‘Legalised bribery’: Australia’s dirtiest corporations donate millions to Labor, Coalition and Palmer’s party, data reveals

Clive Palmer’s company Mineralogy blew political donation records when it reported more than $110m given to the UAP before the 2022 election.

Fossil fuel titans like Santos, Hancock Prospecting, Adani and Mineralogy are among the corporations that donated millions to the Australian Labor Party, the Coalition and the United Australia Party (UAP) last financial year, intensifying calls from powerbroker Greens to tighten the weakest donation and disclosure laws in the country.

This morning the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) released a tranche of data revealing exactly how much political parties and third parties spent leading up to the 2022 federal election, as well as the donations used to fund campaigns last financial year.

Among the heavy hitters are UAP founder Clive Palmer’s Queensland-based mining company, Mineralogy, which donated a staggering $116 million to the UAP ahead of the 2022 election, including two individual donations of $50 million and $30 million.

That means the UAP’s receipts total the highest yearly figure of any political party, smashing the party’s highly controversial 2019 total of $83.7 million.

Labor’s total donations were $124 million, with hefty chunks of money categorised under “other receipts” from the Minerals Council ($102,500) and energy giant Santos ($69,500).

The Liberals posted $106.7 million in donations and other receipts, and the Nationals reported $11.5 million, with donors including Adani Mining which gave $107,700 to the Queensland LNP, Gina Rinehart’s Hancock Prospecting which gave $24,500 to the Liberals, and Whitehaven Coal which donated $34,250 to the Liberal and National campaigns.

A slew of fossil fuel companies hedged their bets by spreading their donations across Labor, Liberal and the Nationals — including Beetaloo Basin gas fracking company Tamboran Resources ($200,000), gas producer Origin Energy ($11,480), Chevron ($93,090), Woodside ($109,930), and owner of Vales Point coal-fired power station Trevor St Baker ($120,249, including to the Liberal Democrats).

Overall the political duopoly got more than $2.3 million from fossil fuel sources ($1.4 million to Labor and more than $900,000 to the Coalition) — but $105 million declared by the major political parties had no identifiable source, up from $62 million in the previous year.

Still, that’s not the full picture. Acting legal director at the Human Rights Law Centre Alice Drury said many more millions in financial contributions to major parties were “obscured from public view entirely” because federal disclosure laws were riddled with holes.

“This situation is all perfectly legal under federal electoral laws, which are the weakest in the country,” Drury said. “We need greater transparency, of course, but that alone won’t change our politics. We also need caps on election spending and bans on large political donations altogether, as some states have done.”

Drury said the new data was a reminder that “big harmful industries are lurking in the halls of Australian Parliament, donating big and calling the shots”.

“This includes industries like tobacco, gambling and fossil fuels, which harm millions of Australians every year,” she said. “All parliamentarians who are serious about political integrity should support these reforms.”

It comes as the Greens — who hold a powerful 12 seats in the Senate — have intensified their campaign to cap federal political party donations to $1000 and ban fossil fuel companies from donating.

Greens Senator Larissa Waters said corporate donations were little more than “democracy for sale”, citing more than $230 million given to Labor and the Coalition in the past decade.

“With the Greens in the balance of power in the Senate, we have the opportunity to remove the influence of big money from politics once and for all,” Waters said. “Coal, gas and oil corporations don’t donate millions every year to the Liberals, Nationals and Labor because they’re huge fans of democracy — they do it because it gets results. Let’s call this what it is: legalised bribery.

“The influence of dirty donations on government decisions is why Australia has waited so long for stronger environmental protections and real action on climate change”.

The Greens are also calling for a rethink on donation disclosure. It should happen in real time, they said, with lower disclosure thresholds and better data.

Under the current system, voters have to wait up to 18 months before they can see donations to political parties.

It seems Labor is willing to listen. In a submission to a parliamentary inquiry into the 2022 election, Labor backed real-time disclosure and slashing the disclosure threshold from $15,200 to $1000 (though for 2021-22, the limit was $14,500 before indexation).

It would bring federal politics into line with state politics. In NSW and Queensland, the disclosure threshold is $1000, and in Victoria it’s $1080. In Queensland, Victoria and NSW, large donations to political parties (more than $6000) are prohibited.

Analysis from the Centre for Public Integrity, a non-profit group of former judges and anti-corruption campaigners, found the top 5% of donors made up three-quarters of nearly $1 billion in donations over the past 20 years. The top four spots were taken by Mineralogy Pty Ltd ($110,331,859), the Cormack Foundation ($63,644,555), Labor Holdings Pty Ltd ($62,360,236) and John Curtin House ($49,941,895).

In 2021, its research revealed that almost $1.5 billion in secret contributions had flowed to federal political parties since 1999.

The AEC's annual data dump on political donations gives voters a lot of information, but there's also a lot it doesn't tell voters.

It’s ostensibly a nod to political transparency and probity in federal politics, but experts in governance and law have long said serious shortcomings attend the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) data published annually under federal donations laws.

“Every year, there are large pools of money, the origin of which is not identified,” said Bill Browne, the director of democracy and accountability with the Australia Institute.

“It could be perfectly innocuous — many small donors, for instance — but the lack of transparency means we can’t answer questions about whether there is some deeper problem going on with these funds.”

More than $3 billion in income has flowed to political parties over the past two decades, with the origins of more than one-third of that sum obscured or cloaked in secrecy.

Last year alone, nearly 40% of party income, or $68 million, was of unexplained origin.

According to the Centre for Public Integrity, it’s a circumstance enabled by a series of weaknesses and loopholes in disclosure laws passed with bipartisan support.

Among the most obvious of these is the high disclosure threshold for political donations, currently set at $14,500, allowing donors to conceivably make multiple undisclosed donations under that threshold.

This same high threshold also applies to a larger, broad-sweeping category of income called “other receipts”, described by Browne as “really problematic” due to its tendency to disguise the ultimate source of the cash.

The category, he said, can include anything from returns on investment from so-called “associated entities” as well as public funding, loans received, payments for services and dividends on shares.

“The thresholds for disclosing donations and income are too high,” he said. “It means Australians never get a full picture of the money that’s funding our political parties and candidates and how influence is operating.”

Other gaps flagged include the narrow definition assigned to “gifts” or “donations” under disclosure laws, which do not extend, for example, to donations made at party fundraisers, commonly priced at up to $20,000 per person.

Rightly or wrongly, these factors fuel arguments around state capture and the perception that the game of politics is weighted against the public interest.

On Wednesday, the AEC published data revealing that the Liberal-National parties had disclosed more than $116 million in funding for the 2021-22 financial year, Labor $124 million, and the Greens more than $10 million.

Analysis undertaken by the Centre for Public Integrity suggests just a small handful of donors comprise around three-quarters of all donations.

“Given the reliance that the major parties have on these top donors, there is a real risk that they receive special access and yield undue influence on our decision-makers,” former NSW Court of Appeal judge Anthony Whealy KC told The Age.

“We urgently need a cap on political donations so that an average voter can match the donations of millionaires.”

But Browne said care would need to be exercised on this front, lest any reform inadvertently entrench the dominance of the two major parties to the detriment of independents or minor parties.

“Political donations caps are worthy, but they would need to be carefully designed to avoid unfairly disadvantaging challengers or independent candidates as opposed to incumbents,” he said.

“What the annual AEC data dump really reminds us is that we get information on political contributions very late, often months and months after the contribution has been made.

“If we had real-time disclosure [laws], voters would be able to weigh up the merits of these contributions at the time they occur and how they might influence political parties and politicians.”

