Someone tweeted on Twitter on the weekend about the Voice, something to the effect that while they will be happy to hear opinions from First Nations peoples about the future of the proposal, they’re much less interesting in hearing from professional columnists and opinionistas. Yeah, uh, sorry, too late. The Voice is out of the box now, on the road to referendum, and the plain fact is that it is now a question for everyone.

The very act of taking this to a referendum makes it a general transformation of the way we are constituted as a state and a people. Autonomous political action, from starting a party to a tent embassy to unilateral declarations of sovereignty — yep, sure. No one else should give views or helpful advice unless invited. But if this thing is going to get up, then about 96% of the votes it needs are going to be non-First Nations (NFN hereafter). This is one of the many paradoxes of this push — the moment it was committed to referendum, by sheer weight of numbers, it instantly becomes an NFN thing, and a state object to boot.

This has started to become apparent to increasing numbers of people, as the machinery of referendum becomes visible — and we remember just how awful it is. As a country we basically gave up on referendums after the Hawke government’s disastrous run, when Labor lost heavily in 1984 on a grand plan to allow federal and state governments to exchange powers by agreement, and in 1988 when it presented a four-bill referendum that looked administrative but which was also overreach (four-year matched House-Senate terms, local government recognition, religious freedom and codified rights), and that was it — apart from John Howard’s 1999 republic trap, which took down the preamble question with it.

The “preamble” disaster really killed the referendum as a mechanism of political change. The text honouring First Nations peoples was anodyne enough, but a lot of people voted against it on grounds of division. It had been wrapped in shoutouts to immigrants and servicepeople, so a bunch of people on the left voted against it because it was so diluted.

Thus ended, till now, our terrible history with referendums. People talk about there being eight out of 44 “yes” votes, and one progressive “no” vote. As I’ve noted before, it’s nothing like that good. Five of the eight “yes” votes were almost totally procedural. One, on state debt in 1910, was significant in changing federal-state relations. Another, in 1946, on social services, was a much-reduced version of John Curtin’s failed 1944 attempt to create sufficient federal power for a “new deal” government.

The progressive “no” vote was the rejection of Menzies’ attempted criminalisation of the Communist Party. That leaves 1967, identified in history as our great belated civil rights move, with a 90% “yes” vote. There was a spirit of that underneath it. But it was also an administrative vote too. The sole affirmatively progressive/radical and comprehensive shift we voted up was in 1946, when we gave the federal government the power to make a welfare state without its measures being struck down by the High Court.

The talk is that the challenge to amend the constitution is difficult. It’s not. The US constitution is difficult to amend. Ours is virtually impossible. Both were designed that way. Amending the US constitution (almost) always starts in Congress (with a two-thirds majority), and is then ratified by state legislatures (with a three-quarters majority). Though the people never get a look in, it’s designed to have some malleability; both the Bill of Rights and the post-Civil War “reconstruction amendments” essentially changed the notion of equality and rights underpinning the state. The whole thing was, after all, created by enlightenment intellectuals dodging up a revolution out of a few imposed taxes, to give History a nudge. Our constitution is a different beast, written to hold in place a federated post-colony of a nation-empire constituted by race, custom and unwritten convention, a constitution short on abstract rights, long on binding administration.

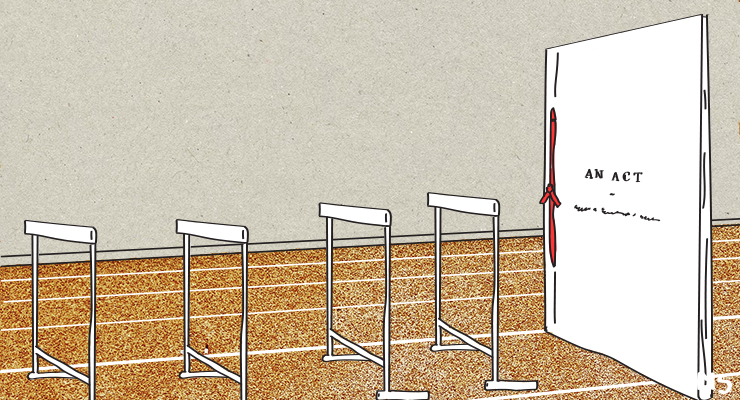

Arguably, the referendum provision is not there as a change agent but as a safety valve, allowing change to occur only when it absolutely must, to resolve absurdities, or vast gaps between letter and public sentiment. Section 128, the referendum section, leaves a gap of two to six months between proposing the constitutional change (as a law in Parliament) and the referendum vote itself. That is obviously designed to stress-test the proposal, if it hasn’t already started well beforehand.

