Channel 10 describes its new show, Hunted, as “Australia’s real-life game of cat and mouse”. Fun, right? But while this thinly veiled copaganda may portray digital surveillance as all fun and games, the reality of these technologies and those with the power to use them is anything but entertaining.

The show follows nine pairs of Australians — the “fugitives” — tasked with evading capture by the “hunters” for 21 days. The hunters have extensive experience in the Australian Police Force, the military, security and intelligence, and they use a range of digital surveillance tactics to track down the contestants. The show’s second episode surpassed 1 million viewers across Australia, giving Channel 10 a rare ratings win. The next episode is on tonight.

The head of intelligence for the hunters, Ben Owen, describes himself as a “big privacy advocate”. He told The Sydney Morning Herald he expected that viewers of the show “who have nothing to hide will feel comforted”, while “those on the wrong side of the law might start changing their passwords, look at multifactorial authentication and start chucking their phones in the river”.

We all have something to fear from increased surveillance, regardless if we have something to hide, and what is considered to be the “wrong” side of the law is determined by those in power. We need only look to the criminalisation of protest across Australia, or the fall of Roe v Wade in the US, to consider the arbitrary nature of criminality. By design, surveillance is about control, and a real “big privacy advocate” wouldn’t be so quick to dismiss how much it’s creeping into every aspect of our lives, nor the merit of practising good digital security.

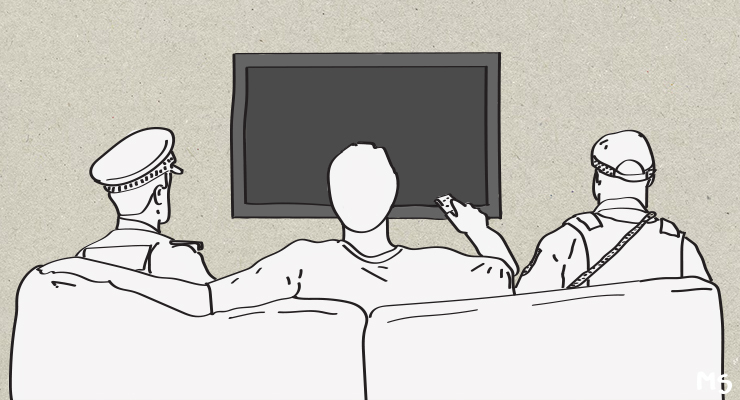

This incongruity is reflected in the show itself, which simultaneously glorifies law enforcement’s use of digital surveillance while also portraying it as a harmless, playful game. From the outset, the show frames the hunters’ techniques as similar to those used to apprehend terrorists, priming us to accept the justification for such invasive measures and to assume that we would never become real-life targets.

Shortly afterwards, a pair of white women laugh that they “couldn’t think of a better adventure than literally running from law enforcement”, demonstrating a truly stunning lack of awareness of how, for many people, interactions with police are characterised by trauma and violence. If your experience of police is that they are helpful rather than threatening, it might not occur to you that they often use their powers against vulnerable people rather than to protect them.

While technically a “reality” show, Hunted is so over-produced that it crosses into the realm of the unreal. This is made worse by how obvious many of the digital surveillance techniques are simulated. For instance, given that Channel 10 can’t actually access CCTV footage (thank goodness), it has instead had to hack together a workaround using Go-Pros. It’s pretty evident after reading through #HuntedAU on Twitter that some viewers perceive the surveillance tactics portrayed on the show to be ridiculous or unbelievable.

What we are left with is an unrealistic show portraying a warped vision of the terrifying reality of unchecked surveillance power. Watching Hunted as a privacy and anti-surveillance advocate, I felt like I was looking at society through a deeply cursed funhouse mirror. What’s troubling is the possibility that viewers may be swayed to underestimate or dismiss the real-world dangers of digital surveillance and the legal powers that enable its use (read: abuse).