The federal government has indicated it will likely reduce the disclosure threshold for donations and contributions to $1000, bringing it in line with thresholds set in many states across Australia.

And while it is also considering the merits of real-time disclosures, bans on large political donations appear to have been ruled out for the foreseeable future.

The media strategy saw Alan Tudge's media adviser plant stories with sympathetic 'right-wing' outlets and release personal details of victims.

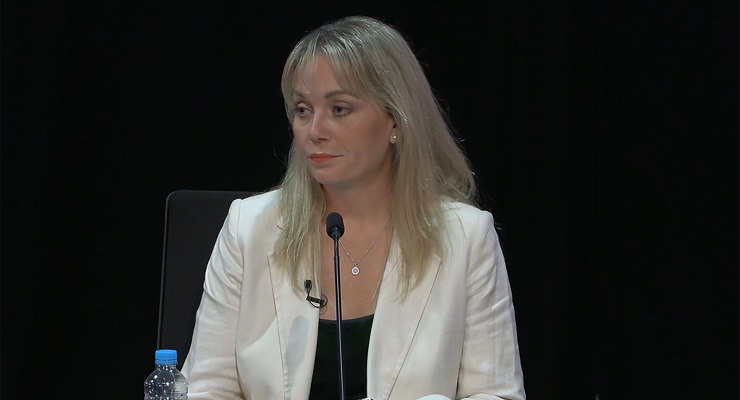

Alan Tudge’s former media adviser Rachelle Miller told the robodebt royal commission on Tuesday that she placed stories with “friendly”, “right-wing” media outlets to counter critical media coverage of the scheme, before releasing victims’ personal details.

Miller told the commission in a statement that by early 2017, negative coverage of the robodebt scandal had cascaded into a “media crisis”, which Tudge gave “firm” instructions to “shut down”.

The royal commission, which was established in August, is investigating how the illegal scheme was established in 2015 and allowed to run until November 2019, before ending with a $1.8 billion settlement with nearly 400,000 known victims.

Under questioning, Miller said she devised a media strategy to counter the negative coverage in “left-wing” media that involved placing stories with more sympathetic outlets across the News Corp stable about how the Coalition was “catching people who were cheating the welfare system”.

“The media strategy we developed was to run a counter-narrative in the more friendly media such as The Australian and the tabloids, which we knew were interested in running stories about welfare system integrity and the supposed ‘dole-bludgers’,” she wrote in her statement.

Miller said the office wasn’t particularly worried about the negative coverage in late 2016, which at the time was being led by Guardian Australia, because “it wasn’t unusual” for the left-leaning press to be “attacking us over social policy”.

Once the issue began to attract coverage in other outlets, she said, then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull became “unhappy”. Tudge as a result became adamant the government should defend itself and be “correcting the record”.

Tudge sent his former chief of staff an article written by Peter Martin in The Sydney Morning Herald in an email, saying “PM sent me this one and has the clearest critique”, the commission was shown.

Martin had written: “The humans charged with applying the law didn’t issue debt notices unless they had evidence debts existed. To do so without evidence would be to break the law.”

Miller told the commission that Turnbull liked reading The Sydney Morning Herald. When asked where the Herald fit into her spectrum of partisan media coverage, Miller told commissioner Catherine Holmes AC SC it fit into the “left-wing” media camp.

“Left wing!” Holmes responded.

The bolstered media offensive then saw the minister’s office and the department actively seek to disprove claims made by victims of the scheme in the media.

Miller said Tudge requested the files of “every single person” who appeared in news reports on the scheme so “we could understand the details of their case”.

The bolstered media strategy included “correcting the record” in instances where victims had gone to media with their stories and made claims the department and the minister’s office deemed incorrect.

She was asked about the process that led to the release of victims’ personal details. The commission heard that Miller discussed the partial release of information against the recipient with Bevan Hannan, her media counterpart at the department, and chief counsel Annette Musolino, who cleared the release, which only drew more criticism.

One example of the office using right-wing media to combat criticism was a story written on January 26 2017 by Simon Benson in The Australian, headlined: “Centrelink debt scare backfires on Labor”.

The story said the department “confirmed” that a number of victims who said they were wrongly targeted had “in fact” accepted that the debt averaged by the scheme was owed.

“That was an article we liked,” Miller said.

Tudge has repeatedly rejected and denied Miller’s claims, and is scheduled to appear before the royal commission today, before former attorney-general Christian Porter is scheduled to appear tomorrow.

Miller alleged in 2021 that Tudge was abusive towards her during a consensual affair, and later accepted a $650,000 settlement from the federal government after claiming she suffered hurt, distress and humiliation during her time working for both Tudge and Michaelia Cash.

The dead cardinal has left the Catholic Church in Australia in terrible shape, and there are no signs it has any chance of getting well again.

As the late cardinal George Pell is moved to his final resting place in the crypt of Sydney’s St Mary’s Cathedral tomorrow, his supporters will mourn the passing of a saint gone too soon. It is perhaps trite to observe that there are many who say his departure couldn’t have come soon enough — but that would hardly be in the spirit of the occasion.

Pell’s opponents — some, anyway — will be outside, perhaps cordoned off and held at bay by the force of NSW Police, as they rally to give voice to the anguish of those abused by the clergy. The reckoning will show, however, that for all his adherence to black-letter scripture, Australia’s most prominent Catholic has left the church in terrible shape.

Church attendances have plummeted from historic highs. And never has the church’s influence on public policy been so weak. Proof of its diminished role in the spiritual and earthly life of Australia comes via a study conducted by the church itself.

The National Centre for Pastoral Research is part of the Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, a national secretariat for the most senior clergy. Its data is drawn from churches across the country and married with national census data. The most recent analysis was published at the end of 2020 and reflects the numbers as they were in 2016. The study provides a 20-year comparison, stretching back to 1996 — a helpful time span because it neatly coincides with the period of the church’s almighty fall from its peak of power.

The study found that in 2016, the number of people attending Mass on a typical weekend was about 623,400, or 11.8% of the general Catholic population. In 1996 it was 864,000, about 18% of the Catholic population.

The most dramatic fall came in the number of Australian-born attendees and those born in English-speaking countries; numbers almost halved in the 20 years. At the same time the percentage of attendees born in non-English-speaking countries had risen from about 18% to almost 37% in 2016, an increase of about 72,600.

Those attending Mass were much older than the general Catholic population — a third were aged between 60 and 74, and the trend shows attendees are only getting older.

There was another striking contrast between the Catholic population overall and the Mass-attending population. Just over three in every five attendees were women, a ratio which had been constant for decades. The study reported “a lack of youth and young adults of both sexes”.

The study concluded that the impact of the findings from the Royal Commission into Institutional Reponses to Child Sexual Abuse had been “particularly significant”. A secondary finding was that young adult attendees were not being replaced by younger people as they age. This showed “how much the church in Australia owed to our immigrants, particularly those from non-English-speaking countries”.

Rise and fall as a political influence

In 1996, Pell’s influence was decidedly on the rise. He was appointed archbishop of Melbourne, having served as a parish priest and bishop for the southern region of Melbourne. His elevation to genuine church power coincided with the election of the Howard government.

He was invited as a delegate to the Australian Constitutional Convention in 1998 to consider the issue of the republic. In 2003 he received the Centenary Medal from the Australian government. Two years later he was made a Companion of the Order of Australia (AC), the highest of Australia’s honours. In the meantime, the Victorian-born Pell had been appointed archbishop of Sydney.

From his mighty heights Pell engineered the succession of like-minded conservative Catholics, fashioning the church in his own image. In Canberra his chief backer, Tony Abbott, was elected prime minister in 2013. If this was the high watermark of Pell’s influence it was set to change.

