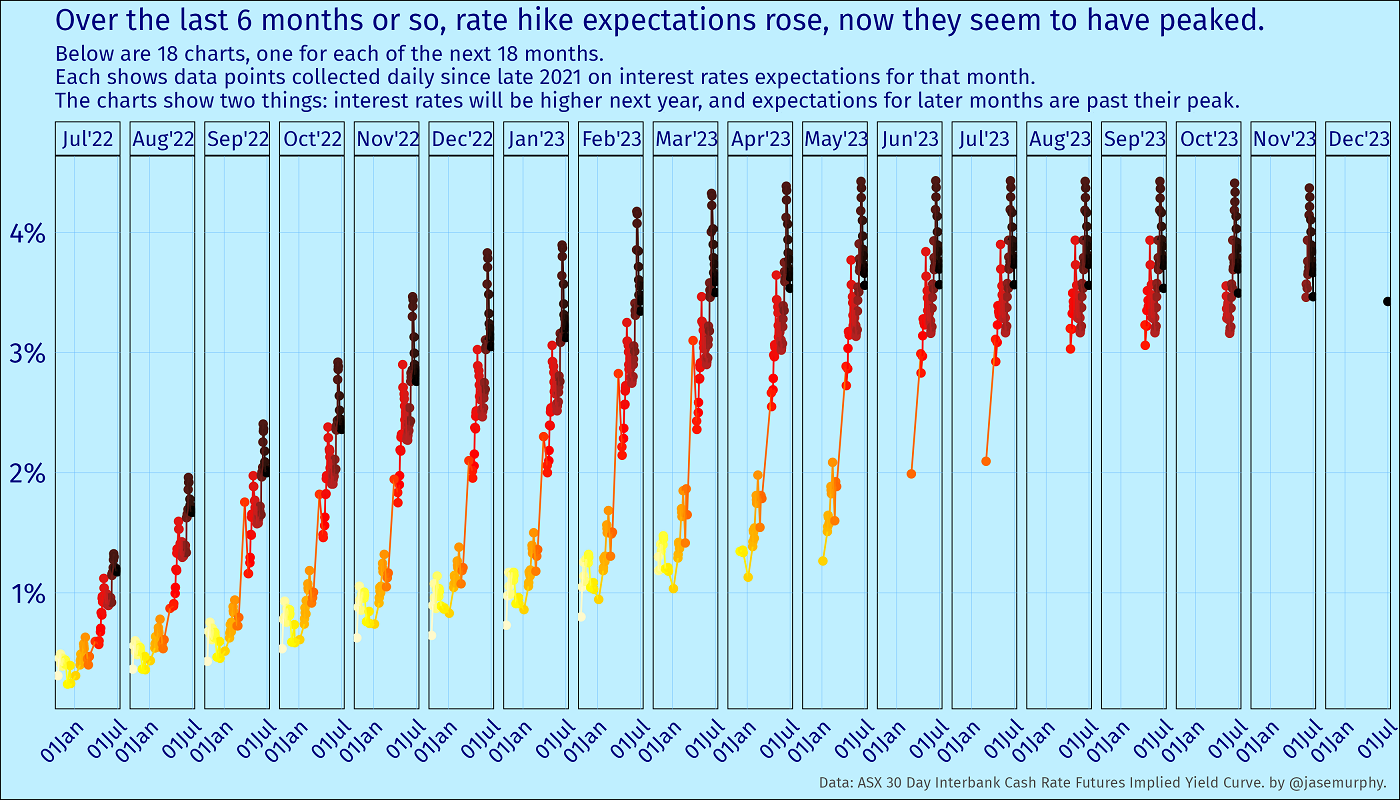

As the next chart shows, interest rate expectations have gone up a lot recently. However, suddenly the pattern is more varied: while expectations for near-term rates are at record highs, expectations for later rates have moderated.

There are two ways to read that: markets think the RBA’s bold action will solve our inflation problem, or markets think the RBA’s bold action will cause other problems. Either way, there won’t be such a need for high interest rates in late 2023, as markets foresaw just a few weeks ago.

How high inflation?