Take, for example, the Surveillance Legislation Amendment (Identify and Disrupt) Act. This law provides extraordinary hacking and surveillance powers to law enforcement, including the ability to add, copy and delete data from devices, access entire networks, and take control of online accounts. It was widely criticised as going beyond what is necessary, and lacking appropriate safeguards to protect our democracy and human rights.

On top of this are powers contained in the Telecommunications and Other Legislation (Assistance and Access) Act. This highly controversial anti-encryption legislation enables security agencies to force tech services to bypass security and privacy protections. These extremely invasive powers, coupled with a lack of federal protections for human rights, leave people in Australia especially vulnerable to the harmful impacts of surveillance on an individual, community and societal level. We have already seen how powers of surveillance have been weaponised against activists, journalists and whistleblowers.

There are plenty of reasons we shouldn’t trust law enforcement with such invasive technologies, including the many examples of how it abuse its power. Recall that time police “accidentally” handed over 11 years’ worth of phone data to a woman’s abuser. Or the time a police officer accessed a computer system, leaked the address of a victim-survivor to her violent former partner, and then had his conviction overturned.

Broadly, the purpose of surveillance is to discipline, control and change our behaviour. In real life, surveillance is a highly efficient way to enforce social order — it encourages us to conform and creates a punitive culture of compliance. In Hunted, the feeling of always being watched results in many contestants commenting on how they constantly feel anxious, panicked and paranoid. We should never underestimate the chilling effects this has on our democracy and on our ability to hold those in power accountable.

If you squint really hard, perhaps this instance of mainstream television offers the Australian public a teachable moment: raising awareness of the volume of data we emit, the myriad ways those in power can leverage digital technologies to track, control and punish people, and the importance of strong privacy protections and good digital security. Unfortunately, that message is yet to come through.

A few people have asked what I would do to “win” Hunted. But the problem is that when it comes to surveillance, the game is rigged. The state has a monopoly on violence and uses surveillance to wield its control. As long as these surveillance powers continue to go unchecked, no matter who wins the show, we all lose the game.

I remember a particularly dark Science Fiction short story from (at least) 30 years ago that used an almost identical scenario to this “reality” show…………..

………except that the Hunters took the heads of the victims as trophies and competed for who could take the most heads. An added twist was that they also hunted each other, and a Hunter who killed another “inherited” his head collection.

Perhaps that will be reserved for series two…………………..

Thanks for that. There have been a few black dystopias in science fiction that foreshadow this. I remember one by Australian Frank Roberts called It Could Be You. It was a riff on an existing, I think, radio show. Throughout the day clues as to who you was were broadcast, slowly narrowing it down. Citizens all had a company knife that could be used to kill the victim for a big prize when the clues got the the person singled out, at which point the cameras would zoom in… A world of commercially profitable daily induced stress for everyone followed by relief and the thrill of the pile-on. A solid form of social conditioning. Though the Chinese are probably doing it better in the real world with their social credit system.

Yes, I find this harassment dressed up as entertainment disturbing. What about the fears engendered in innocent bystanders while helicopters and these pumped-up operatives thunder through their lives? Or arrive at your front door demanding entry, forcing their way into your home, and subjecting you to interrogation?

Hunted – the Channel 10 reality show is like watching a day of surveillance in Australian cities in 20 years.

Although most Australians are horrified by the way the Chinese government surveillance it’s citizens – Australia is quickly following along in its wake.

We no longer are a free Democracy!

What’s worse is we’re treating it as entertainment. How long before the boredom threshold sets in and we start ‘hunting’ real people like animal rights activists, Extinction Rebellion members, or refugees who’ve outstayed their visas?

‘They came for the Jews, but I said nothing because I wasn’t a Jew. They came for the . . . (etc)’. The history of the 1930’s shows that the descent into barbarism happens very quickly.

When they said the price of liberty was eternal vigilance, the Panopticon was … not what they were thinking of

This is the first time I’ve seen a program like this get called out for what it really is – well done. Let’s hope similar-ish programs like Border Security, Highway Patrol, SAS Australia etc get called out for what they are as well – and/or have more programs providing an alternative perspective.