The royal commission was by now an unstoppable force, adding to the steady stream of revelations of church sex abuse which had emerged in prior years. The church’s moral authority was shot and with it its ability to halt political reform in the areas of life, death and marriage which the church had always claimed as its own.

If any period captured the church’s fall it was 2017. The losses were many. It was the year that Pell was charged by Victoria Police with historic child sex offences (ultimately dismissed by the High Court). It was the year same-sex marriage legislation was passed in the federal Parliament. To cap it off, in November of that year, Victoria became the first state to pass voluntary assisted dying (VAD) legislation, in the face of the church’s intense public opposition. The Andrews’ government legislation opened the way for state parliaments to pass similar laws. Even NSW, the home of the powerful Sydney archdiocese, surrendered to the public will.

Last year federal Parliament passed laws to return the power to territories to enact VAD laws. Symbolically it was a full turning of the wheel. In 1997 senior Catholic figures in and around the federal Parliament (including then lobbyist and now Albanese minister Tony Burke) had worked to pass the laws which removed those rights from the territories.

By 2022 the church’s ability to stop change by threatening political reprisals was no more. It had become a paper tiger.

Raging against the dying of the might

Yet the fall is not universally recognised. There are corners of Pell’s once mighty empire where the world appears to have stopped 20 years ago, when the church held sway in the public square and where there was still a respectable attendance at Sunday Mass.

One of those holdouts is, naturally, the Sydney archdiocese, under Pell acolyte Archbishop Anthony “Boy George” Fisher. The archdiocese has become increasingly strident about Catholic politicians who don’t do their religious duty in the Parliament. The Catholic Weekly said NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet’s decision to allow a conscience vote on VAD was “one of the most humiliating examples of meek acceptance of evil ever seen”.

Andrews, Victoria’s Catholic premier, is regularly lambasted by the Murdoch media for failing to behave as a Catholic should. His sins are many but top of the list must be that he allowed VAD legislation to proceed and he consistently showed Pell approximately zero respect.

The trouble for the church is that outside of a very small bubble no one else is listening.

Tomorrow, by coincidence, a coalition of 20 Catholic groups under the banner of the Australasian Catholic Coalition for Church Reform will gather to press for a different and more inclusive church.

The symbolism couldn’t be sharper.

The ClubsNSW CEO has been sacked for comments he made about NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet. But Landis has a history of verbal stoushing.

ClubsNSW CEO Josh Landis was sacked yesterday for suggesting Dominic Perrottet’s drive for cashless gaming cards was being driven by his “Catholic gut”.

The NSW premier didn’t miss when he appeared on Ben Fordham’s 2GB Breakfast show yesterday, calling the comments “inappropriate and offensive”.

By lunchtime, Landis had quickly capitulated, offering an unreserved public apology but by 4pm the ClubsNSW board had met and his sacking was announced.

When it comes to industry lobbyists, Landis is one of the most aggressive. This perhaps reflects his background as a lawyer and a staffer in the NSW Labor Right, and the training on political influencing he famously did in 2013 at the US National Rifle Association after helping tear down the Gillard-Wilkie mandatory pre-commitment reforms.

Five years ago, I was doing communications for The Alliance for Gambling Reform and Landis held the equivalent position at ClubsNSW, so I sent him this relatively innocuous email:

From: Stephen Mayne

Sent: Monday, 26 March 2018 6:35 PM

To: Josh Landis

Subject: quick query

Hi Josh,

I’m just doing some research on the bigger clubs in ClubsNSW.

Are you aware of any that have multiple venues without poker machines?

Kind regards

Stephen Mayne

On arriving at the ClubsNSW office the next morning, the former adviser to controversial NSW Labor treasurer Eric Roozendaal wasted little time starting some unpleasantries, as follows:

From: Josh Landis

Sent: Tuesday, 27 March 2018 8:58 AM

To: Stephen Mayne

Subject: RE: quick query

Dear Stephen

Thank you for your email. I’d be delighted to help you, as you will be to help us.

To that end, can you advise who has donated to the Alliance for Gambling Reform and how much money they donated in the last two financial years? How much did the estate of Mr Paul Bendat contribute? I’d like to know whether Alliance donors are offered a tax deduction for their donation.

Is Tim Costello a paid spokesman for the Alliance? If so, how much?

Recognising that, on behalf of the Alliance, Tim Costello declared the Tasmanian election “a referendum on gambling in Australia”, and the result was confirmed in South Australia, when will the Alliance cease operating and how many cents in the dollar can donors expect to be refunded on liquidation?

Josh Landis

Executive Manager – Public Affairs

ClubsNSW / ClubsAustralia

Within three hours, I politely returned serve at 11.52am on March 27 with the following email:

Hi Josh,

Paul Bendat wasn’t really involved with The Alliance and certainly nothing has flowed to The Alliance from his estate. The majority of our funding comes from Victorian local government so the tax deductibility is not relevant.

Tim Costello is a volunteer, so unpaid. I signed up with The Alliance in May 2016 as a part timer and thus far have received less than $50,000 in gross pay.

How much are you on?

Cheers, Stephen Mayne

Once again, Josh was quick out of the blocks and replied as follows at 12.38pm, finally dealing with the substantive inquiry but then ending with more gratuitous insults:

Stephen,

Thanks for your reply.

You should be aware that very few clubs in NSW are without gaming (approx 150 of 1300). I have several examples off the top of my head which are in club groups:

Camperdown Commons is a club without gaming machines. It sits on the old Camperdown Bowling Club site (which previously had gaming) and was extensively redeveloped following amalgamation with Canterbury-Hurlstone Park RSL, which is a fairly big gaming club.

West’s Bowling Club is a gaming-free venue in Newcastle that is part of the Wests Newcastle Group. Club Italia is part of the Mounties Group and it has no gaming machines. Belfield RSL is part of Canterbury Leagues Club Group and has no gaming.

We’re a not-for-profit industry and the salaries of our people reflect that.

How much has the Alliance spent campaigning for change in Tasmania, South Australia and NSW? Has the Alliance formally notified its Victorian Local Govt funders how much of the annual budget was spent outside of Victoria?

Seeing as Mr Costello has a tendency to make hyperbolic and factually inaccurate statements, when will you be replacing him as the main spokesperson?

Josh

Five years later and Tim Costello is still doing a great job fighting the pokies, and the window of opportunity has suddenly opened right up in the ClubsNSW heartland. Its national subsidiary Clubs Australia is used to completely owning NSW politics and sending its fixers off to put out fires in other states, but it feels different this time.

Landis was promoted from the pokie club spin doctor role to the top job when the long-serving ClubsNSW CEO Anthony Ball resigned in 2020 to head up government and stakeholder relations at pokies giant Aristocrat Leisure.

Ball can also be quite threatening and insulting in his communications. When former senator and long-time gambling reform advocate Nick Xenophon fell short in his bid to become a big player in the South Australian Parliament, Ball sent him an unsolicited text at 11.55pm on 17 March 2018 which simply said:

“Sorry Nick. We will kill you all off.”

I raised this conduct with the Aristocrat board during the recent interview process for the coming contested board election at the February 24 AGM and suggested it dissociates from Ball. So far, it is standing by its man, but using the word “kill” in communications with a senior politician is not something which would be tolerated at many companies.

In the end, these ClubsNSW directors showed some spine sacking Landis yesterday and if these Aristocrat directors were managing their reputational risks, they would be putting as much distance between their $22 billion company and NRA-trained ClubsNSW heavies as possible.