It has started well beforehand, and the stresses are already beginning to show. The government’s commitment to the Voice was announced, with a minimal-detail proposition, at the Garma Festival, to more of the lathering national self-congratulation we have come to expect with anything to do with the Uluru Statement from the Heart, or the Voice. Then the questions began about the detail, some from the querulous right, some not. Then the pro-Voice right slapped the anti-Voice right down. Then some suggested that the Voice proposal was going to need to be detailed to win; others that it must be general, to be filled out later by Parliament.

This all happened in the first four days. There are two years of this to go. Quite aside from this, there is an intertwined campaign to remove the “race powers” from the constitution, which, if they are raised in conjunction with the Voice, will confuse more than 90.77% of voters from the get-go.

The clouding of the skies over Garma was blamed on those who wanted to destroy the Voice proposal. Well, maybe, maybe not, but so what? The same questions are going to be asked when the campaign goes to 18 million voters. The referendum process is doing its work, to reveal the nature of the proposal, and what it is revealing is that, strategically, this is the worst proposal that has ever been taken to the referendum process.

The Voice is neither a simple principle nor a self-contained, clearly defined new institution; it asks the people to decide, then tells them to hand over all the crucial decisions to Parliament. At the heart of it is an entity that, it is claimed, is essential to close the gap, yet has no power. Best of all (that is, worst of all), it shifts the odds radically in favour of the “no” case. All they have to say is that it’s an ill-thought-out shemozzle. The “yes” case has to get an agreed-on version, and then sell it.

The response to this appears to be the Dad’s Army move: “Don’t tell him your name, Pike!” The plan appears to be to say that a) there’s enough detail out there and b) just vote on the general principle, anyway. Well, the detail is embedded in the 200-plus-page Langton-Calma report, which suggests a 24-person assembly chosen (not elected) by community sub-Voice assemblies, who are nevertheless different to existing community governance groups. Yet on the Garma Q&A on Monday night, Linda Burney very emphatically said of the final Voice form, “It’ll be elected.” The Langton-Calma report goes into great detail to say why the Voice shouldn’t be elected.

How did all this get to this? The Voice is being touted as something that more or less arose spontaneously from consultations around the many First Nations communities in the lead-up to the Uluru Statement from the Heart convention. But it is such a specifically designed proposal that one really doubts this. I don’t believe people are lying about this. Simply that the leadership running with it has been keen on the idea that Voice must precede Treaty, not strategically, but because there can be no legitimacy to Treaty without a Voice to, as Noel Pearson says, “treat between us the things we need to talk about” — or something.

The faith in the Voice seems to arise from the deep embeddedness of the leadership group in discourse, consultation and language, and draws on Anglo-American legal philosophy of right. In the conjuncture between leadership and consultation, a lot of people appear to have taken on a very similar way of talking, about a very specific sort of political object. In the process, it acquires a mystical glint, which gestures to notions of the pre-political.

Thus Roy Ah-See, very much part of the leadership push, told RN Breakfast that “[Voice critics] Lidia Thorpe represents a Green Voice and Jacinta Price a Blue Voice, but the Voice will represent a Black Voice!” How wonderful that Black opinion will be unitary and undivided, innocent of the divisions of actual politics — and presumably, of elected Black politicians, who, by this definition, are not Black at all. (Mr Ah-See’s services are available for life coaching.)

An alternative take on First Nations-settler relations, from the emphasis on Voice, is that the two sides don’t need to be constituted by discourse, that is itself to be constituted by a process from within the settler constitution. It would have been to say that the two parties ready for a treaty have been constituted by History in a process that no one seriously doubts anymore.

On that basis, a minimal treaty-statement — not a recognition; a core treaty, if you like — would become the act the referendum would have been based around. The “core treaty” then becomes the whole of the campaign. The “yes” side would then have had a proposition as simple and disseminable as the “no” side’s would have been. In the stoush we’re about to have, the “no” side’s volunteers will have a 3×5 card saying “the Voice is a third chamber”. The “yes” side will have a manual in a ring binder.

Jaysus, even a “core treaty” is tough. The daffy 1999 recognition went down six states to zero, 60%-plus against. And it had John Howard’s backing. But a “core treaty”, symbolic as it would be, would have laid the ground for treaty/agreements with material force — for an urban land reparations fund, for example. That in turn would have given the “core treaty” a retroactive materiality it had initially lacked. In that back-and-forth process, the basis of a changed relationship based on mutual recognition would have been born. In the political casino of the referendum, the House holds the advantage. You go in with the simplest plan to win, or you leave without your gold teeth. A simple treaty would have been the high card.