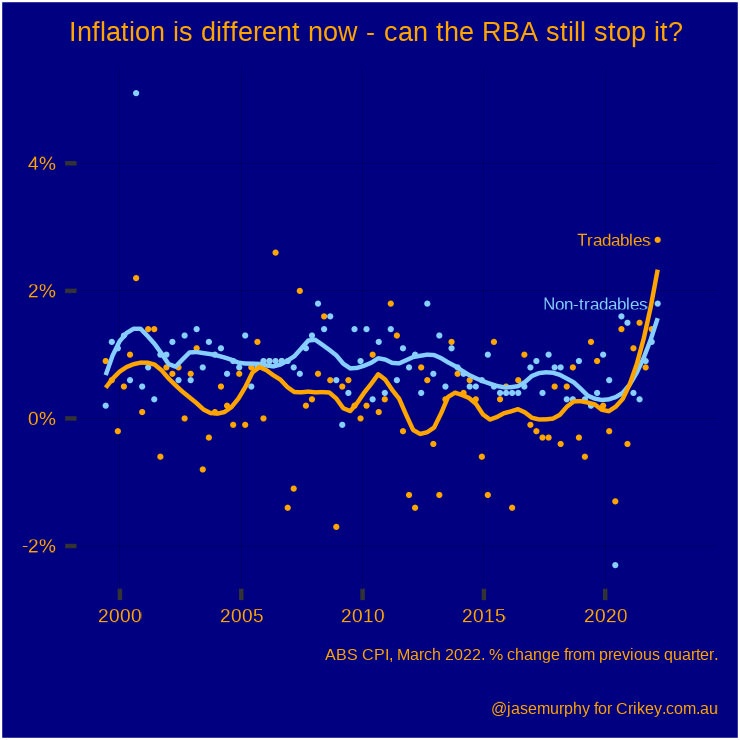

With inflation high and rising, but largely determined by imported goods, the RBA has a dwindling capacity to push back. It may suppress wages, it may suppress rents. But it cannot do much to suppress energy prices nor the prices of manufactured goods, such as food, computer chips, cars, etc. Note that it doesn’t matter if these things come from overseas or go overseas. Tradeable goods are just those that have their price set in global markets.

As the next chart shows, we are used to inflation in tradeable goods being low — scarcely above zero each quarter. Now it is very high.

“Global supply chains are long and complex and it turns out if there is a problem anywhere in the chain then it reverberates right through the system and keeps putting prices up,” said Lowe at that same conference. “We’re still getting price pressures from supply chain disruptions.”

We can make our dollar stronger by raising rates — in theory anyway — and that strength makes imports a little cheaper. But when every other central bank is also hiking, we are really just running to stand still. And with all that running we could do ourself a mischief.

The big risk is interest rates rise enough to squash the economy, reverse employment growth, and make our current flirtartion with full employment a distant memory of what might have been — and yet that is not enough to quell a rising consumer price index. And then there’s housing.

The national obsession

“I presume housing prices are going to adjust further downwards, so that’s another dynamic affecting household balance sheets,” said Lowe.

Consumer confidence is already plumbing depths Jules Verne scarcely conceived of, and the house price falls have only just begun. Once the rot sets in — and most big banks think it will be a one- or two-year reversal — Australian household perceptions of their own wellbeing could get pessimistic indeed, with consequences for retail spending and the jobs retail spending props up.

The RBA is in a heck of a tight spot. It needs to make a lot of people unhappy on the way to squashing inflation. We may hope inflation proves soft and yielding and the pain is brief.

The driving-a-car metaphor would be improved if we also specify the driver is facing backwards and can only see out the rear window, and is steering the car by holding one end of a big bungee cord whose other end is clipped to the steering wheel.

I may have to steal that analogy – it’s beautiful, and perfectly describes half the problem with most central bank actions.

The other half, of course, is that they have no idea what actually /causes/ inflation unless it’s really obvious (like it is now), nor how their preferred actions (interest rate changes) actually effect inflation, or even what the broad direction of the effect is at any given point in time. Which makes their bungee cord on the steering wheel even more laughable, in that “I’m laughing hysterically because if I start sobbing I’ll never stop” kind of way.

the other thing is they only talk to people who have the same view, us plebs don’t get to give our wisdom. Their wages ‘research’ involved talking to 63 business owners / groups and zero worker representatives

All this inflation crisis is demonstrating is that economists never know what’s going on but sprout macro and monetary advice anyway under maxims that sound wise but have all be proven to be compete nonsense. Is it not obvious that inflation is being dominantly caused by global issue over which neither we nor the RBA have any control at all. So the increase in interests rates is clearly going to exacerbate inflation, not dampen demand. So why pull that lever?

been – inflation is a monetary thing, they target 3 percent as part of monetary policy

Jacking up interest rates is a very blunt interest rates is a very blunt instruments. Why hit demand so hard? We may finish up just as badly as in 1982 and 1991.

Since 2008 the reserve bank has been using MMT to pump prime the Australian econom, this information is available for all to see. This and ulta low interests rates ended with excess inflation it has to, The reserve bank has a policy target inflation of 3 percent so it is in excess of targeted . The real question is why cant we have a target of 0 percent. Money printing is inflation.Some say we need some inflation to keep rolling over debt.

This and ulta low interest rates = price inflation plus asset inflation

Asset inflation i.e your house is not in the CPI as the C means consumer and assets are capital

So this problem was made by a system that has inflation as a core component of it,its called FIAT money.

This cycle of boom and bust gets closer closer as the Reserve over adjusts and over stimulates out off sequence.

simply put the reserve is unelected, unaccountable people

If the RBA was following the recommendations of most MMT informed economists they’d have set the cash rate at 0 and would have either told the Treasury to stop issuing bonds at all, or would just be buying them all up as soon as they were issued (if for some reason Treasury wasn’t following MMT recommendations but the RBA was). MMT has a lot more to say about government spending than it does about any of that, though, since in the MMT understanding of how economies work government spending is far more important than what the central bank does (as long as they’re doing their core business of making payments as instructed by the government).

Regarding the rest of your argument, if ultra low interest rates automatically lead to high inflation, why did we just spend ten years with record low interest rates and inflation below the RBA’s target band? And why did inflation only kick off like this when we saw /supply side/ issues as a result of the pandemic and then a war? And why did it only really kick off /after/ the RBA stopped “money printing”?

You’re not wrong that the RBA is full of unelected and unaccountable people, but it’s hard to see how any of your other ideas match up with reality.

Very pretty graphs but nothing to answer the question – “why are economists fed?”

Now now, everyone deserves to basics required to live a decent life, even economists. The question we should really be asking is why anyone listens to them.

A definition of waste is a coach of economists going over a cliff with some vacant seats which could have been filled with lawyers.