It truly is remarkable that NSW has 90,000 pokies spread across 2600 pubs and clubs, which annually drain about $7 billion a year from the community. They also aid and abet widespread criminal money laundering through the washing of dirty cash into Aristocrat machines which can still accept up to $10,000 through their note acceptors in a single session before you need to actually place a bet.

Eliminating cash entirely might reduce annual pokies losses to perhaps $6 billion, but if you believe journalists such as The Daily Telegraph’s rugby league writer Phil Rothfield, such a move “could have a devastating effect” on clubs such as Canterbury-Bankstown.

Most NRL clubs are independently profitable without relying on their associated suburban casinos, but an unnamed Canterbury-Bankstown director told Rothfield the anti-money laundering card “could cripple us”.

Last year the Canterbury League Club made an $11 million profit and gave the NRL club $5.8 million. Rothfield confidently asserted: “That money won’t be there in future years with these new gaming cards.”

As Michael Pascoe also detailed in this excellent piece in The New Daily unpicking ClubsNSW use of country newspapers to criticise unfriendly politicians, it is surprising how many media outlets still fall for ClubsNSW’s hollow talking points.

Now that Landis is gone, the ClubsNSW board has an opportunity to completely overhaul its approach, starting by pulling this old school website which urges citizens to email their local NSW state MP to campaign against an anti-money laundering card.

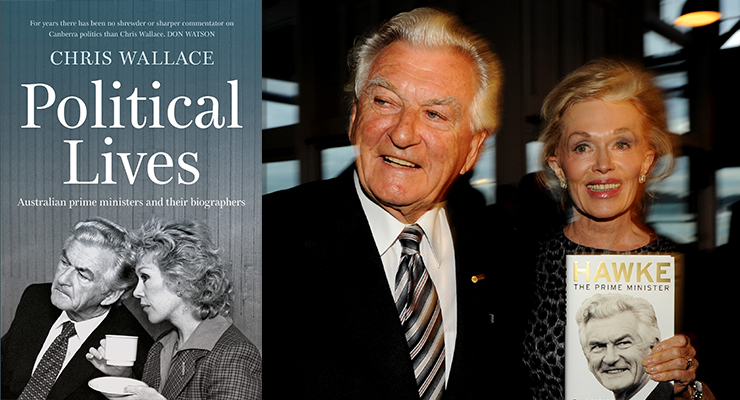

A new book examines the biographers of prime ministers past, raising a critical eye to those varied chroniclers of Australia's political history.

In Political Lives: Australian prime ministers and their biographers, Chris Wallace has given us something to be nostalgic about. Not the prime ministers — they’re as flawed as they’ve always been. Rather, it’s the journalists of yesteryear who seem better equipped to tackle those politicians and make meaningful stories out of them.

Wallace, a political historian, is at heart an irrepressible journalist. Naturally Political Lives is a romping read (there is, after all, an intimate 32-page account of former prime minister Bob Hawke, his wife Blanche d’Alpuget and their biographical exertions). There’s plenty of stuff for political junkies too: lively portraits of Australia’s first 25 prime ministers; gripping accounts of their contemporaneous chroniclers.

And there’s a serious argument here. “Reputation is political capital,” Wallace writes. “Biographers are among those who coin it, and who can destroy it, as well as providing the material for others to do the same for their own multifarious reasons.”

In other words, life stories matter in the public sphere, and those who fashion them must take the craft seriously. Wallace takes it more seriously than most: she decided not to publish her nearly completed biography of Julia Gillard during the latter’s turbulent prime ministership. She didn’t want to be a propagandist for Gillard, or for her opponents.

This time, she deals with material that cannot feed the political sharks. In fact, journalists, rather than politicians, are the most vivid characters.

There’s much admiration for those who preceded Wallace in chancing their arm at political biography, particularly those who did so from the vantage point of the Canberra press gallery. The work of the journalist-biographer is something Wallace largely celebrates, whether it’s the “insightful” Arthur Buchanan writing about the lives of early federal leaders, only to die with those sketches unpublished; the “experienced” and much-maligned Allan Dawes carefully excavating the skeletons in Menzies’ political closet until he is sent packing; or the “pioneering” financial columnist Edna Carew coaxing testimony from a Paul Keating who was at that time hungrier to lead than to read.

These qualities are emulated in Wallace’s approach to historical inquiry. The reader sees her sleuthing through the National Library’s manuscripts, assiduously contacting the living subjects of her story, and “making do” with occasionally limited material to get to the “biographical angle” of political culture.

She’s not completely uncritical of her forebears though, and for good reason. Political biographies were mostly written by “white male journalists”; regrettable, because it reproduces a kind of political “monoculture”. Journalists are easily tempted to become a “participant” rather than a observer, and they’re sometimes pressured into “concealing” that which they cannot place on the record.

Most damningly, they have been far too “shy of the psychological”, the result being that the public knows “just that much less about their potential and serving prime ministers”.

But what exactly do voters want to know? Years of sleaze and scandal have left Australians a little exasperated with their politicians’ private lives, and wary of the way journalists engage with them. There have been just too many revelations of ministerial affairs with staffers, conducted in lavish motels and then hushed up with cash settlements, all funded by the taxpayer.

Having paid for it all, voters might reasonably have expected a bit more rigour from their reporters, except that they have also sometimes been in bed with the politicians — literally, as well as figuratively. Instead, the mystique of the modern political report seems calibrated to disguise either collusion or carelessness.

The 2022 federal election campaign is a case in point. Much media coverage was biographically myopic, historically illiterate, and allergic to anything resembling political insight. There were sharp biographic profiles to be sketched and political psychologies to be gleaned. But then again, such an exercise required questions other than: “What’s the cash rate, Mr Albanese?”

In any event, prospective leaders still try their best to give the people mini-biographies along the way. Albanese has been good at managing his life narrative for political effect.

Samantha Maiden wrote in Party Animals (2020) that the prime minister had spent many years telling anyone who would listen that he didn’t have a “destiny thing” like Hawke. By May 2022, voters had heard repeatedly about the Marrickville boy from public housing and his single (often seriously unwell) mother.

If they hadn’t read Karen Middleton’s 2016 biography of Albanese, Telling It Straight, they could hear the plot summary on 60 Minutes — if the previous week’s footage of Scott Morrison butchering “April Sun in Cuba” on his ukelele hadn’t turned them off the program for good.

It’s not that political lives matter more or less today than in the time of Whitlam and Fraser or Hawke and Keating. Albanese’s story, for instance, clearly meant something to many who voted for him. There was much respect for his life story, even if there was equal enthusiasm in some quarters to hear a bit more about policy.

There will be plenty more biographies of plenty more (aspiring) prime ministers. And there will be more biographers to interrogate and showcase those lives. Some will be journalists, but Wallace implores authors from diverse backgrounds to have a go at the craft in the hope of fostering a less stale political culture.

She’s wise to do so. The best of the books she studied, Blanche d’Alpuget’s Robert J Hawke, was written by someone who described herself as “not a good journalist”.

There is much to admire about the Albanese government's national culture policy, but Indigenous peoples need more than it offers.

Six months ago, when it was announced that the new Labor government would draft a national culture policy, your correspondent suggested it could be reduced to three points: having culture that the market won’t fund is good, so the government should fund it; granting of this funding should be shaped to maximise equality of access; large-scale broadcasters should be subject to local content quotas.

That was it. That was all you needed.

On looking at Revive, the new national cultural policy document (so called because titling it “Breathe, Damn You, Breathe” would have been unseemly), I wondered if Labor had taken up my suggestion. There is nothing of the grand pronouncements of past documents about what culture is or how it serves a nation.