Well, maybe the opposition will come on board, and it’ll get up by acclaim. But as the referendum will be twinned with the election, they’ll surely wait and see what opposing it might be able to do for them. What’s happening now is that the referendum process is working as it was supposed to do, exposing a proposal to the scrutiny not of dozens or hundreds, but of thousands, then millions. The process will demand coherent detail or it will make visible the lack of such very smartly. Whatever happens, we are all part of it now, and the thing is in play.

Is the devil in the referendum detail? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

An interesting dry-run for the republic referendum. Will either kead to real change?

Or even “lead”

Dunno about ‘dry-run’ – the republic referendum was drowned at birth like an unwanted kitten.

I do think it needs more detail. Whether it has detail or not, its opponents will pick at it. So why not add detail to win those voters over who are approaching the concept with a positive frame of mind?

Australians generally do not understand the purpose of the constitution and it’s relationship to the workings of parliament. Without this people are expecting the constitution to include all the details which it cannot do. The Republican referendum had the same problem. Why didn’t they learn from that? Constitution states the principles. Parliament enacts the legislation to implement the principles. Noone knows how the legislation will turn out because of amendments, failure to pass bills and intervening elections etc. It is too late for people to understand this when media reinforce false beliefs that the legislation is already set in stone.

If anything is to get up out of this it needs to be right. Once it’s in the Constitution it’s there ‘forever’ be it good, bad or inconsequential. Also, actually having read the Uluṟu statement, I don’t believe Albo’s proposal is going to deliver anywhere near what the the First Nations mob envisaged.

Not sure how you can say that, as the ‘First Nations mob’ was so very vague about what they envisaged, and Albo’s proposal so far isn’t telling us anything more, or different.

Having said that we can read between the lines and note the fact that the Uluru Statement came out of a process where certain changes had been proposed to provide ‘constitutional recognition’. These were rejected as too symbolic and not substantive enough, so it’s fair to assume that the intention (even if only implicit) was something substantive, ie real power. So anybody who promises that it won’t be a ‘third chamber’ etc is contradicting that intention

They get around things in the constitution. I read the other day in the constitution that there should be no more than 7 ministers in the parliament but in 1952 via legislation it was changed to 30 and I think in recent years there were 34. (I may be wrong in some of that but I am pretty sure).

The constitution says that the monarch can annul any law within one year of it passing – not going to happen but still in the constitution! (number 59). Sometimes we can’t see the forest for the trees. Sky et al are trying to undermine trust in government.

GR, you are standing in front of a charging rhino with your hand held up to tell it to stop and give you some details. People are sick to death of political minutiae holding everything up, from fibre to the node (“duh”) to saving the planet (“Shouldn’t we just do it?”). There’s a logical progression involved – Uluru, respect, Voice, respect, Treaty, respect, No More Gap. The respect thing works like this: we respect them; they respect us; they respect themselves; then we can finally RESPECT OURSELVES!

Would ‘minutiae’ be meant to obscure the other, more common, word for ‘detail’?

As in “cui bono” because, sure as eggs is little bits of chook fruit, someone is going to do well and a lot of others … not so much.

The logical progression you describe is actually a chain of factual cause and effect, which remains to be seen. There is a serious debate to be had about whether political and constitutional changes alone can get rid of the gap, and if so which ones. It’s not just a matter of logic

Agree entirely and so clearly expressed.

“Well, the detail is embedded in the 200-plus-page Langton-Calma report, which suggests a 24-person assembly chosen (not elected) by community sub-Voice assemblies”

Really?

My reading is that they propose two models, one of which envisages uniform elections for the assembly, the other which gives some flexibility to regions to decide on the model of selection.

“This membership model provides flexibility and opportunity for the involvement of jurisdiction-level Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representative assemblies, where they exist, and elections if the Local & Regional Voices and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people of the relevant jurisdiction agree. ”

p.12. Optional elections at local level. But every local group could decide to choose reps collectively

So?

They’re not “suggest[ing] a 24-person assembly chosen (not elected) by community sub-Voice assemblies”, they’re saying it’s open to communities selecting members by methods other than a vote. They’re also saying they could choose to have a vote.

Choosing a rep. Would be difficult. A vote can be manipulated and so can consensus choice. Any ideas on how to select a representative ethically?