There are a lot of stories about how important stories are, case studies (“Gruppo Whoop-Di-Do of Marble Bar WA is using mime, earthworks and the oboe to show a new side to Charmain Clift”, etc), oodles of recommendations and initiatives, and a lotta lotta First Nations stuff, but no big national cultural branding. Has cultural policy learnt its lesson?

Sadly, no. The First Nations stuff, as well as being good initiatives in their own right, is the national branding. First Nations First leads the “five pillars” of the policy (which support 10 principles, which the document does not call “the principles architrave” — philistines), and it’s made clear that this is the most important pillar, even though that’s not how pillars work. It’s the way to solve the problem of an Australian cultural identity when every other way of shaping it has been exhausted.

That process may honour and fund First Nations cultures, but it also co-opts and appropriates them, to a nation of which they are one part, and to which they have a complex and ambiguous relationship. I shall explain.

The Albanese government faced a problem when it went to create a national culture policy. It would have been desperate not to recycle, for one last time, some sort of left-critical cultural nationalism, the faintest echo of the Whitlam years. Not only would that have been an imposition of a de facto Anglo-Celtic obsession that has been rendered obsolescent by waves of immigration, but for many artists it marks a history so saturated with notions of colonialism that it cannot be owned by the government. Nor is there any desire to. At the same time, in 2023, it cannot actually have no thematic policy at all, a sort of Burkean (Edmund, not Tony) conservative refusal to have any programmatic policy at all.

This is not a dilemma that I am suggesting it is responding to cynically. It looks ahead, as left nationalist social democrat neoliberals, and sees a giant hole in the middle of a culture policy with all sorts of bells and whistles. It looks for what’s missing. Where once it would have found a national culture, it now finds a First Nations culture (or two mega-cultures, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) that must be our missing content. What else could it be?

This is the deep logic driving the policy. The last outing of left cultural nationalism was under the Rudd government, which steered funds towards work that would tell our history in a critical fashion. The result was that TV networks took the bucks and made hagiographies about their founders (Howzat! Kerry Packer’s War, Black and White), while Martin Ferguson blew tens of millions of taxpayers’ money on Baz Luhrmann’s crappalaooza Australia. After that Mr Tony knighted Prince Philip to try to restore our British continuity, Malcolm looked to the future, and Scotty beamed us up to Star Trek, reminding us that Captain Kirk was Captain Cook, and both were Jesus.

Anglo-Celtic culture dominates…

That time to be alive is over. The new one begins. For about 125, maybe 150 years, we had a reasonably defined culture in the fullest sense of the term: that of multiple practices of meaning from the immediate — how people bodily greet each other, the brands they buy — to the more deliberate processes of reading and writing, listening and playing, etc.

But the “we” was Anglo-Celtic Australia. With First Nations peoples sequestered or subjugated and all but a few foreigners excluded, we were possibly the most Anglo-Celtic nation on earth, outside Scotland and Ireland. Protectionism made us self-sufficient: we had our own architecture and our own biscuits, plays and short stories, and everything in between. A lot of British stuff came in, but a lot of what we lived by was home-grown. That persisted even as American products and styles began to flow into parts of the market.

When the first wave of social liberalism came with the boomers in the late ’60s and early ’70s, a reshaping of the culture was seen in those terms. The biscuits were all very nice, but we wanted our own movies too, as we would have had if the Lyons government (advised by a bloke named George Palmer; I wonder what happened to his little boy Clive?) had not killed the industry in the ’30s.

So a broad movement arose in every art form and genre to reclaim a national culture in the name of its independent and democratic spirit. The First Nations part of all this was expressed by the Black Power movement, which connected to global Blackness, rather than indigeneity. The statement “You are on Aboriginal land” was part of a wider socialist notion that we would get the land back for the whole population (and the land councils, with their pre-Mabo judgment notion of land returned by right, without the question of an abstract “title”, was an expression of that).

There was enough of this around after the 1975 coup for Malcolm Fraser to merely reduce the funding, rather than change the direction — though he nobbled the anthem changeover, a new flag and other stuff — and a cultural leftism was one of the features of the Hawke government. But so too was offering to let the US test its missiles in our waters.

This was the two-step that has become Labor’s modus operandi: give in the culture, take away in the economy and society. Every time Victoria’s Daniel Andrews government does something like offering a “non-binary” checklist option on dog licences or some such it uses the resulting cheers to cover the noise of privatising VicRoads.

By the late 1980s, we had Aussie films, but the biscuits — and the burgers, supermarkets, soft drinks, clothes and cars — were increasingly American or global. The films increasingly were crap. Once the political push for a left nationalism had died away, the culture carapace that remained began to wilt. In the early 1990s, the tariff walls came down, Australian brands disappeared, pay TV and diluted quotas drowned out Australian content.

Paul Keating’s version of the culture-politics two-step was disastrous, destroying much of what remained of an everyday cultural base through the final destruction of the tariff walls, while giving big cheques to individual artists.

… Anglo-Celtic dominance ended forever

John Howard? Well, as a conservative, he was a classic cunctator, seeing his role as holding the line against any wrenching progressive shift until the last World War II vet had died. His political wars — Tampa, the intervention — were gonzo mayhem, the culture wars more measured. Howard knew the great globalisation wrench was coming because he made it possible: high immigration ended Australian Anglo-Celtic dominance forever, as deregulation further Americanised everyday life.

Rudd’s tergiversations were an attempt to work with the new framework he had inherited and try to get a leftish, popular result. Part of this was the history stuff, and part of it was adopting the “progressive patriotism” of Tim Soutphommasane, which attempted to reflow cultural attachments to abstract principles we had lived by (allegedly), and which rather made things worse.

What we face as a nation now after a decade — was it a decade? — of reactionary malarky was to either accept that we were a nation with culture, but without a culture, or to find a wholly new way to brand it. And any new attempt to construct it afresh from “majority materials” would collapse in immediate absurdity.

In Revive, First Nations cultures have been subbed in as a new form of the Australian brand, facing inwards to the country and outwards to the world. Indeed, this cultural First Nations First process is used in the Revive report to lace politics and culture together, with the first principle of the First Nations report being to ratify the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Since several of the nation’s leading First Nations artists are from groups such as Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance, which has a dissident relationship to the Uluru Statement, this seems like co-option.

But of course it is. Without a full treaty and sovereignty process, the subbing in of First Nations cultures to serve as a metonym for a country that can’t have a culture is surely appropriation on a grand scale. This has been occurring for some time, driven by the white progressive classes and done under the cover of acknowledgment. White progressives have latched on to First Nations acknowledgment out of genuine ethical passion, but also out of cultural need. The frameworks of progressivist/knowledge class life are abstract, generalised. First Nations cultures retain rich and compressed meanings, which can assuage progressive anomie.

This is why the polarities of Australian left cultural nationalism have flipped so absolutely. The Anglo-centred left nationalism of the 1960s to 1980s now looks simultaneously kitsch and offensive. The Australian left nationalist view of that period was that the country’s history was evolutionary and dialectical: within a cruel and racist colony, a universal spirit had unfolded, asserting itself and extending from its particular beginnings into a general form. This is why left nationalists revisited events such as the Eureka Stockade, the eight-hour-day protests, universal suffrage, and the like. This movement not only reclaimed the Eureka flag, it turned Blinky Bill into a folk revolutionary.

Much of this now looks like National Trust, open-house day dress-ups. And, by that, worse, since it fails to acknowledge colonialism. The critical meaning of that has overwhelmed any notion that Australia’s history was an emergence of greater good out of evil beginnings — 95% of our history is now, among the broader, say, 30-40% who debate these things, an orphan.

Sticking to a rigid and servile history

Thus the right latch on to the most rigid and servile parts of our history — from the ludicrous overestimation of Robert Menzies to the ghastly death mall the Australian War Memorial is being turned into — with the living, progressive and responsive side of our history rendered as a null set. The right charges ahead unhindered. But there is practically no one remaining on the left who identifies emotionally with that progressive cultural-historical stream. The communists and Maoists did, but they are long gone. The Labor left once did. But it’s a farmer’s axe, changed over completely in a couple of decades, now near all deracinated progressives, and perhaps the main drivers of the appropriation of First Nations cultures.

There is thus an enormous weight being placed on First Nations cultures, with the Voice and the cultural policy simply the leading edge of a pretty major process. This process remains a progressive passion, with much of the population watching on, living the culture — of sport, of Australian music that doesn’t need a grant, of the ways in which one does culture in how you holiday, or have a barbecue or whatever — while watching the process of state culture-making with the certain knowledge that the mass of the population are more excluded from this process than they have ever been.

The response to that at the moment is simply withdrawal to the “private social sphere”, and a protective cynicism to make bearable the spectacle of one’s own powerlessness.

But it may not be so forever. The uses to which the national cultural policy is putting First Nations cultures — to give a positive branding to the nation that almost extinguished them — are part of the enormous weight being put on First Nations peoples to save Australia from an encroaching anomie, the “kingdom of nothingness” that lies beneath “the vernacular republic”.

I do not see how it can bear the weight of such expectations and demand indefinitely. It’s only February, and with the Voice and the cultural policy and more to come, we are really wearing out this new self-branding at a pretty rapid rate.

This should be obvious for what it is, whether done by progressives needing to import rich meaning into their own lives, or a national government (I doubt that the 14 culturati appointed to advise the process are complicit in this switcheroo) needing to give the country an identity on the world stage. Without material transfer — urban land, reparations, capital — it is extraction and exploitation.

We are mining First Nations cultures just as we have mined their lands, and giving them back fees in the form of expanded arts grants. We alibi this on the suggestion that a cultural-symbolic resource is iterative, i.e. the song, image, story I am co-opting is reproduced, not taken, as is land or iron ore.

But that is not hard and fast. The more we abstract particular cultural properties — including texts and performances — from more immediate contexts or relationships, from their existence as culture unbent to wider purpose, we wear down the rich meaning we go to them for, dilute it, in a way that feeds back into the social life from which such culture comes.

I cannot imagine First Nations peoples will consent en masse to this forever; nor that the excluded mass society will agree forever that a national culture is what progressives and artists re-engineer it to be.

Revive has many good things in it, some shockingly bad ones, and both for First Nations peoples, but it is above all a document of wider intent by the Albanese government, and forms a statement of intent as to what it will do in the fields of economy, trade, foreign policy, and above all defence. And that show is just about to start!

Does Revive use First Nations cultures to assuage our conscience? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Winning a fourth term in NSW could be a major step on the road to redemption for the Liberal Party — and may stop the teal wave.

The Liberal Party is in soul-searching mode, having lost elections in every jurisdiction other than New South Wales and Tasmania. But if NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet can win a fourth term in March, holding on to our most populated state, it will send a clear message of how the party can begin a redemption arc.

At the federal election, a majority of women preferred Labor in all age segments. So, yes, we have a women issue. Even this year our preselections haven’t been good enough, but that says more about some of our dysfunctional, self-interested and obstinate members than it does about our leaders.

What I hope the voters of NSW can see is the difference between what we took to the polls federally last year, and what we’re taking to this year’s state election. The branding between former prime minister Scott Morrison and Perrottet is very different. The big question, however, will be whether the trends we saw at the federal election will be replicated — I’m talking about the teal elephant in the room.

I’ve been asked a lot during the past year as to why I, a young professional woman in my 30s, won’t be voting for the teals in March. The answer is that I strongly believe that everything last year’s teals were advocating for are the very things the Perrottet government has a proven track record delivering.

I also would prefer to back a political party than an independent; the teals can never hold a portfolio and never form a government. As we’ve seen federally, other than David Pocock, the teals will struggle to have much power at all this term.

Last year the teals took a slogan of climate, integrity and gender to the election. They marketed themselves as the good type of political leadership, bold and courageous with good morals, rather than greedy, corrupt and untrustworthy. Essentially the political version of ESG in finance. It was a clever political strategy — and it worked.

The problem shared by today’s politicians is that we all have the attention span of gnats. Unless you can present a complex, considered policy in digestible, bite-sized pieces — or in 280 characters — you’re doomed. It leaves voters worse off, too; we become oblivious to the nuance and intricacies of the policies we think we’re voting for.

The teals were light, if not non-existent, on policy, stuck in no-woman’s-land, boasting of their independence while sharing colours and money just like a political party. They said they wanted climate action, yet their policy on emissions cuts varied vastly. But who cared? Voters read the word “climate” and that’s all that mattered.

When it comes to policy, I find it patronising when we talk about “female policy”. Like we want a free ironing board or a vacuum cleaner for our votes. We pussycats value similar things to our male counterparts. However, we can’t ignore statistics.

In a 2018 report, it found women aged 18-33 are eight times more likely than men to believe processes of climate change will affect their lives. We also know the Liberals’ two-party-preferred vote was the weakest among women aged 18-34.

As a woman in my 30s with an open affiliation to the Liberal Party and who has six years working at Sky News, it surprises no one that I’m not Twitter’s cup of tea. I’m pretty consistently told by big-brained men and condescending women that my party isn’t doing enough on climate — and that this is why they’ll be voting elsewhere this March.

Sure, fill your boots. But the inconvenient truth they’ll have to contend with is this: the NSW Liberal government is leading the way on climate. If you don’t believe me, a mere Liberal hack, a quick google of the World Wildlife Fund will show the Perrottet government as the top performer on renewables. By the way, in second place is the only other Liberal-governed state, Tasmania. Drats! Really throws that narrative out the window.

In NSW we also have an established integrity commission and the most female-focused policy agenda of any state in the country. The state has led the way in its groundbreaking early education plan. We passed affirmative consent and invested a record amount of funding in preventative measures and support for domestic violence. We increased options for parental leave and provided financial support for women going through IVF.

This isn’t flowery ironing board and vacuum cleaner crap. These are tangible policies that will help women.

I’m a Liberal because I believe in the ethos of the party. Free markets, competition, freedom of speech, personal accountability and small governments that don’t insert themselves into every area of your life.

Of course, those values only go so far. A good leader knows when it’s more important to be a premier than it is to be a Liberal, and that is what Perrottet has shown. The cashless gambling card actually goes against the grain of Liberal free-market values, but it is unquestionably the right decision for our state and in our citizens’ best interest — residents in NSW have lost $135 billion since the introduction of poker machines 30 years ago.

Regardless of political allegiance, if you have come to power in the past decade, one of your biggest responsibilities should be diluting culture wars that only further polarise a fractured society. Perrottet has done well to avoid fanning the flames for political gains.

Also, despite being religious, he doesn’t rule as a Christian. The Berejiklian and Perrottet governments allowed bills to go to a conscience vote on things like abortion and euthanasia. To me, as a non-Christian, that is important.

When it comes to fixing our women issue, the mistake the Liberal Party continues to make is that we’re trying to pretend it’s a clandestine problem no one knows about. (Guys, I think they know.)

We need to change tack and start being explicit about why we are the way we are. When we explain it, it actually makes perfect sense: we’re hamstrung to our membership. Members wield a lot of power in the preselection process, and our average member is a male in his 60s. Until we see a rapid influx of women and a rapid decrease in the average age of our membership, it will be difficult to change.

This is why I am trying to flood the party with women aged 30-60 by launching Hilma’s Network. I mean, other than begging, how do we attract these exotic creatures?! By trying, for starters. By holding curated events that appeal to them. It’s about showing women that we know we haven’t been good enough for them and that we are trying to fix it. It’s symbolic. And sometimes it’s hard for a party that prides itself on anti-virtue signalling to make peace with the fact that symbolism is sometimes important.

Hilma’s Network launched in September and more than 550 women have subscribed. Already hosting events in NSW every second month, designed with female non-members in mind, this year we have expanded to Queensland, South Australia and Victoria.

The wheels are in motion within the Liberal Party. The members that love it the most will allow it to evolve. But I don’t think it’s fair to punish a premier with a proven history of supporting women in his state through policy, for the faux pas of party members.

I believe Perrottet would be even bolder in a new term. I believe he will think creatively and enthusiastically about policy that supports women and the environment while also uniting a polarised society.

Plus, he will be the man to get a vibrant Sydney nightlife back and drumming. God knows we need it.

Disclosure: Charlotte Mortlock is an adviser on pacific and international development for Michael McCormack, member for Riverina.

Are the Liberals doing enough to earn your vote? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

There have been plenty of workplace disputes over whether a boss can fire someone for not getting vaccinated — but can you be fired for getting it?

The Church of Ubuntu describes itself as a “non-dualistic all embracing multi-faith philosophy and way of life”.

“We focus,” the church promises, “on total holistic health and well-being, using natural plant-based healing methods.” Naturally, the background of its website is a picture of a gleaming sky through a leafy forest canopy.

The church and “wellness centre” attached is at the centre of another employment dispute around vaccination, and it’s a doozy.

There have been several cases testing whether an employee can be sacked for refusing to be vaccinated. Now a Byron Bay woman is arguing in the Fair Work Commission that she was sacked because she did get the vaccine.

According to the commission’s summary of the case, Ubuntu’s beliefs “include that receiving a COVID-19 ‘inoculation’ is contrary to God’s teachings and the appellant indicated they will not hire anyone as a contractor or volunteer who has received an injection of any of the current or future planned injections purported to protect against the COVID-19 virus”.

We are not at the stage where an employer’s right to do this is being tested — at this point the case has been delayed by Ubuntu arguing that the woman is a contractor, not an employee, and therefore without recourse to unfair dismissal — a pretty conventional workplace response to an unfair dismissal claim.

Fair Work deputy president Ingrid Asbury found in November that the woman was an employee, and on Monday the commission denied the church’s ability to appeal.

It’s not quite a blanket rule that employers — apart from certain industries — can require their employees to be vaccinated. Individual workers have won unfair dismissal cases against employers that sacked them for failing to get vaccinated based on unfair processes. We’ll be keeping a close eye on this one.

‘It tells the story that we’re not good enough’: why isn’t an Indigenous creative agency selling the Voice?

A non-Indigenous ad agency got the contract for the Yes campaign. Indigenous creatives say this misses the point of an Indigenous voice.

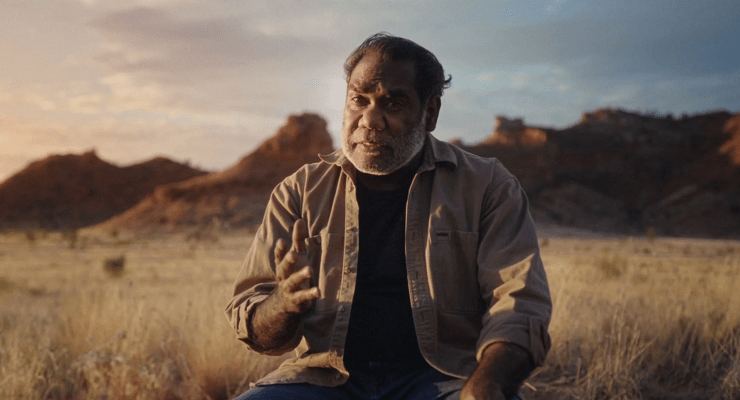

“Why was a non-Indigenous agency hired to do potentially the most important job in history for our people?” said Peter Kirk, co-founder of Indigenous creative agency Campfire X.

“If it’s not Indigenous-led, it’s just another campaign. If it’s not Indigenous-led, it tells the story that we’re not good enough.”

In September, ad agency The Monkeys — on behalf of the Uluru Dialogue Group — pioneered the push for a Yes vote in the referendum on a Voice to Parliament. The campaign was called “History is Calling” and pitched a case for constitutional recognition of First Nations peoples to the Australian public.

The campaign was commissioned by the very group that called for an Indigenous Voice (together with Makarrata to open the door to treaty and truth-telling) in the 2017 Uluru Statement From the Heart. The messaging has come from it, but Kirk said that without Indigenous people on the front foot of the creative process, the campaign comes from the wrong place.

“It’s an Indigenous referendum,” he told Crikey. “It’s about Indigenous people having a voice. It’s about telling Australia that Aboriginal people are good enough to have a voice. And what they’ve done is send a message that Aboriginal people are not good enough.

“Now when they reach out to mob, the first question they’ll be asked is ‘Who worked on it, brother? Who worked on it, sister? ’”

Sydney- and Melbourne-based advertising firm The Monkeys was the agency responsible for the ad and did not respond to a request for comment on First Nations involvement in the creative process by deadline.

Arrernte and Kalkadoon man and award-winning cinematographer Tyson Perkins was part of the ad’s production and said the filming side of things was handled with integrity and a high level of Aboriginal representation.

“Obviously on shows like Mystery Road we’ve had more Aboriginal cast and crew and creatives, but for an ad, it was definitely the highest level of Aboriginal participation that I have experienced on set,” he said.

As well as Perkins, the spot was directed by Kamilaroi man Jordan Watton and composed by Yuwaalaraay man James Henry, and many of the cast were Indigenous. Perkins was clear that his role was rooted in production and he could not speak to the “nuts and bolts of the creative process behind the idea development”.

CEO of First Nations Media Australia Shane Hearn said it was critical for the creative industry to understand that Aboriginal content must involve Aboriginal people from idea inception to campaign creation.

“The whole thing is the voice,” he said. “The Aboriginal songline needs to go from start to finish. It’s not good enough just to have input or output, we need to be part of the horizontal and vertical of things.

“To my knowledge, none of us saw a brief, none of us were invited, it didn’t go through a formal process. Why not? We as a collection of professionals have lots to offer the creative industry.”

Hearn said the lack of due process was symptomatic of an industry that is “a siren of white privilege” and heavily insulated from the realities of Aboriginal Australia. Despite a dire need for diversification and due diligence, he maintained advertising was the correct medium to communicate the ins and outs of the Voice to Parliament.

The government is gearing up for a big neutral (neither Yes nor No) educational campaign on the Voice. Led by the Australian Electoral Commission, it will tap into primarily procedural politics — how to vote and what to look out for.

To vote in the referendum you must be enrolled. And that is where Leigh Harris, creative director of Cairns Indigenous agency Ingeous Studios, said the campaign really fell flat.

As of June 2022, 81.2% of the Indigenous voting age population were enrolled to vote, up from 79.3% in June 2021 and 78% in June 2020. Compare that with the 97.1% (up from 96.2% and before that 96.5%) June 2022, 2021 and 2020 enrolment rates for all eligible Australian voters.

“You’ve got this big thing at the moment but they should have been running the campaign long ago to get blackfellas to enrol to vote,” Harris said. “As an Aboriginal man, I’m a bit bewildered by all of it.”

Crikey contacted the Uluru Dialogue but did not hear back by deadline.

Climate Minister Chris Bowen is facing a barrage of pushback over the crowning jewel of the Albanese government's climate policy.

The Albanese government could be planning to offload billions of dollars’ worth of its own carbon credits to big polluters as the Greens’ extraordinary broadside threatens to derail Labor’s key climate policy, climate analysts have said.

The draft safeguard mechanism legislation, which will almost certainly need the support of all 12 Greens senators to pass, outlines Labor reforms to a Morrison-era policy that would require the 215 big emitters to keep their emissions below 5% a year, or face a hefty fine.

But the Greens have taken issue with a caveat that allows businesses to purchase an infinite amount of Australian carbon credit units (ACCUs) to offset their emissions, which could mean business as usual for the dirtiest corporations in Australia.

The bill also includes lines that outline the government’s intention to offload its own ACCUs as a “cost containment measure to prevent excessive prices”, and energy and climate analyst Michael Mazengarb said the total take for the government could total billions.

“If the new Labor government decides to sell these ACCUs to major emitters at $75 each — as it is suggesting it might do — it will provide a huge windfall profit for the government,” he told Crikey.

Climate and Energy Minister Chris Bowen’s office told Crikey the government was looking at selling only ACCUs it collected after January 11 2023, and that units that had been delivered to the government in the past “would not be sold” under the draft changes.

Even so, Mazengarb said, the government holds contracts to buy 217 million units in total, according to the Clean Energy Regulator, a “decent potential future stream of ACCUs that they could still tap”.

“So there’s still the potential for the government to raise billions in additional revenue should ACCU prices rise in the future,” he said.

But Climate Energy Finance director Tim Buckley said Labor parting with ACCUs was not necessarily a bad thing. Bowen was taking a classic “carrot-and-stick approach” to get industry over the line, he said, “particularly the fossil fuel export sector that is half the safeguard mechanism’s 215 facilities”.

“It is not about getting the teals and Greens onside, it is about bringing along industry and creating jobs so middle Australia, which is currently being smashed by the fossil fuel hyperinflation and cost of living impacts, supports the new government so we can get it embedded by an act of Parliament, and the ALP secures multiple terms,” he said.

However, without the Greens’ support, the safeguard mechanism reforms could be dead in the water. At the recent Smart Energy Council, fired-up Greens Leader Adam Bandt slammed Labor’s “reheating of the Liberals’ climate policy” as 57% of the emissions covered in the mechanism were coal, oil and gas facilities.

All “big corporations have to do is buy a few tree-planting permits”, Bandt said, which he declared was “greenwashing of the highest order” — echoing UN top climate scientist Bill Hare’s words last year that Australia risked becoming “a state sponsoring greenwashing” by allowing offsets without strict parameters.

It follows former chief scientist Ian Chubb’s warning that polluters must make deep cuts in their emissions rather than relying on the get-out-of-jail-free offsets.

But Buckley said the safeguard mechanism — despite its criticism — was a crucial initiative that can get Australia a price on carbon emissions, “which was next to impossible in light of the toxic political agenda that has been running over the last decade”.

“I think it is excellent that Bowen managed to shift the discussion on carbon pricing overnight by talking about a A$75/t cap (indexed at CPI+2% pa). That is double our current level, and changes the narrative brilliantly.”

So where would the money go? Bowen’s office said somewhat cryptically that “any funds from their sale would fund further emissions reductions and support industry decarbonisation via the Powering the Regions Fund”.

Taxpayers deserve more information, Mazengarb said, considering the legislation is the government’s crowning jewel in its climate action reform.

“Given the safeguard mechanism is one of the key pillars of Labor’s plan to reach their 2030 target, the government should outline what investments it intends to make to ensure Australia actually achieves rapid and meaningful reductions in emissions,” he said.

Homework normalises a lack of boundaries between working and personal lives, and burdens teachers with extra duties and unpaid overtime.

Irish President Michael D Higgins made global headlines last week by calling for a ban on homework, arguing students would benefit more from spending their after-school hours developing friendships and playing.

“It should get finished at school [and] people should be able to use their time for other creative things,” Higgins told Irish radio station RTE. However, Higgins doesn’t have the power to change Ireland’s education policies, and Education Minister Norma Foley has vowed to leave the decision up to principals.

As most Australian students return to school this week, it’s high time for a debate about the merits of homework. Should Australia consign it to the proverbial dog’s bowl for good?

Homework gets a D-

There is little correlation between global test scores and the time students spend studying at home. Fifteen-year-old students from Shanghai (who do a whopping 14 hours of homework a week on average) and Singapore (seven hours) score higher than Australia (six hours, one more than the OECD average) on tests by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). But so do Finnish students, who spend fewer than three hours on homework each week.

This is because the educational benefits of homework are small, according to academic studies, and only kick in once students hit their mid-teens.

Australian academics Richard Walker and Mike Horsley, authors of the book Reforming Homework, conclude: “Homework has no benefit for children in the early years of primary school, negligible benefits for children in the later years of primary school, weak benefits for junior high school students and reasonable benefits for senior high school students.”

Why? Recent UK research suggests younger children are often “[unable] to complete this homework without the support provided by teachers and the school”.

Even for older students, only a small amount of homework is beneficial. The OECD surmises that “after around four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested … has a negligible impact on performance”.

Relying on work outside the classroom also exacerbates educational inequality, as students from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to receive help from family members who may be out working or busy with caring responsibilities. Just like increasing private and public school fees, homework shunts more of the burden of education on to individual families, leaving children more reliant on their parents’ resources.

Long hours on the tools crayons

There is also a broader question: why, when we (theoretically) limit the adult work week to 38 hours, do we think it’s acceptable for kids to work 41 hours a week on average (35 hours in school, six hours of homework)? When adults work such hours, they’re usually meant to be paid overtime (again, theoretically).

Homework normalises a culture of working late hours into the night, which conditions students to expect an unhealthy lack of boundaries in their working lives. Spending time with family and friends, keeping active and exploring hobbies and creative pursuits are relegated to afterthoughts. This is especially the case for high-achieving students, who often move into professions with toxic overworking cultures such as medicine, law, finance and consulting, which they’ve been conditioned to accept.

It’s one reason we’ve seen the rising acceptance of unpaid overtime in the Australian economy, particularly among young workers. The average Australian works six weeks’ worth of unpaid overtime a year, losing more than $8000 they’re rightfully owed, according to a November report by the Centre for Future Work. Young people work the most unpaid overtime.

Even if you think the link between homework and overwork is a long bow, it’s clearly a short one for teachers. Teachers rarely have enough time to properly mark homework and provide feedback. It’s thus unsurprising they work 15 hours of unpaid overtime on average a week, according to a 2021 union survey — more than double the national average. Much of it is spent marking homework.

Teacher, leave those kids alone

As our work and home lives have become increasingly blurred through the pandemic, establishing a healthy work-life balance is an important standard to impart to kids from a young age. It will ready them for their economic futures, in which work emails will haunt them digitally if they don’t set strong boundaries.

We should start by heeding Higgins’ call and resigning homework to the history books, at least for primary school students. For older students, we should cap their expected hours at 38, in line with the adult work week. They’re in school for roughly 35 hours a week, and three hours a week of homework fits within the amount the OECD deems beneficial.

It might offend “old school” teachers and parents, but as any teacher marking papers will tell you: for a persuasive conclusion, you must follow the latest evidence.

Homework: who needs it? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.